- Edition: King John

Performance History

- Introduction

- Texts of this edition

- Contextual materials

-

- Chronicon Anglicanum

-

- Introduction to Holinshed on King John

-

- Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland 1587

-

- Actors' Interpretations of King John

-

- King John: A Burlesque

-

- The Book of Martyrs, Selection (Old Spelling)

-

- The Book of Martyrs, Modern

-

- An Homily Against Disobedience and Willful Rebellion (1571)

-

- Kynge Johann

-

- Regnans in Excelsis: The Bull of Pope Pius V against Elizabeth

-

- Facsimiles

62Herbert Beerbohm Tree's production, 1899

On more conventional stages, King John was performed by Samuel Phelps in the 1860s, and by Osmond Tearle for the first time in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1890. Tearle retained the tradition of historical accuracy; a reviewer from the Birmingham Post commented that Tearle's "Make-up was very correct, being taken from the picture of the King in the National Gallery. Tearle's acting of the scene with Hubert must have been suitably villainous, since it "called forth a burst of applause, in which some hisses were even mingled." The part of King John was not attempted by the later nineteenth century Shakespearean tragedian Henry Irving, though his edition of the plays, printed in collaboration with Frank Marshall, indicates the cuts he might well have used had he chosen to produce the play (the cuts he indicates follow Macready closely). The Introduction to King John in this edition may indicate Irving's reason for not taking on the part, since it suggests that the king is an unsympathetic figure, and the play therefore anticlimactic (3:157). It is also true that Irving did not perform the king in Henry V either; an alternative possibility is that the Victorian pax Britannicamade the need for patriotic English kings less pressing.

63The pinnacle of spectacular nineteenth-century productions of King John was reached at the close of the century--1899--in a production by Herbert Beerbohm Tree. King John had not been performed for thirty years, so Tree's audience would for the most part not have seen the play performed. Tree's production was magnificent, with elaborate scenery, and involved a huge cast in which even the relatively minor nobles presented on stage were adorned with multiple followers, each in their respective livery. Though not quite a cast of thousands, the number involved was, to modern playgoers, no less extraordinary--three hundred and eighty five "supers" in addition to the basic cast of about twenty. Until very recently, editors discussing the performance history of King John have tended to dismiss this production as an example of excessive, even destructive spectacle: "Beerbohm-Tree's fancy staging in . . . in its very excess may have killed the play. By outdoing what had been done in earlier productions, Tree set out to please the eye or amuse the audience at any cost to the drama, no matter how intrusive" (Beaurline 19). James Ellison, writing about the surviving film fragment from Tree's production describes it as belonging to an "extravagant and now outmoded tradition" (294). Extravagant it certainly was, but it is surely inaccurate to describe a penchant for spectacle as outmoded: modern stage technology permits extraordinary spectacle in the staging of musicals (and even sometimes of Shakespeare), though live horses may be a thing of the past. The now-dominant medium of film gains much of its appeal from spectacular on-location shots, and increasingly the excitement of special effects-- we have only to think of recent Shakespeare films from Kenneth Branagh, Baz Luhrmann, and others to realize that love of spectacle has not altogether disappeard from Shakespearean performance.

64It is perhaps unfair to cite Ellison's lapse into a somewhat unquestioning acceptance of earlier critical judgment at this point, for his study of Tree's production is both nuanced and wide-ranging. He builds on the earlier work of Barbara Kachur, who pointed out the importance of contextualizing the production within the politics of the time; King John is, after all, an intensely political play. Kachur explores impact on the production of the looming advent of the second Boer war, seeing Tree as fostering patriotic support for the imperialism that lay behind the war. Ellison complicates this interpretation, pointing out that contemporary reviews saw the play in strikingly varied ways, either as supporting or questioning the government's agenda. In the process, Ellison highlights the "awkward questions and subtexts" of both Shakespeare's text and Tree's staging of it (304). Ellison also demonstrates the importance to the production of the currently sensational Dreyfus affair in France, in which Albert Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army, had been falsely accused of treason. A few months before the first night of Tree's production, the French army has been forced to initiate a second trial, in the light of new evidence, and the whole affair had been the subject of much anti-French comment in England. Thus the play's potentially equivocal patriotic passages, and its portrayal of a central government deeply flawed by corrupt practices, were intensely topical.

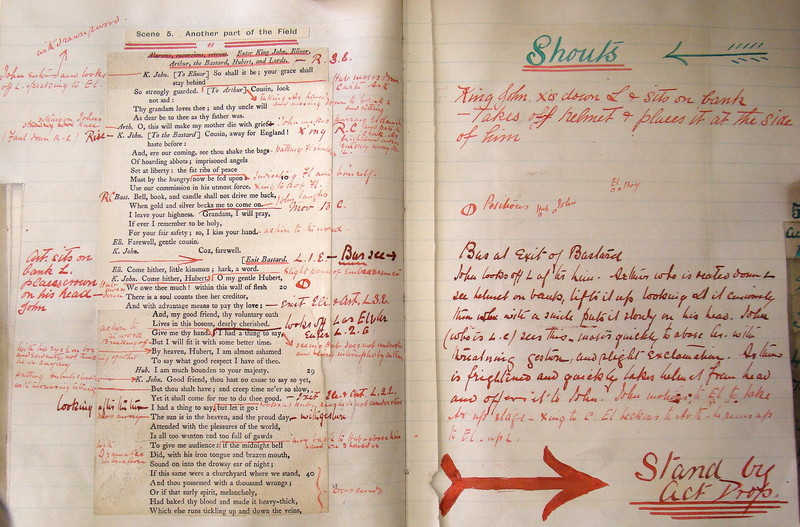

65Contemporary reviews of Tree's King John were kinder than more recent critics. No less a reviewer than George Bernard Shaw devoted two long and laudatory reviews to the production, singling out the interpolated jester, the use of music and chanting, and the stage business his "errant memory" recalled. Tree's King John was certainly inventive in its stage business, as well as spectacular in sets and costumes. Three examples will give a sense of the way his theatrical sense extended the text in a manner that is remarkably like modern film in its use of the visual to explore character, and in many places, a sound track to heighten emotion and to comment on the action. The first example is the much-cited moment in the play when John hints to Hubert his desire that Arthur be killed (3.2, TLN 1259-1370). The staging makes much use of flowers (daisies, apparently) that are part of the set: Arthur innocently picks them; John uses his sword to cut them. Just before this moment there is some business no less symbolic (or melodramatic, perhaps). As the Bastard exits, Arthur is playing with a helmet he finds, putting it on his head. John sees this, moves "quickly to abuse Ar[thur]. with threatning gesture, and slight exclamation." Arthur, frightened, offers the helmet to John.

66Somewhat later in the play, in the scene when John discovers that Arthur has after all not been murdered by Hubert (4.2, TLN 1974-1994), the prompt book first provides a running commentary on John's reaction to Hubert's narrative, then relates the extensive business that follows Hubert's exit. In this transcription, descriptions of action are italicized, while music cues are in roman type.

|

K. John. Out of my sight, and never see me more. My Nobles leave me, and my state is braved, Even at my gates, with ranks of foreign powers; |

[With gesture of dismissal] Clock strikes 10. Distant Chant. Monks enter on platform-- L. & exit into chapel -- C. at back. |

| Nay, in the body of this fleshly land, This kingdom, this confine of blood and breath, Hostility and civil tumult reigns |

[beating his breast] |

| Between my conscience and my cousin's death. | Chant dies away |

|

Hub. Arm you against your other enemies. I'll make a peace between your soul and you. |

|

| Young Arthur is alive. This hand of mine | Chant |

| Is yet a maiden and an innocent hand, Not painted with the crimson spots of blood. Within this bosom never entered yet The dreadful motion of a murderous thought, And you have slandered nature in my form, Which, howsoever rude exteriorly, Is yet the cover of a fairer mind Than to be butcher of an innocent child. |

[John during this speech has at first his head buried in his arms -- then gradually as if expecting something which he fears is too good to be true hysterically rising and throwing himself into Hubert's arms] |

| Young Arthur is alive. | Music -- L. Then dies away |

|

K. John. Doth Arthur live? O, haste thee to the peers, Throw this report on their incensèd rage, And make them tame to their obedience. Forgive the comment that my passion made Upon thy feature, for my rage was blind, And foul imaginary eyes of blood Presented thee more hideous than thou art. O, answer not, but to my closet bring |

[hysterically rising and throwing himself into Hubert's arms] |

| The angry lords with all expedient haste. | Exit Hub. -- R. At back. |

| I conjure thee but slowly: run more fast! | [Calling after him.] |

67The stage business that follows, as the act closes, focuses on John's internal struggle, combining a reminder of his political cunning with a suggestion that the action by Hubert that has (apparently) delivered him from his own villainy is a sign to him that he should renew his faith. In the context of the disappointment that is to follow, the stage business underlines Shakespeare's deeply ironic treatment of this episode, while providing Tree with an opportunity to deepen his characterization of John. On stage as Hubert leaves, John is still holding the warrant for Arthur's death, handed to him earlier by Hubert. The prompt book continues:

68John rushes down stage -- with an hysterical laugh -- then sees document in hand -- and with a cunning look sees brazier and puts warrant on the top -- watches it burn then hears chant -- crosses himself -- face up -- with green focus lime on -- then moves upstage -- faltering -- when in middle of steps with arms up to cross:-- TABLEAU CURTAINS.

69Mention here of the tableau curtains is a reminder of the most controversial of Tree's decisions in staging the play: the addition of two tableaux. The first, of the second battle between the English and French armies outside Angiers, came between Tree's fourth and fifth scenes (in the middle of 3.2 in this edition, TLN 1296), and employed horses as well as a large cast of extras. In the original, the Bastard had just entered with Austria's head; this stage effect, however, must have been considered too gruesome for late nineteenth century sensibilities, so is omitted by Tree. Instead, as the Bastard proclaims "for very little pains / Will bring this labor to an happy end" (TLN 1296-96), Tree's prompt book reads "Exit John . . . Enter Austria & 4 Men-at-arms who attack Bas[tard]. & Hub[ert]." Tableau curtains fall, allowing the cast and horses to assemble on stage. Designed by Joseph Harker, the tableau is reminiscent of the woodcuts illustrating battles that Shakespeare would have found in his edition of Holinshed's Chronicles.

70The second tableau, inserted after Tree's second intermission (between 4.3 and 5.1 in this edition), was a kindly attempt to make Shakespeare more knowledgeable about the important events in the reign of King John: surrounded by his disaffected nobles, the king signs that important document so glaringly ignored by Shakespeare, Magna Charta. The program for the production included a discussion of the importance of Magna Charta, indirectly justifying the inclusion of the tableau:

71The granting of Magna Charta--the most important event in John's reign and one of the most solemn moments in our history--finds no mention in Shakespeare's play. Of course, the Charter was no novelty, nor did it claim to establish any new constitutional principles. But it came at a time when the pressure of the nobles, the despotism of the king, and the power of the clerics threatened to stifle the English constitution. Magna Charta gave back to the people that government of themselves which in a century-and-half of foreign dominion and of foreign wars had been denied, or at least waived aside. (See the full passage.)

72The absence of any mention of the Charter is discussed in the General Introduction [[link to come]].

73Costumes and stage sets were as elaborate as the tableaux. Percy Anderson's costumes, remarkable in their artistic quality, combined historical accuracy with elegance and beauty, and his drawings of major characters are strikingly accurate in catching the faces and figures of the actors who were to play the parts. The collection in the Theatre Collection at the University of Bristol is extensive, with over a hundred and seventy sketches, but it clearly does not, even so, include the whole cast. Nonetheless the collection gives a remarkable sense of the depth of design and complexity of the production: a single noble is accompanied by sketches for a servant, page, knight, and esquire, all part of his retinue; supernumerary characters abound, from the Archbishop of Canterbury to multiple monks; there is even a court jester who was involved in a piece of business that has caught the eyes of earlier writers on the stage history of King John (Beaurline 19, Cousin 45). Bernard Shaw's lengthy review of Tree's production describes some of the jester's actions -- among other things he helps the unattractive Robert Faulconbridge offstage with a blow of his bladder (cited from the transcription in Furness, Variorum; see [[link]]the full review).

74Costumes are carefully designed to emphasize character: the ladies accompanying Eleanor, Constance, and Blanche are all given costumes appropriate to their mistresses; and villains -- Hubert and his two Executioners (Murderers) are suitably dressed in dark, threatening colours.

More important characters had more than one costume: in addition to his initial, suitably royal outfit, John is given a dark, somber dress for his later scene with Pandulph, the Bastard has more than one flamboyant outfit (one is shown here) and Arthur has a second costume for his disguise as he attempts to escape. The sketches provide some hints as to production choices; both Arthur and Prince Henry are portrayed as very youthful -- if anything, Henry appears to be younger than Arthur -- as Tree picks up on Shakespeare's characterization of both as boys, retiring rather than plunging into the world of war and politics.

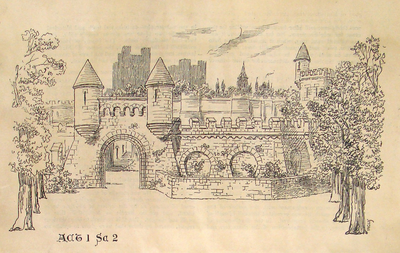

75Sets for the production were constructed in a style that combined realism with high Romanticism. Solid city and castle walls provided plenty of room for the citizens of Angiers and a high point from Arthur to leap from, realistic and illusionistic backdrops and flies left room for massed effects of the crowd of attendants and extras.

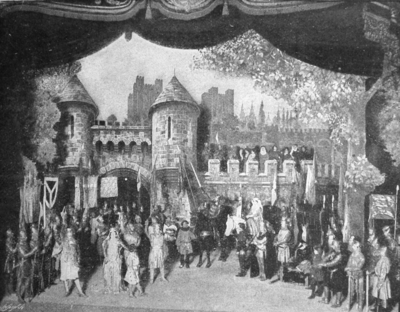

The prompt books provide some sense of the sumptuousness of the production. The entrance of the English forces in 2.1, is accompanied by these instructions:

76Entrance as follows

English Standard-bearers with two knights

10. Knights.

Queen in litter with 8. bearers.

(They place litter down L[eft].C[entre]. the Queen

descends helped by Faulconbridge -- they

raise litter and put it up L[eft].)

4. Knights

King John } Mounted on horses

Blanche }

12. Men at arms.

77This moment in the play is preserved in a photograph that shows the massed effect of the assembled kings and their followers; the forces of France, with Constance and Arthur prominently down stage, are on the left of the photograph, the new arrivals from England with their impressive horses on the right.

78Beerbohm-Tree's production provides a closing bookend to a style of production that had held the stage for almost a century. It is fitting that it should be recorded in the medium that was eventually to recreate his love of spectacle, sound, and elaborate business, fully realized in movies like those of Kenneth Branagh in the late twentieth century: the first silent film ever made on a Shakespearean subject recorded three or four scenes from Beerbohm-Tree's production (Buchanan 64). In due course, as the medium matured, the cinema would make the kind of spectacle the stage could manage seem increasingly less impressive, much as the invention of photography influenced the movement away from representational art.

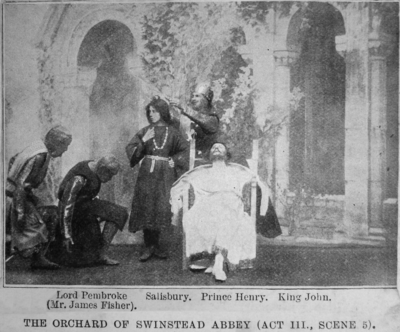

79Only one of these scenes survives: King John's death. Discovered in 1993, the film clip is incomplete, and lasts a brief 75 seconds. It is almost certain that the actors made no significant changes from the stage production, apart from the necessity of filming in a location better lit than the stage at the Haymarket Theatre. On the film set, Tree sits in his chair, speaking and moving, apparently in pain (McKernan describes his movement as "writhing" [35]). At one moment Prince Henry (Dora Senior) kneels and reaches forward, only to be rejected by John, as they are clearly speaking the lines:

80PRINCE HENRY

O, that there were some virtue in my tears

That might relieve you.

KING JOHN

The salt in them is hot.

81A modern eye may feel that Tree's death agonies suggest overacting, of the kind we tend to expect from actors from an earlier age (in our cheerfully patronizing way, conditioned as we are by actors performing in more intimate theaters or in front of the revealing eye of the modern camera). Reaction at the time was quite different; one reviewer of the production observed that

82Mr. Tree stands out from amongst actors for the ghastly realism of his death scenes. . . . King John dies rigid in his chair, and sits, staring into vacancy with awful eyes, until a courtier touches him upon the shoulder, when he collapses into clay.

83Another reviewer commented on the response of the audience: "the stark backward loll of the corpse sent a tremour [sic] through the house" (both passages qtd. in Ellison 295). The film frustratingly ends just before this climactic moment, but a photograph of the final tableau survives.

84It is not surprising that this production has been seen by theater historians as the last gasp of the elaborate "architectural" style of Shakespeare production. It is only in retrospect, however, that the style can be seen as dated; it was enormously popular -- over 170,000 saw it -- and elicited generally very positive reviews. Nonetheless, there were counter-currents in the theater world that would in a few short decades change profoundly the expectations of audiences and the techniques of directors. The pioneering work of the director William Poel reclaimed many of the production values we associate with the original performances of the plays--a largely bare stage, and rapid changing of scene as actors set the context rather than scenery. Poel explicitly mentions Beerbohm Tree as an example of what he sees as an obstacle to a more authentic staging of the plays; responding to Poel's proposal that a Shakespeare memorial, to be erected in London, include "the erection of a building in which Shakespeare's plays could be acted without scenery," Poel reported that "Sir Herbert Tree, as representing the dramatic profession, declared that he could not, and would not, countenance it" (Poel 230-31).