What did Elizabethans consider a crime?

Attitudes towards crime in the Elizabethan and early Stuart period had two distinctive features: an almost paranoid concern for order in society, and a close association between crime and sin*.

The Reformation and the increased power of the puritans changed perceptions of crime and justice both in government and in the popular mind. Religion and morality became matters of state law and potential sources of rebellion; although sin and crime were usually dealt with by different courts (crime by the civil court, sin by the ecclesiastical court), they were in some ways almost indistinguishable.

The belief that all crime was sinful is shown by the almost invariable repentance of criminals on the gallows, warning their fellows not to stray from the path of law and godliness*.

Close to panic?

An atmosphere of uncertainty--at times amounting almost to panic--had been created by religious change, increasing public concern about godly behaviour and the threat of sin to society as a whole. Some believed that the apocalyptic Last Judgement was near at hand, or that all England would suffer divine wrath if sins went unpunished* (perhaps in the same way that England was believed to have been punished for Henry IV's usurpation).

Order and anxiety

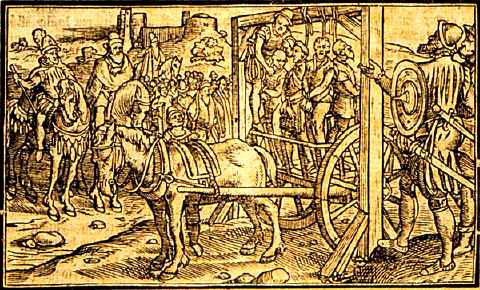

Fear of civil war remained strong long after the Wars of the Roses; there were also threats of religious strife, a Spanish invasion, and a growing number of unemployed poor*. It is not surprising that Elizabethans were unusually concerned with preserving order in their society and that the concept of divine order should be much on their minds. It was preached from the pulpit, and was reflected in the entire approach to crime and justice--even in the informal way that communities maintained order (for the most part without resorting to process of law).

Footnotes

-

Sinful crime, criminal sin

Most sexual offences were handled by the ecclesiastical courts. The major exception was the crime of sodomy, the punishment for which was made more severe immediately after the dissolution of the monasteries, mainly as a means of discrediting the displaced monks. Sodomy was consistently grouped with sorcery and bestiality as a kind of criminal heresy, an offence against the divine and civil order, and was punishable by death, all property of the convicted person to be confiscated.

There are, however, few recorded instances of the law being enforced. It appears (in Hamlet's words) to have been "a custom / More honoured in the breach than the observance" (1.4.15-16).

One of the charges levelled against the theatre by the puritans was that the presence of boys as actors brought the players under suspicion of committing and encouraging "abominations."

-

One sin leads to another . . .

It was a common belief of the criminals themselves, and a typical theme of their repentance, that small sins unchecked always led to greater sins by a process of spreading corruption:

The dram of evil

Doth all the noble substance of a doubt,

To his own scandal.

(Hamlet 1.4.36-38)Compare Hamlet's statement to the following repentence of a prisoner before the gallows:

"The first sin I began with, was sabbath- breaking, thereby I got acquaintance with bad company, and so went to the ale-house, and from the ale-house to the baudy-house: there I was perwaded to rob my master, as also to murder this poor innocent creature, for which I am come to this shameful end"

(the repentance of Thomas Savage on the scaffold, executed in 1668 for killing a fellow servant, quoted in Sharpe, J.A. Crime in Early Modern England, 163). -

The end draweth nigh

In the 1590s, a justice announced that Kent authorities faced "such an inundation of wickedness in this last and worst age that. . .we are justly to fear that we shall every one be overwhelmed thereby."

(Quoted in Sharpe, J.A. Crime in Early Modern England, 159.) -

The threatening poor

Wandering poor were a product of England's rapidly increasing population and extensive land enclosures. Fear of the unemployed poor gave rise to harsh laws against vagrancy, and aroused suspicions of an organized criminal subculture. By the late 16th century the poor were commonly described as a many-headed monster threatening chaos to society.

Shakespeare's Coriolanus calls the people of Rome the "many-headed multitude" (2.3.17-17), and has some harsh things to say to them:

You are no surer, no,

Than is the coal of fire upon the ice,

Or hailstone in the sun. . . your affections are

A sick man's appetite, who desires most that

Which would increase his evil. He that depends

Upon your favours swims with fins of lead

And hews down oaks with rushes. Hang ye! Trust ye?

With every minute you do change a mind. . .

(1.1.174-84)

(Click for the Midlands Rebellion--which may have influenced Shakespeare's attitude.)