Order in the sexes

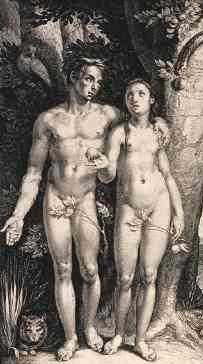

The concept of equality between the sexes would have seemed very foreign to most in Shakespeare's day: Adam was created first, and Eve from his body; she was created specifically to give him comfort, and was to be subordinate to him, to obey him and to accept her lesser status. A dominant woman was unnatural, a symptom of disorder.

The medieval church had inculcated a view of women that was split between the ideal of the Virgin Mary, and her fallible counterpart, Eve, or her anti-type, the Whore of Babylon*. Unfortunately, the Virgin Mary was one of a kind, so there was often a general distrust of women; Renaissance and Medieval literature is often misogynistic.

Queen Elizabeth cultivated the view that she was the ideal; Joan of Arc, on the other hand (at least in Shakespeare's play Henry VI, Part One), was seen as a devil*. (More on "disorderly" forms of sexuality* in the Renaissance.)

The courtly poet Sir Thomas Wyatt dramatized a debate between two pastoral figures on the opposing views of women as ideal and fallible. Click to see--and hear--the debate.

The accepted hierarchy of the sexes was so much taken for granted that it influenced even the literature of farming.

A lesson on domestic order

In The Taming of the Shrew, Kate, tamed, gives a famous (or infamous, or ironical) lesson to the other women on the "natural" domestic order. The imagery makes clear the correspondence between the family and the nation:

Thy husband is thy lord, thy life, thy keeper,

Thy head, thy sovereign . . .

Such duty as the subject owes the prince,

Even such a woman oweth to her husband,

And when she is froward, peevish, sullen, sour,

And not obedient to his honest* will,

What is she but a foul contending rebel

And graceless traitor to her loving lord?

I am ashamed that women are so simple [foolish]

To offer war where they should kneel for peace,

Or seek for rule, supremacy, and sway,

When they are bound to serve, love, and obey.

(5.2.148-66)

The Medieval Feminist Index lists scholarship on women, sexuality, and gender.

Footnotes

-

"The greatest heights and the lowest depths"

The textbook of witch-hunters, the Malleus Maleficarum, includes this passage in explaining why more women than men are witches:

Some learned men propound this reason; that there are three things in nature, the tongue, an ecclesiastic, and a woman, which know no moderation in goodness or vice; and when they exceed the bounds of their condition they reach the greatest heights and the lowest depths of goodness and vice. When they are governed by a good spirit, they are most excellent in virtue; but when they are governed by an evil spirit, they indulge the worst possible vices.

-

Devil or angel?

Jealous men in Shakespeare's plays have difficulty seeing women as something between these two extremes: if they are not perfect they must be whores: thus the abrupt swing between love and hate in such characters as Claudio (Much Ado About Nothing), Othello, Posthumus (Cymbeline), and Leontes (The Winter's Tale).

Hamlet has similar problems with his mother, and advises Ophelia to get to a nunnery to avoid the evils of the world altogether.

-

A loophole?

There is an important distinction here: Kate suggests indirectly that if the husband's will is not "honest" (honourable), then obedience is not required.

-

Disorderly sex?

Most of the documents from the period concerning sexual behaviour that was considered improper deal with adultery and fornication, activities that were dealt with in the ecclesiastical courts. There is little information about other kinds of sexual behaviour. Male homosexual acts were the subject of severe laws, but these laws seem to have been seldom enforced; they were used more as a kind of propaganda to discredit the male priesthood of the dissolved Catholic Church than as a serious method of enforcing the moral norm of heterosexuality. Lesbianism was neither written about nor legislated against.

Despite the laws against homosexual acts, it is probably misleading to think of homosexuals in the period as oppressed, simply because those with different sexual preferences would not have seen themselves as a group, or as having rights. It is nonetheless true that both Marlowe and James I were rumoured to have been involved in homosexual relationships.

Then of course there is the puzzle of Shakespeare's sonnets, and the literary tradition--based on a combination of classical philosophy and Christian misogyny--that put male friendship above any other form of human love. And the ambiguities generated by the presence of boy actors in the theatre.

Classical examples

Plato, followed by Plutarch (whom Shakespeare certainly read), both proclaim that the act of loving boys is superior to loving women because it is less subject to the kind of passion that subdues reason.