Shakespeare in South Africa: Shakespeare in the Republic

Shakespeare in South Africa -- page 4

Apartheid ascendancy: Shakespeare in the Nationalist Republic

Shakespeare in the Nationalist Republic

South Africa was declared a republic by the apartheid regime in 1960. In 1963, the National Theatre Organisation was supplanted by four Performing Arts Councils (South Africa in those days had only four provinces), and while the move did little to quiet the endemic criticism of state-sponsored theatre - not least from those who were excluded from either experiencing or participating in it on arbitrary grounds of race - it has to be said that some of the productions that resulted were rather fine. Shakespeare, however, was not as conspicuous as one might anticipate. In the first four years of the Arts Councils, CAPAB, the Arts Council for the Cape Province, produced one Shakespeare - an Afrikaans production of Richard III - out of 69 productions; the Natal Council (NAPAC) staged 5 Shakespeares in English out of 40 productions - Natal was a more "English" province, in apartheid terms; the Orange Free State did six Shakespeares out of 35 productions (interestingly, the six came from only 18 English productions); and PACT in the Transvaal produced only four Shakespeare-related productions out of 63, just one of which was a straight production in English (see Performing Arts . . .). Certainly, in terms of frequency of production, Shakespeare was not disproportionately represented.

The effect of the arts councils on Shakespearean production was on the whole to shift it more firmly into the hands of the professionals. The trend can be illustrated in the performance record of one of South Africa's better-known amateur theatre groups. The Johannesburg Repertory Players (the "Jo'burg Reps") were formed in 1928 under the Chairmanship of the redoubtable Muriel Alexander, opening with a season of two plays that same year at the Standard Theatre, Karel Kapek's R.U.R. and a modern dress Merchant of Venice. Anticipating late-twentieth century school Shakespeare pedagogies by some years, the Shakespeare "event" issued its own newspaper, The Gondola Express, whose headlines shouted: Sensational Development in Big Trial! Melodrama in Real Life. Antonio acquitted. Shock for Shylock! The choice of modern dress arose because "the society could not afford the rich costume of the period" (Hoffman 22).

The Shakespeare productions by the Performing Arts Councils in the 70s and 80s were a mixed bag, sometimes striving for Grand Theatre, often aping Stratford (the Brook Midsummer Night's Dream was as influential in South Africa as anywhere), and occasionally they were remarkably good. There were also some lively Afrikaans productions, such as Ilse van Hemert's Die Sakeman van Venesi' (The Merchant of Venice) for PACT at the State Theatre in 1991. It might be fair to say that apartheid theatre never reached the heights achieved by the ballet and classical music.

Open-air Shakespeare

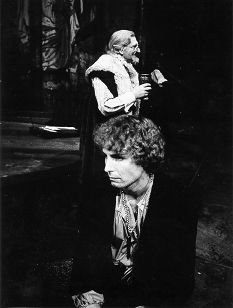

A photograph from the first production at the Maynardville Open-air Theatre in 1956,

a production of The Taming of the Shrew with Leslie French, Dick Leftwitch and Cecilia Sonnenburg.

Click on the image to see a larger version, and use the "back" button on your browser

to return to this page.

While this professionalisation was in progress, Shakespeare gained a new foothold in semi-professional production with the creation in 1956 of the Maynardville Open Air Theatre in Wynberg, a suburb of Cape Town. This was again the brain-child of two women, René Ahrenson and Cecilia Sonenburg, who inveigled the British actor-producer Leslie French, famous for his roles as Puck and Ariel at the open-air theatre in Regents Park, London, into directing an annual Shakespeare production, which he did for a number of years despite the growing pressures of the cultural boycott. The tradition survives as an enjoyable part of Cape Town's annual cultural calendar. In 2000 Clare Stopford's production of Romeo and Juliet, featuring the gang-ravaged youth culture of the Cape Flats, its premise the divided city of Cape Town, took Maynardville by storm. 2002 saw Fred Abrahamse's 60s "summer of love" production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, with youngsters standing up against the repressive laws of Athens - music by Carl Johan Lingenfelder and a soundscape designed by Dave Cathcart.

Leslie French also made an important contribution to the design of South Africa's second open-air Shakespeare theatre, Mannville in Port Elizabeth, established by husband-and-wife team Bruce and Helen Mann (see Mann and Wright: 2001). Like Maynardville, the Port Elizabeth Shakespearean Festival, formed in 1970, produces an annual open-air Shakespeare, often a current school set-work. Even through the worst travesties of apartheid, audiences of all races attended these Port Elizabeth shows together. The 30th anniversary production of The Taming of the Shrew took place in February 2002, with Kate looking like Annie Oakley and shooting pistols all over the place.

The Annual Grahamstown National Arts Festival, which grew out of a local tradition of commemorating the British Settlers of 1820, had a brief for Shakespeare. In its early years there was very often a major Shakespearean production. Among the more impressive of these were the CAPAB Lear presented during the 1974 festival inaugurating the 1820 Settlers National Monument, directed by Roy Sargeant with Michael Atkinson as Lear; and latterly PACT's 1990 Richard II, directed by Keith Grenville, with Neil McCarthy in the title role and wonderful designs by Peter Cazalet.

The Shakespeare Society of Southern Africa grew out of the Festival. Its formation was suggested by Johannesburg journalist Joe Podbrey, in discussion following a Winter School lecture by Muriel Bradbrook during the Shakespeare Festival of 1984. The Society was inaugurated at the Festival the following year, with the late Guy Butler as President, and currently has small branches in many of the major centres. The society's annual journal, Shakespeare in Southern Africa, has been published since 1987, and the organisation holds a Triennial Congress (see http://ru.ac.za/shakespeare ).

As apartheid crumbles

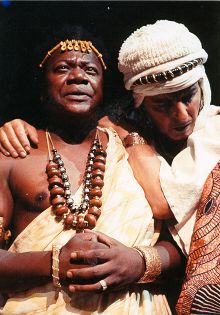

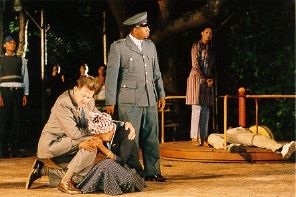

Shakespearean visits from the metropolis never recovered from the cultural boycott of the 80s and 90s. South Africa is no longer self-evidently a parade ground for British theatrical culture. Both economics and, to a lesser extent, ideology are against it. The RSC has steered clear, but there have been occasional expatriate forays such as Janet Suzman's 1997 production of Othello at the Market Theatre, starring John Kani in the title role and the late Richard Haines as Iago. Kani took some bad press for seeming a bit swamped in the role, being unintelligible at times and forgetting his lines. Haines tended to overplay. But the production overall was powerful in conception, clean, and made its cultural and racial point without resorting to strident signposting. The evidence is there in the film record of the production. Then came Antony Sher's Titus. The production was huge when it toured afterwards in Britain. At the Market Theatre it rather flopped, not least because Sher relied on a foreign cast to play clumsy stereotyped Afrikaners. This didn't really work. Sher was deeply wounded, and assumed that the reaction was the result of his leading role in galvanizing the cultural boycott. Doubtful, but the lesson perhaps was that exile is a state of mind not easily relinquished. He has written in detail about the whole experience (Sher and Doran 1996; Sher 2001).

The post-1994 dissolution of the performing arts councils had the unintended consequence of liberating Shakespeare from the shadow of "state culture." The money drained away, but so did the alarming portentousness that had come to be associated with some of them. Ensemble theatre productions by "scratch" companies became more numerous, many of them premiering at the Grahamstown National Arts Festival. Among the best of these was a startlingly good King Lear directed by James Whylie in 1998 for the "Takeaway Theatre Company," with Sean Taylor as Lear. Their next effort, Antony and Cleopatra, the following year, was more pedestrian: the chemistry between the two leads just wasn't there.

From Yael Farber's production SeZaR, with the slain Sezar (Hope Sprinter Sekgobela), Brutas (Menzi 'Ngubs' Ngubane) and

Sinna (Siyabonga Twala). (Photo Ruphin Coudyzer)

Shakespeare seems set to retain a small place on South African stages, mercifully without the ignominious validation thrust upon him by colonialism. He survives, not through any mysterious political conspiracy, but because of his power in the theatre. South Africa's Shakespearean standard for the new millennium has been pegged by Yael Farber's SeZaR, based partly on Sol Plaatje's 1937 Tswana translation of Julius Caesar (Dintshontsho tsa bo-Juliuse Kesara), partly on Shakespeare's English text, and with workshopped contributions from the Zulu, Pedi and Tswana-speaking cast. The production premiered at the 2001 National Arts Festival in Grahamstown, and went on to earn plaudits in Cape Town and Johannesburg as well as at the Oxford Playhouse and Winchester in the United Kingdom. Wholly about Africa, and thoroughly controversial, this was a confidently post-colonial Shakespeare (see Wright 2001).