Shakespeare's sources in the Histories

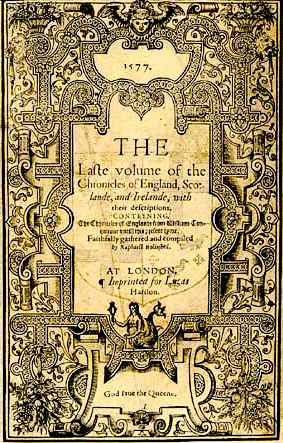

Shakespeare was an omnivorous reader. Often he used several versions of a story in his plots; it seems likely, for example, that before writing Richard III he had read Sir Thomas More's Life of Richard III, and Edward Halle's chronicle The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Famelies of Lancastre and York (1548), as well as one of his most trusted sources*, Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles of England Scotland, and Ireland (1587).

Shakespeare knew his history well, but often he changed the simple facts to suit the medium of the play: time is condensed, battles are combined, characters and actions are modified or created*. Falstaff was not a historical character; Hotspur was really much older than he is portrayed; and characters like Richard III and Joan of Arc bear little resemblance to the figures in modern history books.

More than just a pretty plot

Shakespeare borrowed more than the plot from Holinshed: sometimes he used the actual words--dialogue, description or image. A comparison:

Holinshed

The proclamation ended, another herald cried: "Behold here Henry of Lancaster Duke of Hereford, appellant, which is entered into the lists royal to do his devoir against Thomas Mowbray Duke of Norfolk, defendant, upon pain to be found false and recreant!"

(Holinshed 72)

Shakespeare

Harry of Hereford, Lancaster, and Derby,

Stands here for God, his sovereign, and himself,

On pain to be found false and recreant,

To prove the Duke of Norfolk, Thomas Mowbray,

A traitor to his God, his king, and him,

And dares him to set forward to the fight.

(Richard II 1.3.104-9)

(Click for a clue for a character*)

Footnotes

-

Legendary kings

As well as using Holinshed as a source for his major history plays, Shakespeare took major parts of the plots of Macbeth, King Lear, and Cymbeline from him.

(Click for more on these more legendary kings.)

Holinshed is available in a number of modern editions. That used here is edited by Richard Hosley (New York: G. P. Putnam and Sons, 1968). Some of his works are now available on-line, including fine images from the University of Pennsylvania.

-

Shakespeare's changes

For example, Holinshed attributes the freeing of the captured Douglas to Henry IV, whereas Shakespeare gives the action to Hal, to demonstrate his newly acquired chivalric courtesy (Henry IV, Part One, 5.4.17-33).

-

Signs and portents

In this year [1399], in a manner throughout the realm of England, old bay trees withered and, afterward, contrary to all men's thinking, grew green again: a strange sight, and supposed to import some unknown event

(Holinshed 75).

Shakespeare uses Holinshed's description to develop the character of a superstitious Welsh Captain:

Captain: 'Tis thought the king is dead: we will not

stay.

The bay trees in our country are all withered,

And meteors fright the fixed stars of heaven,

The palefaced moon looks bloody on the earth,

And lean-looked prophets whisper fearful change. . . .

These signs forerun the death or fall of kings."

(Richard II, 2.4.7-11,15)