Modern Experimental Productions

Shakespeare in China -- page 4 | next

Whereas Xu Xiaozhong, as a committed revolutionary artist, would never indulge in escapism, many Chinese directors who were given the opportunity to put on Shakespeare deliberately avoided any contemporary relevance in his plays -- particularly since each huaju company already had a certain official quota for presenting plays with modern or revolutionary themes. Most practitioners therefore used Shakespeare to explore a wide range of theatricality. For example, Brecht's "alienation effect" was used in the ball scene of Xu Qiping's Tibetan version of Romeo and Juliet (1982) to emphasize the priority of expressing emotion over the representation of real life. (video the ball scene) Inspired by Peter Brook's work, Xiong Yuanwei in his A Midsummer Night's Dream (1986) also used ropes for the set, but cleverly blended them with a traditional Chinese scenographic principle that "scenery derives from acting."

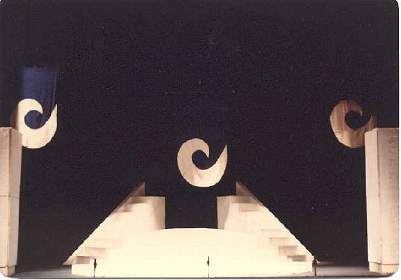

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1986), translated by Zhu Shenghao, directed by Xiong Yuanwei, produced by Chinese Coal Mining Song, Dance and Drama Ensemble. Courtesy of Central Academy of Drama.

Guided by this concept, audiences were convinced by the group of performers that the eleven ropes hanging down on the stage were the magic forest. Hu Weimin in his Antony and Cleopatra for the first time on the Chinese stage used the abstract set and the few cubes in different shapes were used effectively to represent different location.

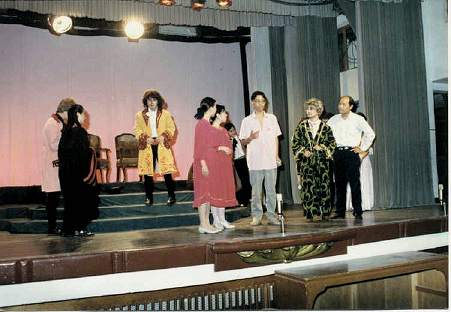

Antony and Cleopatra (1984), produced by the Shanghai Youth Spoken Drama Company, Courtesy of Fang Ping.

In Twelfth Night (1993), He Bingzhu adopted certain components from the Stanislavski System in rehearsals, but went beyond the "realistic boundary" by using stylistic make-up and costuming. The painted faces were not traditional Chinese patterns but originated from various sources such as Western paintings or masks, and some faces were matched by the patterns or colour of the costumes. This arrangement created an intriguing visual effect for the play, because both make-up and costumes lost their realistic conventions in signifying the identity of characters and their function in the plot. On the contrary, they blurred the individuality of the roles, with the faces of performers and their costumes becoming an integral whole. (video an extract which shows the masks and costumes) Lei Guohua in her 1994 Othello arranged the audience around the stage and attempted to break up the separation between the auditorium and the stage. (Video)

Not all productions have chosen to ignore difficult social problems such as the question of racism in The Merchant of Venice. Indeed, when the Shanghai Fudan Drama Club staged the Merchant at the 1994 Shanghai International Shakespeare Festival, Shylock was made the protagonist of the play as a man "of insight who condemns anti-Semitism vehemently and reproaches the Nazis for being so cruel to the Jews." The adapter devised two alternative endings for the play: in one, Shylock effectively lectures the court on modern economic theory; in the other, Shylock agrees to give up his lawsuit on condition that his daughter returns to him, in which case he will also accept Lorenzo as his son-in law. When the court scene was reached during the performance, the audience was invited to supply its own hypothetical verdict for the court hearing.

The Merchant of Venice (1994), directed by Geng Baosheng, produced by Fudan University Theatre Club, photo by Yang Xingliang. Courtesy of Geng Baosheng.

The director and performers would then choose one or more of these hypotheses and rehearse them in front of the audience. The two endings previously written by the adapter could also be blended with the audience's version.

Of Shakespeare performances in huaju, the most radical experiments have undoubtedly been Lin Zhaohua's staging of Hamlet (premiered in 1989) and Richard III (2001). While many found Lin's directorial innovations difficult to understand and argued that these performances failed to communicate effectively with audiences, some critics praised his work as the model for the future development of the huaju form. Lin was not interested in using the productions to comment directly on the current political situation. Nevertheless, the way Lin read the texts was plainly conditioned by the social, political and economic changes that were taking place in China. In the ten years preceding the1989 Hamlet, China had undergone a transformation. Socialism had almost vanished. The old values and morality espoused since the Communist Party seized power in 1949 no longer seemed to make sense. In addition, the crackdown on the students' democracy movement in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989 had further divided people. Some became more radical and political, while more tried not to concern themselves with politics at all, but instead concentrated on making money. Against this background, Lin Zhaohua provided the Chinese audience with a very different presentation of Shakespeare. Instead of a Renaissance "giant," the director envisioned a lonely Hamlet as "one of us."

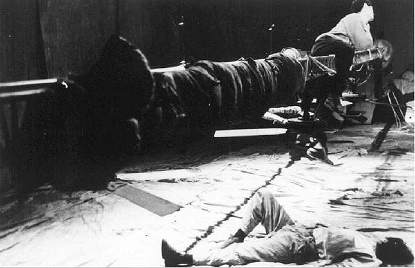

Lin Zhaohua's Hamlet had no use for Westernized make-up, wigs, prosthetic noses, or "doublet and hose" costumes. In their place were the urban clothes and natural faces of contemporary China, bringing Shakespeare's characters into the performers' own world. The style of acting was less demonstrative and more natural than was customary in main-stream productions. The performers did not try to represent "giants" or "clowns," "heroes" or "villains." Nor did they attempt to give audiences any signals denoting the "progressive forces" or "reactionary forces" as orthodox Chinese scholarship tended to demand. Gone too was the elaborate set. The only permanent prop in the production was a barber's chair which symbolized at different times the throne, a bed or a rock near Ophelia's grave. The stage was covered by a huge creased floor-cloth, above which five worn-out ceiling fans constantly rotated. In the duel scene, these ceiling fans were lowered to take part in the fight.

Hamlet (1989 & 1990), by the Lin Zhaohua Workshop; revival (1994), by the Beijing People's Art Theatre. Translated by Li Jianming, directed by Lin Zhaohua and Ren Ming, photo by Su Dexin. Courtesy of Lin Zhaohua.

The most controversial device introduced by Lin in this production was the switching of key character parts among a number of actors. At certain points, for example, the two actors who predominantly played Hamlet and Claudius interchanged roles. At another moment, the actor playing Polonius became Hamlet. The "to be or not to be ..." soliloquy was shared by all three actors. The effect of this was meant to blur the moral opposites in apparently opposed character roles, suggesting that the characters all shared elements of good and evil, honesty and falsehood.

For his latest Shakespeare project, Lin Zhaohua was attracted to Richard III because of the protagonist's cruelty and skilful usurpation. Similar events have been observed many times in Chinese history, but Lin soon abandoned the familiar aspect of the foreign story. Instead, he traced an alien element in the familiarity -- the image of victims and accomplices. The theme of this production was that "those who lack vigilance against schemes are the conspirator's accomplices, though they can also find themselves among the victims." Moreover, "those who are close to you are in fact your never-expected enemies." These ideas did not germinate from any specific incident, but were a summary of Lin's sixty-five years' experience in a world that had witnessed a series of catastrophic upheavals. Should those who were seen as victims, and were actually victims, also take responsibility for the causes of the tragedy? Shakespeare, in scenes such as the lamentation of the three queens in IV iv and the stylized procession of the ghosts in V iii, makes it clear that everyone is Richard's victim. Lin's interpretation implied that these victims' blindness and paralysis had in one way or another assisted or quickened the vice in Richard's nature and his usurpation of power. But this was not staged in a heavy tragic style. Lin attempted to avoid a straightforward presentation of his thought. Rather, he created "cruel games," whereby Richard's conspiracy and murders were carried out on the stage through a series of children's games. (video hawk preying on chicks)