The printing press

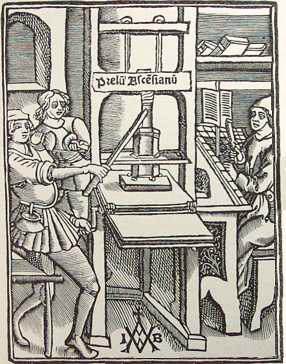

The main processes in printing a book involved setting the type, (the compositor in the background), printing (including proof-reading) and binding.

Click to read about each of the steps in the printing process:

The next step: selling the book

Most books were sold by the printers or the stationers who commissioned the printing of a book. In London, the great centre of the book trade was the yard of Saint Paul's Church. Stationers also travelled around the country, selling their books at the major country fairs. Occasionally they would travel as far afield as the great book fair at Frankfurt (still held annually).

Often, to save the cost of binding, books were sold simply as sheets stitched together--probably such sheets are stored in the bins at the left in the illustration.

Footnotes

-

The compositor

The compositor sat in front of two cases, one, the upper, with capital letters, and the other with what we still call "lower-case" letters (and ligatures--letters that were cast as a pair, like "Æ" in this computer font). He would slot the letters, upside down, into a composing stick that would hold a line of text. The finished line was added to others in a "galley" until a page was finished. This block of type would then be placed on a table to go with the other pages.

Two, four, or more pages, depending on the size of the planned book, were set in a "forme," then printed on one side of a sheet of paper. A full sheet, however many pages, would then be printed. When a book was finished the type was broken up, resorted, and reused.

-

Printing

Printing was a fairly simple process: the type was locked firmly in the forme, and a sheet of paper (slightly moist, to hold the ink better) was fitted onto the tympan, which protected the edges of the paper from inking; the frisket, which took the weight of the press, was then lowered onto it.

The type was inked (the man on the left in the graphic holds the inking pads), the frisket was swung flat, onto the type, and the whole arrangement was slid under the platen--the upper metal part of the press--which was pressed firmly onto it with the help of the screw so that a good impression would be made on the paper.

The completed sheet of paper would be hung briefly to dry, then stacked either for the second side to be printed, or for binding.

-

Stop the presses!

The first sheet would be taken to the proof-reader, but usually the press would continue with the uncorrected type until the proofreader had finished--after all the pressmen would otherwise have to sit idle. The result was that some uncorrected sheets would find their way into the book being printed.

When the proof-reader had finished, the press was stopped, the corrections made, and the press run continued.

It was rare indeed for an author to be on hand to assist in proof-reading. Shakespeare may have proofed his long poems, but he certainly had no hand in printing or proof-reading his plays.

-

The finished product

Finally, the sheets of printed material were taken to the binder, where they were collated, folded, sewn, bound, and the edges trimmed so that the folded pages were cut. The book was then ready for the bookseller.