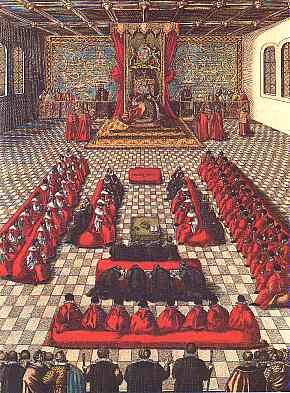

Parliament

Elizabeth's Parliament was summoned when she needed to give popular legitimacy to controversial policies (the Acts of Supremacy and Uniformity, for example), to change or create laws*, or to raise additional direct taxes.

Most governing was done without Parliament; even when it was in session the monarch controlled issues under debate, vetoed any undesirable bills, and dissolved Parliament at will. Occasional challenges to royal prerogative were dealt with smoothly by Elizabeth by temporary imprisonment, reproving speeches, and minor concessions; but the Commons managed nonetheless to secure for itself certain privileges, the most important of which was freedom of speech (though the Queen still decided what matters could be freely discussed).

Elections

Parliament was respected* by most Elizabethans, and considered the highest governing body of the land, uniting the monarch, nobles, and commons in a single "body politic." Of course, it was still assumed that unity of the body politic depended upon carrying out the policies of the monarch, whose will alone was the supreme source of all justice.

The two Houses of Parliament represented the upper nobility, or peerage* (the House of Lords) and the gentry (the House of Commons). They were summoned only at the will of the monarch, who sent writs to nobles and Sheriffs; the latter then notified gentry, yeomanry and burgesses, who assembled to elect two representatives for each shire.

Bills were presented three times for debate before each House, both of which had to assent to the bill in order for it to be passed (always subject to royal veto). Privy Councillors carried great influence, and it was generally known that opponents of royal policy were less likely to receive all-important royal patronage.

Footnotes

-

Law-making

Elizabeth mainly used Royal proclamations to make laws and restrict abuses, but James's abuse of proclamations led the Commons to establish that they were not equal in force to Acts of Parliament.

-

A respected parliament

The respect was on the whole deserved, considering the outright despotism of most European governments in the 16th century; England's representative parliament was unique, despite being limited in power and unrepresentative of the lowest classes.

-

The House of Lords

The House of Lords evolved from the medieval Great Council of magnates, one of which forced King John to sign Magna Carta.