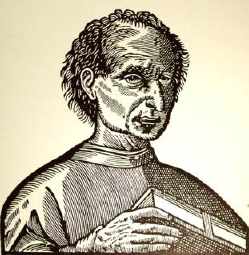

Machiavelli: monster or mastermind?

Controversy and sensationalism have followed Machiavelli from his day to ours. His approach to the art of government, treating politics as a subject beyond the constraints of conventional morality, has caused his name (unjustly) to become synonymous with unprincipled methods of wielding power.

Machiavelli wrote his two major treatises, The Prince and the Discourses, in an attempt to gain favour by a demonstration of political experience and know-how. In The Prince, Machiavelli sets out "to represent things as they are in real truth, rather than as they are imagined".

Machiavelli made a sharp break with traditional literature of the "Mirror of Princes*," which dealt with moral rather than practical issues; he is accordingly considered a forerunner of modern political theory.

Yet, rather than supporting the indiscriminate cruelty and deceit of rulers, Machiavelli viewed political stability as a ruler's foremost consideration, believing that with this end in mind a prince must be capable of being cruel, deceitful, generous or honest as need requires. (See the quotations, both from Shakespeare and Machiavelli, on the next page.)

That strumpet Fortune

Machiavelli gives a fine example of the Renaissance habit of thought by symbol, or icon, as well as offering an uncomfortable insight into attitudes towards women:

As fortune is changeable whereas men are obstinate in their ways, men prosper so long as fortune and policy are in accord, and when there is a clash they fail. I hold strongly to this: that it is better to be impetuous than circumspect; because fortune is a woman and if she is to be submissive it is necessary to beat and coerce her. . . . Always, being a woman, she favours young men, because they are less circumspect and more ardent, and because they command her with great audacity.

(From The Prince. 1961. Trans. George Bull. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1986. See pp. 35, 90, 135.)

Nicolo Machiavelli's The Prince (translated by W. K. Marriott) is on line.

Footnotes

-

Two examples

An example is the medieval political writer, John of Salisbury; closer to Shakespeare's time was the popular Mirror for Magistrates.