Myth: new subjects to conquer

As the humanists rediscovered the riches of classical literature, they found in Greek and Roman myth a rich source of evocative narratives.

At first the myths were allegorized in order to fit them into a Christian framework*; in due course the habit of allegory meant that classical myth permeated even the world of politics, where Queen Elizabeth exploited the myth of Diana, Goddess of hunting and chastity, as part of her cult of the Virgin Queen.

Shakespeare's use of mythology

By the time Shakespeare was writing, he was able to capitalize on the often frank sensuality of classical myth in such works as his narrative poem Venus and Adonis. The myth of Venus and Adonis is discussed elsewhere, both in the discussion of the period of Shakespeare's life when he wrote the poem and in the art of the Renaissance.

Though only one of his plays could be said to be based on a classical myth (Troilus and Cressida, a bitter debunking of the Trojan saga), Shakespeare often uses myth as part of the network of references that creates the web of meaning in his plays. One of many examples is the connection he makes in Antony and Cleopatra between Hercules, Mars, and Antony; and between Venus and Cleopatra.

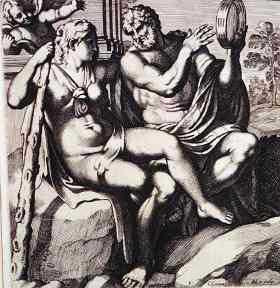

The illustration here is of Hercules and Deianeira, a myth* that is referred to in Antony and Cleopatra at the moment when Antony believes that he has been betrayed by Cleopatra (Alcides is another name for Hercules):

Antony: The shirt of Nessus is upon me. Teach me, Alcides, thou mine ancestor, thy rage. Let me lodge Lichas on the horns o' the moon, And with those hands, that grasped the heaviest club, Subdue my worthiest self.

(4.12.44-47)

Footnotes

-

Weaving stories

Writers like Edmund Spenser combined in a multi-layered allegorical tapestry the myths of Greece and Rome, the romances of medieval knights and maidens, and the stories and teachings of the Bible and the Christian saints.

-

Hercules and Deianeira

On one occasion as [Hercules] was travelling with his wife [Deianeira], they came to a river, across which the Centaur Nessus carried travellers for a stated fee. Hercules himself forded the river, but gave Deianeira to Nessus to be carried across. Nessus attempted to run away with her, but Hercules heard her cries and shot an arrow into the heart of Nessus. The dying Centaur told Deianira to take a portion of his blood and keep it, as it might be used as a charm to preserve the love of her husband.

Deianeira did so, and before long fancied she had occasion to use it. Hercules in one of his conquests had taken prisoner a fair maiden, named Iole, of whom he seemed more fond than Deianeira approved. When Hercules was about to offer sacrifices to the gods in honour of his victory, he sent to his wife for a white robe to use on the occasion. Deianeira , thinking it a good opportunity to try her love-spell, steeped the garment in the blood of Nessus. We are to suppose she took care to wash out all traces of it, but the magic power remained, and as soon as the garment became warm on the body of Hercules the poison penetrated into all his limbs and caused him the most intense agony. In his frenzy he seized Lichas, who had brought him the fatal robe, and hurled him into the sea. He wrenched off the garment, but it stuck to his flesh, and with it he tore away whole pieces of his body. In this state he embarked on board a ship and was conveyed home.

Deianeira , on seeing what she had unwittingly done, hung herself. Hercules, prepared to die, ascended Mount OEta, where he built a funeral pile of trees, gave his bow and arrows to Philoctetes, and laid himself down on the pile, his head resting on his club, and his lion's skin spread over him. With a countenance as serene as if he were taking his place at a festal board he commanded Philoctetes to apply the torch. The flames spread apace and soon invested the whole mass.

From Bullfinch's Mythology (1855).