Mandragora: magic or botany?

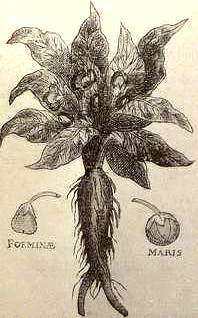

Images of the mandrake root, on the left from a medieval herbal, on the right from Gerarde's Herbal (1597).

The mandrake, with its branching roots, was thought to resemble a human figure, and to scream* when it was uprooted. Since the plant does contain a natural narcotic, it attracted much superstition*. The difference between the medieval and Renaissance illustrations here shows how the artist's eye learned to look at what was really there*, not what was said to be there by earlier writers.

Footnotes

-

A mandrake's best friend

The scream was so intense that it could kill those who heard it. The proper technique was to tie a dog to the plant (preferably at night, when the plant's powers were at their height), then call the dog from a distance, thus pulling it up.

-

An aphrodisiac

Amongst other things, it was considered to be an aphrodisiac, and to increase fertility: "Take of this herb [wild teasel] and temper it with the juice of mandrake, and give it to a bitch, or other beast, and it shall be great with a young one . . . and it shall bring forth the birth . . . of the which young one, if the tooth be taken and dipped in meat or drink, every one that shall drink thereof shall begin anon battle" (From The Book of Secrets of Albertus Magnus).

-

The mandrake's legs

Though even the Renaissance engraving on the right shows the mandrake with roots that look suggestively like human (if somewhat hairy) legs.

-

Friar Lawrence on herbs

One of Shakespeare's specialists on herbs is Friar Lawrence, in Romeo and Juliet. In the early hours of the morning after the Capulets' masque, he appears with a basket, collecting herbs and commenting on their potential for good or evil:

O mickle [much] is the powerful grace that lies

In plants, herbs, stones, and their true qualities;

For naught so vile that on the earth doth live

But to the earth some special good doth give;

Nor aught so good but, strained [forced] from that fair use,

Revolts from true birth [nature], stumbling on abuse.

Virtue itself turns vice, being misapplied,

And vice sometime by action dignified.

(2.3.15-22) -

A herbal history

Early herbals were derived from the writings of the Greek Dioscorides, or the Latin encyclopaedist, Pliny. They emphasised the miraculous and strange, and the illustrations were, like the one on the left, unrealistic, and crude. A German artist, in 1530, illustrated a herbal with drawings of beauty and botanical accuracy; it is probable that his work stimulated the surge of fine botanists who followed, in particular the Englishman William Turner, and the Belgian Rembert Dodoens.

Herbal medicine--some probably effective, some not--continued in England well into the eighteenth century, with the works of Nicholas Culpeper (born the year of Shakespeare's death) still being printed today.

Shakespeare was familiar both with the herbals, and with the traditional associations between herbs, medicine, and the seasons; both Ophelia, in Hamlet, and Perdita, in The Winter's Tale, use the language of herbs, Ophelia to blame, Perdita to praise.

Herbs with a message

Though there is some doubt about the exact meaning of the various herbs Ophelia distributes, she suggests that those around her are flatterers and hypocrites, faithless, and short of memory. See 4.5.175-85.