- Edition: King John

Performance History

- Introduction

- Texts of this edition

- Contextual materials

-

- Chronicon Anglicanum

-

- Introduction to Holinshed on King John

-

- Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland 1587

-

- Actors' Interpretations of King John

-

- King John: A Burlesque

-

- The Book of Martyrs, Selection (Old Spelling)

-

- The Book of Martyrs, Modern

-

- An Homily Against Disobedience and Willful Rebellion (1571)

-

- Kynge Johann

-

- Regnans in Excelsis: The Bull of Pope Pius V against Elizabeth

-

- Facsimiles

1Introduction: early performances

The stage history of King John is unexpectedly rich, despite its relative neglect in the twentieth century. It was popular in the eighteenth century, and in the nineteenth set the standard for Shakespeare performances that emphasized spectacle and carefully accurate reconstructions of historical detail in costume and stage settings. King John was the first Shakespeare play to be filmed, with a brief clip of about a minute preserving a glimpse of the stage performance by Herbert Beerbohm Tree in 1899.

2A review of one of the first productions of the current century makes a strong case for the importance of some of Shakespeare's less popular plays when it comes to an understanding of changes in audiences and traditions of staging:

3 Rarely performed plays like King John with their peaks of fashion and troughs of deep neglect, are truer barometers of the time than age-old favourites which never leave the stage. When such plays are revived, it is for a reason. The Victorians loved King John for its passion, especially the part of Constance, whose outraged defence of her son Arthur's claim to the throne thrilled their melodramatic souls. In more recent times, the play has been picked for its politics. In the late 1960s and early 70s, its cynical attitude towards realpolitik and war brought it twice to the English stage. And it is politics which has brought it back now. John blusters to keep his little England from the meddling of France and Rome . . . while doing deals, selling out, changing allegiance, swapping sides and generally doing everything he can to stay in office. (Catherine Bates, Times Literary Supplement 13 April, 2001)

4The reviewer's comment on the opportunity the part of Constance offers an actor is a reminder that King John provides actors with several rewarding roles: in addition to Constance there are the two main male parts, King John and the Bastard, as well several potentially rewarding lesser roles -- King Philip, Pandulph, Hubert, and Lewis. In the discussion that follows, rather than looking at the historical interpretation of the major characters (discussed in the General Introduction [[link to come]], I focus on changes in staging, stagecraft, and the thematic or ideological emphases directors have brought to the play. I discuss the performances of some major actors in the General Introduction [[link to come]] in the section on Shakespeare's characterization; there are also discussions of individual performances in the anthology of early criticism of the play[[link to come]]. My survey of early performances necessarily deals with productions in England, but from the middle of the twentieth century on I include representative North American performances as well.

5Elizabethan stages

Nothing is known of the original production of King John on Shakespeare's stage, other than a general understanding of the advantages and limitations of the early theaters where it may have been performed. There are no clear indications of the company that first performed it, and uncertainty about its date of composition makes it difficult to narrow the range of possibilities. There is some likelihood that the part of Robert Faulconbridge would have been originally played by John Sincklo (also known as Sinckler), an actor known for being particularly thin. The Bastard describes his younger brother in parodic language that suggests Sincklo's build: his legs are "riding-rods" (thin branches or used as whips), and his arms as "eel-skins stuffed" (TLN 148-49). Sincklo performed with various companies from 1590-1604; Strange's, Pembroke's, and the Chamberlain's Men; his name is used as a speech prefix for the Second Player in The Taming of the Shrew (Shr TLN 98), a play that was probably also written in the early to mid 1590s.

6We do know, somewhat unexpectedly, some features of staging that Shakespeare chose not to include; in comparison with The Troublesome Reign of King John (TRKJ), performed by the Queen's Men in the early 1590s, Shakespeare seems deliberately to have avoided the equivalent of modern special effects. TRKJ includes a sequence, quite characteristic of Queen's Men productions, where there is an elaborate stage effect of five moons appearing:

7[King John] Why how now Philip what ecstasy is this?

Why casts thou up thy eyes to heaven so?

There the five moons appear.

Bastard. See, see my lord, strange apparitions.

Glancing mine eye to see the diadem

Placed by the bishops on your Highness' head,

From forth a gloomy cloud, which curtain-like

Displayed itself, I suddenly espied

Five moons reflecting, as you see them now. (TRKJTLN 1747-55)

8In The Troublesome Reign, Peter of Pomfret, the prophet who is summoned to explain the phenomenon, proceeds to discuss with the accompanying lords the meaning of this apparition at some length. The corresponding moment in King John avoids special effects altogether, substituting an evocative description by Hubert of both the event and the reaction of the people of England to it:

9HUBERT

My lord, they say five moons were seen tonight:

Four fixèd, and the fifth did whirl about

The other four in wondrous motion.KING JOHN

Five moons?

HUBERT

Old men and beldams in the streets

Do prophesy upon it dangerously.

Young Arthur's death is common in their mouths,

And when they talk of him, they shake their heads

And whisper one another in the ear.

And he that speaks doth grip the hearer's wrist,

Whilst he that hears makes fearful action

With wrinkled brows, with nods, with rolling eyes.

(TLN 1906-17)

10The actor who performs Hubert is given a fine chance to act out the description as he describes cameo moments with a blacksmith listening to the latest gossip from a tailor, standing "with his hammer, thus, / The whilst his iron did on the anvil cool, / With open mouth swallowing a tailor's news" (TLN 1918-20), while the tailor in turn is so thunderstruck by the news of the invasion of the French that he has "falsely thrust" his slippers "upon contrary feet" (TLN 1923).

11In contrast with the special effects used in TRKJ, King John requires very few props. Standard items would be

- a throne, as John tells his lords, "Here once again we sit, once against crowned" (TLN 1718);

- a crown, as John yields up "the circle of his glory" to Pandulph (TLN 2168);

- various papers (a warrant for Arthur's death, a contract between the French and English nobles, and a letter from Cardinal Pandulph);

- swords and the general paraphernalia of battle, possibly including anachronistic pistols, since cannon are mentioned in the dialogue;

- Hubert may brandish either pistol or bow when he challenges the Bastard: "Who's there? Speak ho! Speak quickly, or I shoot" (TLN 2551-2);

- Arthur's scene with Hubert calls for a chair, ropes, brazier, and irons to put out his eyes;

- at the close of the play, John is brought in onstage in some kind of chair.

But the most striking props would have been those associated with Austria--his lion's skin, and in due course his head: "Alarums, excursions. Enter Bastard with Austria's head" (TLN 1283-4). Sound effects also are standard and minimal: cannon, alarums and excursions, drums and trumpets.

12If Shakespeare avoided elaborate stage effects, he did use one common feature of the early theater, the "upper stage"--an area at the back of the stage where one or more actors could appear above the action (one thinks of Juliet's window, or the walls of Barkloughly castle where Richard II appears just before he is taken prisoner by Bolingbrook). The citizens of Angiers appear above the stage and negotiate with both the French and English forces, watch the ensuing battle, then negotiate again, finally opening their doors to both forces as they are temporarily in accord. Later Prince Arthur leaps from a wall to his death (TLN 2005-06), in a scene that is something of a challenge in a modern production, and which is a puzzle for us to understand in its early performances: the usual reconstructions of the upper stage make it a full storey above the playing performance--a rather major leap for a child actor, and one which might in truth end up with broken bones.

13The stage, with its two main doors, would also have provided the opportunity for strikingly antiphonal entries by the opposing armies in the confrontation before Angiers, as the stage direction makes clear: "Enter the two Kings with their powers, at several doors" (TLN 646 ). The end of this scene provides a visual image of the agreement of these opposed forces as they would exit together from the same door (creating something of a traffic jam perhaps); the entry of Constance from the other door, accompanied only by Arthur and Salisbury, would again have provided a visual counterpart to her isolation. A subdued echo of the antiphonal entries of the kings and their armies comes in the penultimate scene of the play when Hubert and the Bastard enter through different doors: "Enter [the] Bastard and Hubert, severally" (TLN 2550); once again they leave together. The Elizabethan stage would have made the later scenes in the play, often criticized as being less coherent than the first half, more fluid than may seem the case on the page.

14The Restoration and early nineteenth century

King John held the stage with some regularity through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The first Restoration production had Dennis Delane in the title role at Covent Garden in 1737; it went through several performances that year (Schneider). Delane acted with his more illustrious contemporary David Garrick, and in 1745 they performed together, with Delane taking the part of the Bastard to Garrick's king (see the selection of comments by Thomas Davies from the Memoirs of the Life of David Garrick, and Pedicord). These performances provided the stage for a kind of duel between rival versions of the history, as they went head-to-head with a radical adaptation of the play by Colley Cibber, who had earlier created a stage success with his rewriting of Richard III in a form that held the stage for over a century. But when Cibber announced that he was rewriting King John, he was met with mockery (Cousin 4).

15The controversy signaled an important shift in the public perception of Shakespeare's work. Restoration audiences were accustomed to versions of Shakespeare rewritten for their tastes--Nahum Tate's King Lear is the best known, but there were many other adaptations, penned by D'Avenant, Dryden, Shadwell, Cibber and others. Cibber is most often remembered as the "hero" of later versions of Pope's Dunciad. Cibber was a staunch protestant: finding King John insufficiently anti-Catholic, he rewrote it with added anti-Catholic vituperation. In his dedication to the Earl of Chesterfield, he explains his reasons:

16In all the historical Plays of Shakespear there is scarce any Fact, that might better have employed his Genius, than the flaming Contest between his insolent Holiness and King John. This is so remarkable a Passage in our Histories, that it seems surprising our Shakespear should have taken no more Fire at it. . . . It was this Coldness then, my Lord, that first incited me to inspirit his King John with a Resentment that justly might become an English Monarch, and to paint the intoxicated Tyranny of Rome in its proper Colours. . . . I have endeavour'd to make it more like a Play than what I found it in Shakespear. . . (Sigs. A3, A4)

17His Prologue, "Spoke by the Author," damns Shakespeare's play with faint praise, as he develops an elaborate extended metaphor in justifying his revision:

18The hardy Wretch, that gives the Stage a Play,

Sails in a Cockboat, on a tumbling Sea!

Shakespear, whose Works no Play-wright could excel,

Has launch'd us Fleets of Plays, and built them well:

Strength, Beauty, Greatness were his constant Care;

And all his Tragedies were Men of War! . . .

Yet Fame, nor Favour ever deign'd to say,

King John was station'd as a first rate Play;

Though strong and sound the Hulk, yet ev'ry Part

Reach'd not the Merit of his usual Art!

19Cibber may not have won the day with his adaptation, but Shakespeare's play was not universally admired. The final comment at the end of Garrick's acting edition, derived from the prompt-book, puts Shakespeare just a short distance ahead of Papal Tyranny:

20Much the greater part of this Tragedy is unworthy its author; a rumble-jumble of martial incidents, improbably and confusedly introduced; the character of Constance intire, four scenes and several speeches of Faulconbridges, are truly Shakespearean. Colley Cibber altered this piece, but, as we think, for the worse; it is more regular, but more phlegmatic, than the original. (64)

21Perhaps because of this "phlegmatic" nature, Papal Tyranny was not a success, while King John continued to hold the stage for the remainder of the eighteenth century and much of the nineteenth. In 1745, during the controversy over Papal Tyranny, David Garrick performed John; ten years later he had decided to take on the part of the Bastard, perhaps because the character is more sympathetic, or provides more opportunity for an actor; in 1760 he played the Bastard to Richard Brinsley Sheridan's King. The Introduction to the acting edition of this production is frank about the play's apparent unevenness of invention:

22King John most certainly deserves to live on the stage, but they must be a very good set of performers who can sustain it; several scenes are highly interesting, others extremely prolix and flat. (3; sig. B2)

23Despite this distinctly qualified approval, the play held the stage for a century after Garrick. The next major production (1783), by John Philip Kemble, set the form of the play for a century; his response to the perceived prolixity of the play was to institute substantial cuts, a practice that was followed by later companies.

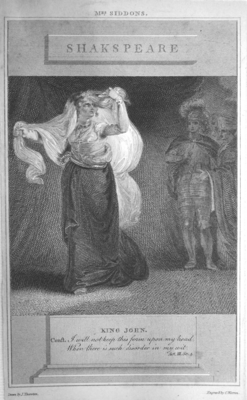

Kemble performed the play many times; William Hazlitt's review of a performance (View of the London Stage) was at best lukewarm, but he saw it after the redoubtable Mrs. Siddons had made the part of Constance her own for a generation. Mrs. Siddons played Constance in a style that evinced considerable praise:

24 [Mrs. Siddons] was ere long regarded as so consummate in the part of Constance, that it was not unusual for spectators to leave the house when her part in the tragedy of King Johnwas over, as if they could no longer enjoy Shakespeare himself when she ceased to be his interpreter. (Thomas Campbell, Life of Mrs. Siddons [London 1834], qtd. in Candido, 83)

See also the fuller discussions of Mrs. Siddons as Constance from Campbell's Life and George Fletcher on King John.

25Geraldine Cousin perceptively points out the value of King John to the star actor, given the general paucity of major female roles in Shakespeare. The general taste of the period was for a more operatic drama with fine scenes and speeches; what are today often seen as difficulties for an actor were relished in the nineteenth century.

26 From 1800, Kemble was joined by his younger brother Charles, who played the Bastard.

27The strong cast included Mrs. Siddons, still playing Constance.

28King John as authentic history

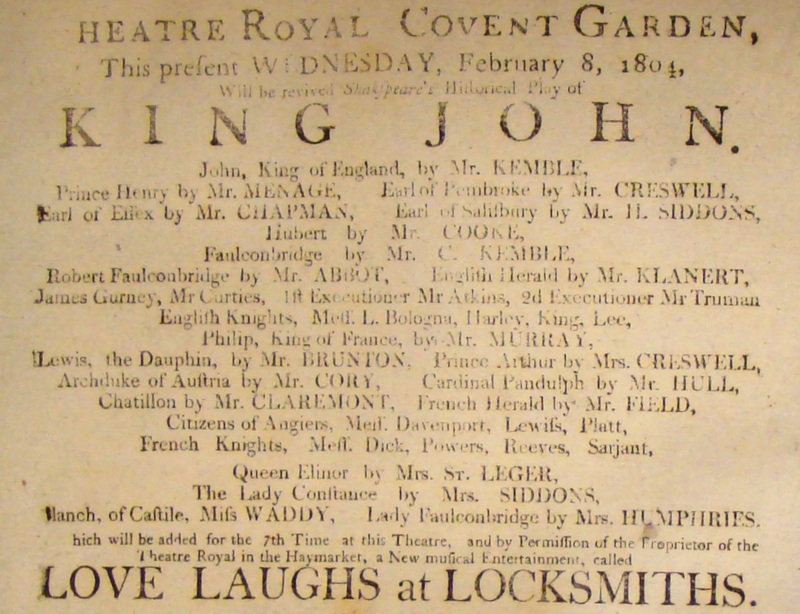

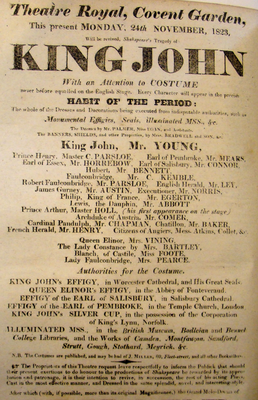

Charles Kemble continued to play the part when he teamed first with Charles Mayne Young, then with William Charles Macready. In 1823, with Young as King John, he performed Faulconbridge in a production that broke new ground in its use of stage sets and costumes.

29Charles Kemble had asked the "dramatist and antiquary" James Planché to assist him in preparing a production of the play that would have both sets and costumes authentic to the period of John's reign (Cousin 28-32). As the playbill for the production boasts, Planché spent many hours finding examples of dress from John's time; the playbill for the performance boasts that the production is presented "With an Attention to COSTUME never before equaled on the English Stage. Every character will appear in the precise HABIT OF THE PERIOD." The playbill goes on to list as Planché's sources: funeral effigies in Worcester Cathedral and various churches, an engraved silver cup, illuminated manuscripts, and recently published works on earlier habits of clothing and dress. For almost a century after this production, minutely accurate costumes and settings became the general rule for Shakespeare productions.

30 Macready's King John is exceptionally well documented. His prompt book and stage sets are preserved in the Folger Shakespeare Library, and have been published by Charles Shattuck (1962) in a collection that also includes the costume designs for the production and a carefully researched Introduction. Macready's prompt book was used by Charles Kean; Shattuck reproduces Kean's version of the play, since it "shows accurately enough the manner of Macready's staging of the play in 1842, and at the same time shows how Kean first staged it in 1846" (7). The emphasis in the production was on spectacle, not only with the elaborate and authentic costumes, but with carefully grouped staging, and choreographed movements on stage, especially in the various battles, which involved enough "extras" to make them appropriately impressive. Macready used extensive musical cues: frequent trumpets and drums especially in the battle scenes, wind instruments for martial music, and organ for the ecclesiastical moment later in the play when John yields up his crown (5.1). Macready's interpretation was noted for the strong transition he created mid-way through the play, at the point of King John's greatest triumph after winning the battle against the French and capturing Arthur. Macready signaled the change in John from victory to anxiety as he realizes he must somehow deal with the continuing threat of Arthur. Instead of a triumphant entry after the battle, the prompt book, in an entry that gives some idea of the extent of the additional characters Macready introduced in the interest of spectacle, makes clear the exhaustion of those who have won the battle, and sets the mood for the gloomy scene where John persuades Hubert to undertake the task of killing Arthur:

31[Enter] Essex, Norfolk, Fitzwalter -- and party. Enter R[ight] U[pper] C[enter] and go slowly -- as tho' fatigued -- to L[eft] D[ownstage], then Pembroke -- followed by Oxford, Arundel, and 2 English Knights, who go down, R, in same manner, -- 4 Esquires precede K John, who is speaking to the Queen Mother as they both enter -- after them Hubert, with Arthur, -- and lastly the Bastard. (Shattuck 239)

See also the reviews of Macready's performance recorded by Cowden Clark and others.

32Charles Kean, son of the more famous Edmund Kean who had played the part of King John in 1818, performed the play some years later; a review of this performance in the London Illustrated News (1852) provides some insight into the appeal both of the play and of the central character; the troubling character of King John was understood as a moral allegory, a portrait of the inevitable corruption that came with barbaric times:

33The tragedy of "King John," with its magnificent appointments, still continues to prove attractive. The character of the hero, notwithstanding his crimes, commands sympathy, for the mind habitually recognizes in him the majesty of England and of the age in which he lived, rather than the mere individual. He is a grand impersonation of the state. . . .To us this picture of regal sin and suffering has a deep meaning, and moves the reflective soul to intense emotion. . . .[More . . .]

34The illustration that accompanies the review does not show John, but the great moment of pathos in the play when little Arthur pleads with his jailer Hubert to spare his eyes:

Perhaps the character of the Prince [Arthur] was never more beautifully interpreted than my Miss Kate Terry, whose exquisite acting at Windsor Castle in the part much pleased her Majesty.

35With a splendidly Victorian moral sense, the reviewer concludes, "Such dramas are calculated to make the spectator brave and good" (London Illustrated News, April 17 1852).

See the review of Kean's performance as King John by Frederick Hawkins in his Life of Edmund Kean.

36A nineteenth-century footnote: delicacy and schoolboys

In the interests of making the reader good, if not brave, the Reverend John Valpy, Headmaster of Reading College anticipated the thorough sanitation of Shakespeare's texts by Dr. Bowdler by almost two decades. In 1803 he created an acting version of King John that smoothed many corners and made the play palatable to the parents of the boys at his school. Valpy carefully omitted references to the Bastard's origins (and in fact left out the whole first act). As he made the language more acceptable, he managed to destroy the verse:

| Shakespeare | Valpy |

| I will instruct my sorrows to be proud, | I will instruct my sorrows to be proud, |

| For grief is proud and makes his owner stoop. | For grief is proud and dignifies the mourner, |

| To me and to the state of my great grief, | To me, and to my venerable grief, |

| Let kings assemble . . . | Let kings assemble . . . |

(Quoted in Odell, 71)

37We may be grateful that this adaptation remained a footnote in the stage history of King John.

38 King John refracted through burlesque

To a modern reader, the adaptation by Valpy seems unintentionally parodic in its solemn desire to make the play respectable. It is a measure of the popularity of King John that it was given a deliberately burlesque treatment. Written by Gilbert Abbott A'Beckett, and published in 1837, King John(With the Benefit of the Act): A Burlesque provides, no doubt unwittingly, some revealing insights into audience reception of Shakespeare's original. Burlesque gains much of its humor by deflating and parodying high culture; it will seize on moments that are in one way or another memorable for the viewers who have seen the original, and who will therefore appreciate a distorted reflection of it. Through this somewhat warped mirror we can reconstruct some sense of the nineteenth century reception of King John, and even see some remnants of the nineteenth-century staging. There are fewer verbal echoes than we might expect, though there are several that quote -- and deflate -- moments of high drama. The kings greet each other before Angiers:

39 K. John. (L.C.) Peace be to France, at least, that is to say

If France, will let us have it, our own way.

Phil. (R.C.) Peace be to England, that is if t'will bow,

To our authority without a row.

(A'Beckett TLN 123-6; compare Jn 2.1 TLN 381-87)

40 In moments like these, we can imagine that the actors would not only echo the wording of Shakespeare, but exaggerate the mannerisms of actors like Macready, who had performed the part as recently as November 1836. The printed text of the burlesque includes details about the pseudo-medieval costumes the actors wore, and has as its frontispiece an illustration of the absurd costume for King John, "Breast plate, with spike in the centre, and spikes on his knees and elbows -- helmet, with a weather-cock, and N. E. S. W. on it." Richard Schoch remarks that the costume "sneeringly alludes to the vogue for historically accurate stage dress," and suggests that the weather-cock variously "expresses the provisional and mutable nature of theatrical performance," and stands for "Naughty English Wrongful Sovereign" -- though this acronym rearranges the letters as they are cited in the text of the work. More probable is the rather obvious symbolism for a king who in the public mind, in Shakespeare's original, and in the reductio ad absurdum of the burlesque, is seen to change his allegiance as the political wind -- "commodity" -- blows.

41King John's part is a starring role in the burlesque (he has six of the nine songs in the play), so it is not surprising that he has many moments that illuminate the original part. Audiences must have enjoyed his instant knighting of the Bastard:

42 K. John. I like you, sir -- your valour to requite,

I'll make of you upon the spot a Knight

(A'Beckett TLN 66-67),

43and even in the nineteenth century they may well have relished his defiance of the pope, reduced of course to a joke:

44 (Enter Cardinal Pandulph, L)

Pandulph. King John, I've got a message from the pope.

K. John. None of his usual nonsense, sir, I hope. . . .

Go tell the pope, the king does as he pleases,

And at his holy threats he only sneezes.

(A'Beckett TLN 239-44)

45More interesting is the fact that the burlesque retains the news of Eleanor's death and provides John with an exaggerated response to it, perhaps suggesting a strong stage tradition for this moment.

46Many moments in Shakespeare's original will be unfriendly to the comic world of burlesque, so it is no surprise that Arthur's scene with Hubert and his subsequent death are wholly omitted. But the burlesque provides a full treatment of the temptation of Hubert, parodying John's flattery and his habit of repeating Hubert's name:

47But Hubert, Hubert, Hubert, throw your eye

On that young lad, that now is standing by . . .

(A'Beckett TLN 301-02)

48And the moment where Hubert brings news of the mysterious appearance of five moons and reports the unhealthy speculations of the common people receive full treatment, complete with comic compound rhyme:

49 Hub. To night, my lord, they say twelve moons were seen,

Three pink, three orange, half-a-dozen green,

And in addition to this crowd of moons,

There have been five and twenty fire-balloons.

K. John. Oons! -- moons! -- balloons!

Hub. The people in the street,

Shake their heads frightfully, whene'er they meet;

And he that speaks, doth grip the hearer's button,

While what he says the other chap doth glut on.

(A'Beckett TLN 352-60)

50Some of this, no doubt, comes from a cheerful sense that the audience is superior to what will now be seen as superstitions rather than threatening portents, but it is certainly possible that many in Shakespeare's audience would have had a similar, if less patronizing reaction. The movement from the naïve stage spectacle of The Troublesome Reign to Hubert's report of the moons makes available to Shakespeare's audience an ambivalence that has become a certainty ripe for comic treatment by mid nineteenth century.

51The Bastard in Shakespeare already has some speeches where he is close to parodying the more serious-minded characters, and predictably gets some very good moments in the burlesque. His "wild counsel" is well received, and his aggressive taunting of Austria needs only a minor change in vocabulary to become unthreateningly comic:

52[Constance] That hide is quite enough to make one grin,

Thou perfect Neddy in a Lion's skin.

Aus. Oh, that a man such language would begin.

Faul. (From behind John's chair) Thou thorough Neddy in a Lion's skin.

Aus. You daren't say that again, I bet a pin.

Faul. (advancing.) You thorough Neddy in a Lion's skin.

K. John. We like not this, such fools I never saw,

You both seem Neddys by your length of jaw.

(A'Beckett TLN 230-37)

53Women on stage in the nineteenth century had become major public figures, and demanded dramatic roles to display their talents; In King John, the grief of Constance was something of a yardstick for measuring the rival talents of Mrs. Kemble, Mrs. Siddons or Helen Faucit. The burlesque includes a solo for Madam Sala, who played Constance, and she has some fine opportunities for emoting over Arthur's ill fortune, culminating in her determination to sit and demand that the kings attend her. To the Herald who has summoned her, she declaims, in phrases that clearly recall Shakespeare's originals:

54 Const. But thou shalt go without me -- do you see,

If the Kings want me, they must come to me.

. . . . .

Here I and sorrow sit, (Throwing herself on the ground) let Kings come bow,

This is my throne, I'm ready for a row.

(A'Beckett TLN 196-203)

55The earlier clash between the two women, Constance and Eleanor is reduced to a single line each, followed by a sardonic comment from Austria. Though the interchange between the women was routinely cut severely in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it is clear that enough of it survived to invite parody:

56[Philip] You do usurp the crown that should be his.

Elin. (L.) Whom do you call usurper, plain Phiz?

Const. (R.) I'll answer that your son's the man he means.

Aus. (R. corner.) There'll be a rumpus with the rival Queens.

(A'Beckett TLN 129-32)

57In at least two places, the burlesque may point to staging practices of the nineteenth century productions it is parodying. The text makes clear that, in the burlesque at least, the kings physically held hands before breaking apart under duress from Pandulph; and in the scene where John struggles to communicate his desire for Arthur's death to Hubert, he is to be imagined using non-verbal cues to support his hints:

58 Hub. Great king, you know I always lov'd you well,

Then why not in a word your wishes tell? --

Why roll your troubled eye about its socket?

(A'Beckett TLN 294-96)

59If Shakespeare's King John has a somewhat equivocal conclusion (see the General Introduction), the farce of A'Beckett's ending leaves no room for subtlety or nuance:

60 Enter all the Characters for the Finale, R[ight]. & L[eft].

Fate comes, we needs must take it, and not pick it,

Bring me the bucket, for I'm going to kick it.

Slow Music -- The King dies.

(A'Beckett TLN 466-72)

61And for the finale, to the music of La Somnambula (hot off the press from its first performance in Milan, 1831), John rises to join the performance, reassuring the audience that he'd not "the slightest idea of dying" (A'Beckett TLN 478).

62Herbert Beerbohm Tree's production, 1899

On more conventional stages, King John was performed by Samuel Phelps in the 1860s, and by Osmond Tearle for the first time in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1890. Tearle retained the tradition of historical accuracy; a reviewer from the Birmingham Post commented that Tearle's "Make-up was very correct, being taken from the picture of the King in the National Gallery. Tearle's acting of the scene with Hubert must have been suitably villainous, since it "called forth a burst of applause, in which some hisses were even mingled." The part of King John was not attempted by the later nineteenth century Shakespearean tragedian Henry Irving, though his edition of the plays, printed in collaboration with Frank Marshall, indicates the cuts he might well have used had he chosen to produce the play (the cuts he indicates follow Macready closely). The Introduction to King John in this edition may indicate Irving's reason for not taking on the part, since it suggests that the king is an unsympathetic figure, and the play therefore anticlimactic (3:157). It is also true that Irving did not perform the king in Henry V either; an alternative possibility is that the Victorian pax Britannicamade the need for patriotic English kings less pressing.

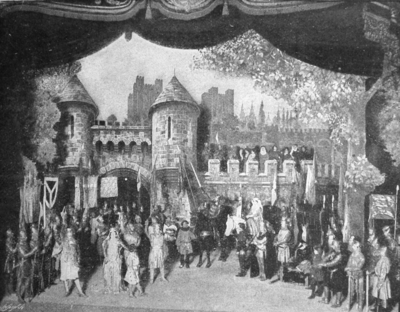

63The pinnacle of spectacular nineteenth-century productions of King John was reached at the close of the century--1899--in a production by Herbert Beerbohm Tree. King John had not been performed for thirty years, so Tree's audience would for the most part not have seen the play performed. Tree's production was magnificent, with elaborate scenery, and involved a huge cast in which even the relatively minor nobles presented on stage were adorned with multiple followers, each in their respective livery. Though not quite a cast of thousands, the number involved was, to modern playgoers, no less extraordinary--three hundred and eighty five "supers" in addition to the basic cast of about twenty. Until very recently, editors discussing the performance history of King John have tended to dismiss this production as an example of excessive, even destructive spectacle: "Beerbohm-Tree's fancy staging in . . . in its very excess may have killed the play. By outdoing what had been done in earlier productions, Tree set out to please the eye or amuse the audience at any cost to the drama, no matter how intrusive" (Beaurline 19). James Ellison, writing about the surviving film fragment from Tree's production describes it as belonging to an "extravagant and now outmoded tradition" (294). Extravagant it certainly was, but it is surely inaccurate to describe a penchant for spectacle as outmoded: modern stage technology permits extraordinary spectacle in the staging of musicals (and even sometimes of Shakespeare), though live horses may be a thing of the past. The now-dominant medium of film gains much of its appeal from spectacular on-location shots, and increasingly the excitement of special effects-- we have only to think of recent Shakespeare films from Kenneth Branagh, Baz Luhrmann, and others to realize that love of spectacle has not altogether disappeard from Shakespearean performance.

64It is perhaps unfair to cite Ellison's lapse into a somewhat unquestioning acceptance of earlier critical judgment at this point, for his study of Tree's production is both nuanced and wide-ranging. He builds on the earlier work of Barbara Kachur, who pointed out the importance of contextualizing the production within the politics of the time; King John is, after all, an intensely political play. Kachur explores impact on the production of the looming advent of the second Boer war, seeing Tree as fostering patriotic support for the imperialism that lay behind the war. Ellison complicates this interpretation, pointing out that contemporary reviews saw the play in strikingly varied ways, either as supporting or questioning the government's agenda. In the process, Ellison highlights the "awkward questions and subtexts" of both Shakespeare's text and Tree's staging of it (304). Ellison also demonstrates the importance to the production of the currently sensational Dreyfus affair in France, in which Albert Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army, had been falsely accused of treason. A few months before the first night of Tree's production, the French army has been forced to initiate a second trial, in the light of new evidence, and the whole affair had been the subject of much anti-French comment in England. Thus the play's potentially equivocal patriotic passages, and its portrayal of a central government deeply flawed by corrupt practices, were intensely topical.

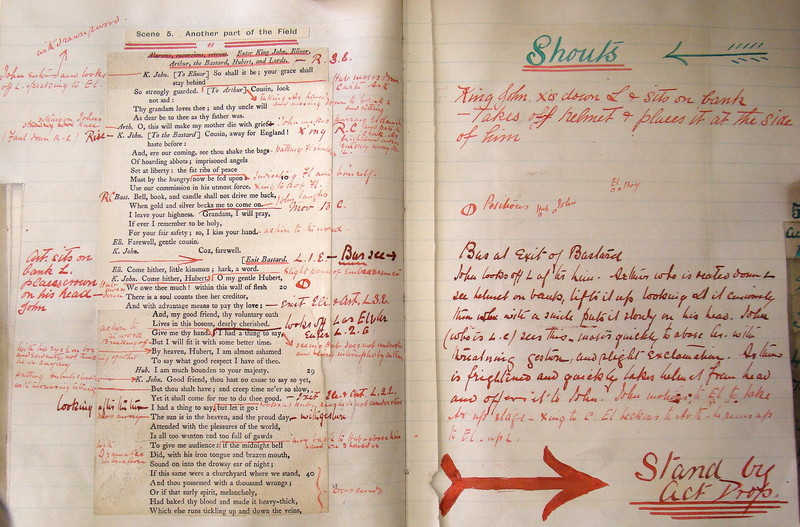

65Contemporary reviews of Tree's King John were kinder than more recent critics. No less a reviewer than George Bernard Shaw devoted two long and laudatory reviews to the production, singling out the interpolated jester, the use of music and chanting, and the stage business his "errant memory" recalled. Tree's King John was certainly inventive in its stage business, as well as spectacular in sets and costumes. Three examples will give a sense of the way his theatrical sense extended the text in a manner that is remarkably like modern film in its use of the visual to explore character, and in many places, a sound track to heighten emotion and to comment on the action. The first example is the much-cited moment in the play when John hints to Hubert his desire that Arthur be killed (3.2, TLN 1259-1370). The staging makes much use of flowers (daisies, apparently) that are part of the set: Arthur innocently picks them; John uses his sword to cut them. Just before this moment there is some business no less symbolic (or melodramatic, perhaps). As the Bastard exits, Arthur is playing with a helmet he finds, putting it on his head. John sees this, moves "quickly to abuse Ar[thur]. with threatning gesture, and slight exclamation." Arthur, frightened, offers the helmet to John.

66Somewhat later in the play, in the scene when John discovers that Arthur has after all not been murdered by Hubert (4.2, TLN 1974-1994), the prompt book first provides a running commentary on John's reaction to Hubert's narrative, then relates the extensive business that follows Hubert's exit. In this transcription, descriptions of action are italicized, while music cues are in roman type.

|

K. John. Out of my sight, and never see me more. My Nobles leave me, and my state is braved, Even at my gates, with ranks of foreign powers; |

[With gesture of dismissal] Clock strikes 10. Distant Chant. Monks enter on platform-- L. & exit into chapel -- C. at back. |

| Nay, in the body of this fleshly land, This kingdom, this confine of blood and breath, Hostility and civil tumult reigns |

[beating his breast] |

| Between my conscience and my cousin's death. | Chant dies away |

|

Hub. Arm you against your other enemies. I'll make a peace between your soul and you. |

|

| Young Arthur is alive. This hand of mine | Chant |

| Is yet a maiden and an innocent hand, Not painted with the crimson spots of blood. Within this bosom never entered yet The dreadful motion of a murderous thought, And you have slandered nature in my form, Which, howsoever rude exteriorly, Is yet the cover of a fairer mind Than to be butcher of an innocent child. |

[John during this speech has at first his head buried in his arms -- then gradually as if expecting something which he fears is too good to be true hysterically rising and throwing himself into Hubert's arms] |

| Young Arthur is alive. | Music -- L. Then dies away |

|

K. John. Doth Arthur live? O, haste thee to the peers, Throw this report on their incensèd rage, And make them tame to their obedience. Forgive the comment that my passion made Upon thy feature, for my rage was blind, And foul imaginary eyes of blood Presented thee more hideous than thou art. O, answer not, but to my closet bring |

[hysterically rising and throwing himself into Hubert's arms] |

| The angry lords with all expedient haste. | Exit Hub. -- R. At back. |

| I conjure thee but slowly: run more fast! | [Calling after him.] |

67The stage business that follows, as the act closes, focuses on John's internal struggle, combining a reminder of his political cunning with a suggestion that the action by Hubert that has (apparently) delivered him from his own villainy is a sign to him that he should renew his faith. In the context of the disappointment that is to follow, the stage business underlines Shakespeare's deeply ironic treatment of this episode, while providing Tree with an opportunity to deepen his characterization of John. On stage as Hubert leaves, John is still holding the warrant for Arthur's death, handed to him earlier by Hubert. The prompt book continues:

68John rushes down stage -- with an hysterical laugh -- then sees document in hand -- and with a cunning look sees brazier and puts warrant on the top -- watches it burn then hears chant -- crosses himself -- face up -- with green focus lime on -- then moves upstage -- faltering -- when in middle of steps with arms up to cross:-- TABLEAU CURTAINS.

69Mention here of the tableau curtains is a reminder of the most controversial of Tree's decisions in staging the play: the addition of two tableaux. The first, of the second battle between the English and French armies outside Angiers, came between Tree's fourth and fifth scenes (in the middle of 3.2 in this edition, TLN 1296), and employed horses as well as a large cast of extras. In the original, the Bastard had just entered with Austria's head; this stage effect, however, must have been considered too gruesome for late nineteenth century sensibilities, so is omitted by Tree. Instead, as the Bastard proclaims "for very little pains / Will bring this labor to an happy end" (TLN 1296-96), Tree's prompt book reads "Exit John . . . Enter Austria & 4 Men-at-arms who attack Bas[tard]. & Hub[ert]." Tableau curtains fall, allowing the cast and horses to assemble on stage. Designed by Joseph Harker, the tableau is reminiscent of the woodcuts illustrating battles that Shakespeare would have found in his edition of Holinshed's Chronicles.

70The second tableau, inserted after Tree's second intermission (between 4.3 and 5.1 in this edition), was a kindly attempt to make Shakespeare more knowledgeable about the important events in the reign of King John: surrounded by his disaffected nobles, the king signs that important document so glaringly ignored by Shakespeare, Magna Charta. The program for the production included a discussion of the importance of Magna Charta, indirectly justifying the inclusion of the tableau:

71The granting of Magna Charta--the most important event in John's reign and one of the most solemn moments in our history--finds no mention in Shakespeare's play. Of course, the Charter was no novelty, nor did it claim to establish any new constitutional principles. But it came at a time when the pressure of the nobles, the despotism of the king, and the power of the clerics threatened to stifle the English constitution. Magna Charta gave back to the people that government of themselves which in a century-and-half of foreign dominion and of foreign wars had been denied, or at least waived aside. (See the full passage.)

72The absence of any mention of the Charter is discussed in the General Introduction [[link to come]].

73Costumes and stage sets were as elaborate as the tableaux. Percy Anderson's costumes, remarkable in their artistic quality, combined historical accuracy with elegance and beauty, and his drawings of major characters are strikingly accurate in catching the faces and figures of the actors who were to play the parts. The collection in the Theatre Collection at the University of Bristol is extensive, with over a hundred and seventy sketches, but it clearly does not, even so, include the whole cast. Nonetheless the collection gives a remarkable sense of the depth of design and complexity of the production: a single noble is accompanied by sketches for a servant, page, knight, and esquire, all part of his retinue; supernumerary characters abound, from the Archbishop of Canterbury to multiple monks; there is even a court jester who was involved in a piece of business that has caught the eyes of earlier writers on the stage history of King John (Beaurline 19, Cousin 45). Bernard Shaw's lengthy review of Tree's production describes some of the jester's actions -- among other things he helps the unattractive Robert Faulconbridge offstage with a blow of his bladder (cited from the transcription in Furness, Variorum; see [[link]]the full review).

74Costumes are carefully designed to emphasize character: the ladies accompanying Eleanor, Constance, and Blanche are all given costumes appropriate to their mistresses; and villains -- Hubert and his two Executioners (Murderers) are suitably dressed in dark, threatening colours.

More important characters had more than one costume: in addition to his initial, suitably royal outfit, John is given a dark, somber dress for his later scene with Pandulph, the Bastard has more than one flamboyant outfit (one is shown here) and Arthur has a second costume for his disguise as he attempts to escape. The sketches provide some hints as to production choices; both Arthur and Prince Henry are portrayed as very youthful -- if anything, Henry appears to be younger than Arthur -- as Tree picks up on Shakespeare's characterization of both as boys, retiring rather than plunging into the world of war and politics.

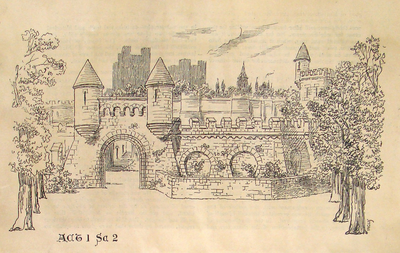

75Sets for the production were constructed in a style that combined realism with high Romanticism. Solid city and castle walls provided plenty of room for the citizens of Angiers and a high point from Arthur to leap from, realistic and illusionistic backdrops and flies left room for massed effects of the crowd of attendants and extras.

The prompt books provide some sense of the sumptuousness of the production. The entrance of the English forces in 2.1, is accompanied by these instructions:

76Entrance as follows

English Standard-bearers with two knights

10. Knights.

Queen in litter with 8. bearers.

(They place litter down L[eft].C[entre]. the Queen

descends helped by Faulconbridge -- they

raise litter and put it up L[eft].)

4. Knights

King John } Mounted on horses

Blanche }

12. Men at arms.

77This moment in the play is preserved in a photograph that shows the massed effect of the assembled kings and their followers; the forces of France, with Constance and Arthur prominently down stage, are on the left of the photograph, the new arrivals from England with their impressive horses on the right.

78Beerbohm-Tree's production provides a closing bookend to a style of production that had held the stage for almost a century. It is fitting that it should be recorded in the medium that was eventually to recreate his love of spectacle, sound, and elaborate business, fully realized in movies like those of Kenneth Branagh in the late twentieth century: the first silent film ever made on a Shakespearean subject recorded three or four scenes from Beerbohm-Tree's production (Buchanan 64). In due course, as the medium matured, the cinema would make the kind of spectacle the stage could manage seem increasingly less impressive, much as the invention of photography influenced the movement away from representational art.

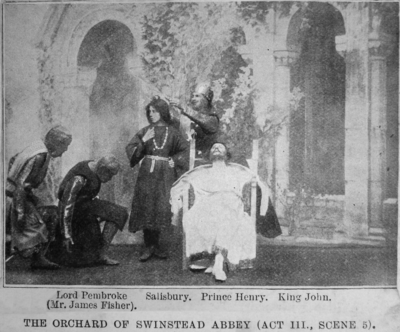

79Only one of these scenes survives: King John's death. Discovered in 1993, the film clip is incomplete, and lasts a brief 75 seconds. It is almost certain that the actors made no significant changes from the stage production, apart from the necessity of filming in a location better lit than the stage at the Haymarket Theatre. On the film set, Tree sits in his chair, speaking and moving, apparently in pain (McKernan describes his movement as "writhing" [35]). At one moment Prince Henry (Dora Senior) kneels and reaches forward, only to be rejected by John, as they are clearly speaking the lines:

80PRINCE HENRY

O, that there were some virtue in my tears

That might relieve you.

KING JOHN

The salt in them is hot.

81A modern eye may feel that Tree's death agonies suggest overacting, of the kind we tend to expect from actors from an earlier age (in our cheerfully patronizing way, conditioned as we are by actors performing in more intimate theaters or in front of the revealing eye of the modern camera). Reaction at the time was quite different; one reviewer of the production observed that

82Mr. Tree stands out from amongst actors for the ghastly realism of his death scenes. . . . King John dies rigid in his chair, and sits, staring into vacancy with awful eyes, until a courtier touches him upon the shoulder, when he collapses into clay.

83Another reviewer commented on the response of the audience: "the stark backward loll of the corpse sent a tremour [sic] through the house" (both passages qtd. in Ellison 295). The film frustratingly ends just before this climactic moment, but a photograph of the final tableau survives.

84It is not surprising that this production has been seen by theater historians as the last gasp of the elaborate "architectural" style of Shakespeare production. It is only in retrospect, however, that the style can be seen as dated; it was enormously popular -- over 170,000 saw it -- and elicited generally very positive reviews. Nonetheless, there were counter-currents in the theater world that would in a few short decades change profoundly the expectations of audiences and the techniques of directors. The pioneering work of the director William Poel reclaimed many of the production values we associate with the original performances of the plays--a largely bare stage, and rapid changing of scene as actors set the context rather than scenery. Poel explicitly mentions Beerbohm Tree as an example of what he sees as an obstacle to a more authentic staging of the plays; responding to Poel's proposal that a Shakespeare memorial, to be erected in London, include "the erection of a building in which Shakespeare's plays could be acted without scenery," Poel reported that "Sir Herbert Tree, as representing the dramatic profession, declared that he could not, and would not, countenance it" (Poel 230-31).

85The twentieth century: from spectacle to experimentation

Beerbohm Tree was a hard act to follow. One reason for the decline in stagings of King John may well have been a kind of "rain shadow" effect; the stage tradition had established that King John was a play that demanded spectacle, and it must have been clear for producers that they would not be able to out-do Tree's cast of hundreds. Intermittent productions in the early years of the twentieth century by F.R. Benson as part of a cycle of the complete Histories (1901, 1909, 1913, and 1916) followed, but tastes had changed, as a reviewer in the Birmingham Mail makes clear:

86Amongst all the plays of Shakespeare this is, perhaps, one of the least acceptable to modern audiences. There are great scenes and tragic episodes, but the atmosphere is too satiated with mediaeval barbarism to appeal strongly to an audience of the twentieth century. (April 29)

87The challenge offered by the work of Poel, and more widespread experimentation with methods of staging generally in the early twentieth century, will have added to this general dissatisfaction with an approach now considered old-fashioned. It is also probable that the decline in interest in King John was, in part, due to the long period of peace between the First and Second World Wars. It is a battle-ridden play, as well as an intensely political one. If Tree's production had reverberations of the Boer War, the Second World War was very much in the mind of audiences attending productions in the mid-century period. One review of the 1940 production by Andrew Leigh and B. Iden Payne makes clear the generally patriotic interpretation of the play; in striking support of the motivation of the producers in doing so, the review is interrupted by a prominent announcement, set off in a box from the text:

88The Bastard was the early champion of English unity

| BLACK-OUT 9.16 p.m. to 4.51 a.m. The Moon Rises 6:50 a.m.; sets 10.31 p.m. |

and took the field against Pope, Barons and even the King himself, to keep the English spirit high. (Times, 9 May 1940)

89The Birmingham Evening Dispatch also makes the obvious connection between the production's patriotic interpretation of the play and the contemporary crisis faced by the country. The reviewer quotes the Bastard's final lines:

90Come the three corners of the world in arms

And we shall shock them: naught shall make us rue,

If England to itself, do rest but true.

These lines which close "King John" have a topical air. There may be only one corner (with two others non-belligerents) against us at the moment, but Shakespeare's clarion cry is one which must find an answer to-day in the heart of every Englishman. (8 May, 1940)

91The ghost of Beerbohm Tree still stalked the production, however; the reviewer for the Birmingham Post commented that the actor for John, George Skillan, "by a coincidence of makeup looked very much like Sir Herbert Tree," while the Times reviewer commented on the continuing insistence on historical costuming: "Messrs. Iden Payne and Andrew Leigh have evolved the action in a series of handsome pictures bright with medieval blazonry."

92The following year, as the blitz raged in London, Tyrone Guthrie's 1941 production provoked one reviewer to point out an anachronistically appropriate line:

93"King John" is the second best war-time play in the language, and the Old Vic production last night at the New Theatre is a timely reminder of it. The play even contains the extremely apt line about "An airy devil in the sky who pours down mischief." [TLN 1286-7]

94Guthrie adopted a deliberately non-realistic staging technique. In marked contrast to Tree's habit of bringing horses on stage, Guthrie mounted his actors on hobby-horses. The review continues:

95Tyrone Guthrie has lightened the production--some of the battle scenes, in fact might be fitted into a revue . . . with their toy turrets and kings on prancing hoppy horses. (G.W. Bishop, 7 July, 1941)

96The costume design for the production gives some idea of the effect. Guthrie was, no doubt, working within a wartime budget that required minimalist staging, but he is also clearly responding to the general twentieth century movement in staging towards stylization and an emphasis on ensemble playing rather than a reliance on star performers; his influence was to become profoundly important in the development of the Stratford Festival, Ontario, of which he was founding director.

97While acting continued to stress characterization, and reviewers continued to praise or blame actors for the authenticity they brought to their parts, Guthrie's use of a staging that commented mockingly on the warring factions in the play is a sign that directors were bringing a new approach to their productions: a play was to be filtered through a specific directorial vision, a thematic interpretation of the play as a whole. This trend was certainly influenced by the writings of critics like G. Wilson Knight and the whole school of thematic critics who followed. King John lent itself to this mode of production, with the Bastard's crucial speech on Commodity a perfect starting point. In his 1945 production for the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, Peter Brook was among the first to dare to clarify Shakespeare's language for a modern audience. A young Paul Schoflield as the Bastard was assigned these lines:

98That smooth-faced gentleman expediency, or as they say

Commodity, the bias of the world,

The world, who of itself ispiezèdbalanced well . . .

(Prompt Book, emphasis indicating manuscript additions)

99Brook cut the play very little, despite his later justification of severe cuts to Shakespeare when he cheerfully remarked that "what we have removed is what is no longer necessary." Reviewers commented approvingly or disapprovingly on his choice to open the play with a scene which was either "designed to suggest the underlying weakness of a King who was strong only in seeking his immediate advantage" (H. W. Bush, Birmingham Gazette 7 October, 1945) or which left "an impression of fussiness, as when the first curtain opened on a bacchanal" (Birmingham Post October 16, 1945). If Beerbohm Tree introduced elaborate stage business (slicing off the heads of daisies) intended to underline his interpretation of John's character, Guthrie and Brook used costume and stage business to generate an interpretation of the play overall, and through it a commentary on current social issues. Interestingly enough, some stage business recalls the kind of providential intervention Shakespeare removed in his reworking of The Troublesome Reign where he transmuted the spectacle of the five moons appearing physically into an ambiguous report from the mouth of Hubert: Brook (following the earlier production in 1940 by Leigh and Payne) introduced stage thunder at the point when Arthur leaps from the wall of the castle. Nature comments offstage on human tragedy.

100Two sides of the Atlantic: tradition, stylization, satire

British performances of King John in the twentieth century have been extensively and insightfully discussed by Cousin and Hodgdon. On the other side of the Atlantic King John was first performed in 1738 in Philadelphia (Child lxxix), and it continued to hold the stage until the middle of the nineteenth century. Edwin Booth, older brother to the John Wilkes Booth who assassinated Lincoln, produced the play in 1973. Touring companies (notably that of Charles Kean) brought the play regulary to North America. One notable home-grown production was that of Robert Mantell, who performed the play in Chicago and New York in 1907-09. A review of this production by W Winter in the New York Tribune commentS that "The character of King John . . . is, of all his characters, one of the most difficult of authoritative, enthralling representation." Winter observes that the character of the king is revealed slowly to the audience; the opening scenes show him to be an "intrepid, resolute, expeditious warrior, not openly exhibiting either malevolence, weakness, or guile." But after Arthur is captured, John "suddenly reveals himself as a subtle, crafty, treacherous, sinister villain. . . . the author's revelation of him in this new light tends to bring with it a sense of discord, and to make the character seem anomalous." The reviewer's praise for the production as a whole is based on his perception that Mantell's performance, "from the beginning [interfused] malignity with royal arrogance, duplicity wiht irascible valor, and a lurking incertitude beneath an outside show of power."

101From the middle of the twentieth century, Shakespeare festivals sprang up in North America: initially at Ashland, Oregon, and Stratford, Ontario, then later in a remarkable proliferation of festivals and productions varying from largely amateur to major professional companies. Though some of the open-air performances may merit Irene Makaryk's somewhat dismissive comment, "The hallmark style of these productions is similar enthusiastic rushing about, playing comedy for its outrageousness and slapstick, tragedy for its melodrama," there is no question that these festivals have both generated an audience for Shakespeare and become increasingly inventive and polished in recent years. Many are recorded in the Internet Shakespeare Editions' database of Shakespeare in Performance. King John may not have been high on their list of plays, given the need to attract audiences with more well-known titles, but there were regular productions from 1948 (Oregon) onwards. Between about 1950 and 1980 there was a significant divergence between the UK and North America in attitudes to the play and directorial styles; in more recent years theatrical approaches have tended to converge as globalization becomes the norm.

102In the UK, audiences (or at least the reviewers) began both to discount the value of King John as a play, and to expect more directorial inventiveness; in North America the plays were fresh enough to their audiences that they could play them straight. James Sandoe, directing King John for the 1964 Colorado Shakespeare Festival, commented:

103We are playing the play uncut and without intermission and, at this point, it appears to be ten minutes more than a "two hours' traffic" for our stage. The stone seats in the Mary Rippon Theatre may challenge comfort but, as standing in the pit under an afternoon sun kept the groundlings attentive at the Globe, it seems safe to leave Shakespeare uninterruptedly to himself if, as rather a lot of people appear to believe, he is the playwright we admire 400 years later. (Program, "A Note About the Play")

104In contrast, reviews of the production at the Old Vic by Michael Bentall in 1953 were clearly impatient with the staging, constrained as it was by a permanent set also used for other plays, and costumes that were seen as a confusing mix of medieval and modern. Milton Shulman's review of the production was headlined "But WHY space suits in Shakespeare," and the details of the review are no more flattering:

105Vying with the bustling production to distract you from the words were the costumes by Motley. I can take with equanimity a Duke of Austria looking as if he as just lost a battle with a vacuum cleaner and a Cardinal wearing smoked glasses he had apparently picked up from a 3-D film, but medieval armies wearing uniforms that could only be fit for space ship travel is really making too unseemly a concession to the comic strips. (Evening Standard, 30 October 1953)

106The actual performances by Michael Hordern as King John, and Richard Burton as the Bastard, were admired. One interesting indication of a production still influenced by the hardships of war and its aftermath is the direction in the prompt book to the Bastard on the inflection of his final patriotic lines, indicating that they should be made conditional and admonitory rather than simply triumphant:

107Naught shall make us rue

If England to itself do rest but true.

(TLN 2728-89)

108This production marked a clear sign that the play was losing its interest in the UK; it was seen increasingly as second-rate, lacking the substance of the Richards and Henrys; the sagging reputation of the play is discussed further in the General Introduction.

109North American audiences were less critical -- and perhaps less jaded. By the mid sixties, the Stratford Festival had performed King John once (1960), and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival had performed cycles of all ten histories twice -- refreshingly, they seem to have been uninfluenced by the general critical focus on the eight plays of the two tetralogies. Although the audience demographic for both companies is generally similar, their origins make clear significant difference in the development of their staging. The Oregon Festival had very modest beginnings; its physical structure was, appropriately, based on a building erected for the deeply idealistic and democratic Chautauqua movement. Taking its name from Lake Chautauqua in western New York State where it began, the movement aimed to bring culture and adult education to rural America. It died out in the mid-nineteen-twenties, but the ruin of Ashland's building was still in place when Angus Bowmer, a young school teacher in Ashland, initiated the festival with performances of Twelfth Night and The Merchant of Venice in 1935. It was two decades later that the festival hired its first full-time employee. The Stratford Festival was also initiated at a grassroots level, but its aims were as much to boost the town's economy as to provide a platform for culture, and it began with a splash: the director, designer, and star actor were from the UK (Tyrone Guthrie, Tanya Moiseiwitsch, and Alec Guiness).

110What North American Shakespeare pioneered was a stage that was modeled more closely on Elizabethan structures, with a deeply thrust performance surface and minimal provision for scenery. The Oregon Elizabethan stage was first constructed in 1947, then rebuilt in 1959 and 1992. Stratford's stage was built in 1953, designed by Tanya Moiseiwitsch; it was housed at first in a tent, but three years later the Festival had sufficiently proved itself that the Playhouse was built around it. Both Oregon and Stratford provided three levels for acting, on the lines of the Globe (as it was thought to have been at the time), and both required a significant re-thinking of staging and stage practices.

111Stratford's first production of King John was in 1960. It was directed by the same Douglas Seale who three years earlier had staged the play at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. The close connection between Seale's two productions is symptomatic of the close relationship that was maintained between the Stratford Festival and UK production values. Reviews of the UK production mention admiringly the "mediaeval splendour of the costumes . . . [set] against a sombre background of castle and court" (J.C. Trewin, Birmingham Post, 17 April, 1957). The Stratford (Ontario) production seems to have been similar in intention, and again the costumes, this time designed by Tanya Moiseiwitsch, were praised for their splendour. Reviews varied from "dull" (Kingston Whig-Standard) to "colourful" (E.H. Lampard, St. Catherine Standard, June 28, 1960), but they single out the performance of a young Christopher Plummer -- one of many Canadian actors who made a name for themselves in Stratford -- in the role of the Bastard.

112By 1969 the Oregon Shakespeare Festival had began a third cycle through the history plays with their third production of King John. Despite the general atmosphere of experimentation in theatre and new approaches in criticism at the time, is clear that the historicist views of E.M.W. Tillyard were still largely unchallenged. The director, Edward Brubaker, summarized the play's attraction as having "all the virtues of good melodrama." He continued, stressing the importance of what he saw as the play's overall theme : "In one respect, however, King John surpasses the best of melodramas. It is grounded on a serious theme handled with intelligence and passion. The theme concerns the difficulty a usurper has in establishing peace and good order in his kingdom. . . . The moral of the play is as clear as its action is lively and spectacular. The king who acts justly need not fear. When he fears, he becomes tyrannical and loses the loyalty of his followers" (Program, "Director's Note"). As late as 1976, Ricky Weiser, directing the Colorado Shakespeare Festival production, stressed the play as inhabiting a distant past, the "age of myth and legend, art and romance, blood and death" ("Director's Notes").

113The England of the 1970s was far less nostalgic, far less accepting of a traditional historicist approach to just about anything. The mood was cocky, as London led the fashion world, and black comedy was the rage. King John was produced by the first woman director for the Royal Shakespeare Company, a twenty-three year old Buzz Goodbody. From the perspective that forty years provides, a modern reader will find the press comments of the time unselfconsciously sexist; Ian Woodward in the Sun clearly enjoyed his interview with her:

114Buzz Goodbody certainly boasts an apt surname. She's leggy, curvy, well-endowed in the right places.She's no ordinary girl, either. She's a pioneer in the doggedly male preserve of theatre director. . . .Quite a girl. During rehearsals for King John she smoked 40 cigarettes a day, ate peanut-butter with everything, and kept her sanity by listening to the Beatles, Judy Collins and Bob Dylan on a portable record-player. (9 June, 1970)

115Woodward comments that she was "discovered" by John Barton, then an associate director at the RSC. This association no doubt explains Goodbody's occasional "improvement" of Shakespeare, as she added a number of passages from The Troublesome Reign. In transmuting the play from its tradition of not-quite-tragedy to outright black comedy, Goodbody indirectly freed later directors from the duty of making John's death moving in the tradition of Beerbohm Tree. Goodbody's king was performed by a young Patrick Stewart; Benedict Nightingale, writing in The New Statesman described a death scene that was about as close to the opposite of Tree's as one can imagine:

116We see Stewart's John being pushed about (literally) by his mother, . . . we see him snickering, whooping, leaning, waving his feet at his courtiers, peeping at them through the golden lattice of his throne and, finally, sliding cross-eyed off it onto his bottom in the most farcical death-scene I can remember having seen. (19 June, 1970)

117Goodbody's King John was intended for touring schools and colleges, and its mischievous revaluation of the play can be understood both in terms of the irreverence of youthful culture that was a feature of the time, and a desire to reach a younger audience.

118Her mentor, John Barton, having decided apparently that King John was a deeply flawed play that needed major reconstruction to rescue it, carried on the process of adaptation begun by Goodbody. In pursuit of relevance -- the UK was in the midst of a period of political uncertainty with a hung parliament and high inflation -- he added large chunks of The Troublesome Reign, some passages from Kynge Johann, and passages of his own "Shakespearean" language; the result was the most thoroughgoing adaptation of the play since Cibber's Papal Tyranny. John Barber commented:

119The director, John Barton, has thought well to chop the text into messes and to interlard it with chunks from another Elizabethan play about John, and from a Medieval Morality. He has also added a plentiful helping of lines of his own.The result is a patriotic pageant about the state of England today, when (as Shakespeare never said) "The price of goods soars meteor-like to the heavens." (John Barber.Daily Telegraph, 21 March, 1974)

120Robert Cushman, reviewing the play in The Observer, picked up on the same line: "A meteor was a favourite Elizabethan image for over-reaching ambition, and on this occasion Mr. Barton has gone in for a certain amount of soaring himself." The headline for his review read "King Barton's 'John'" (24 March, 1974). Richard David (Shakespeare in the Theater 174ff) discusses Barton's production in detail. He points out that the three plays of King John vary radically in their approaches to the king and his reign, to the extent that they "directly contradict each other" (175); with epigrammatic insight he sums up the differences: "One could say that Bale's Morality was didactic, The Troublesome Reign historical, and Shakespeare's King John dramatic" (176).

121In the same year (1974), the Stratford Festival (Ontario) staged the play for the second time, once again led by an director from the UK: Peter Dews, who came from the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, and who had gained a strong reputation from his TV production of the history plays, An Age of Kings. In marked contrast to Barton's political interpretation, Dews seems to have avoided making the play pointedly relevant. In a comment that may be more American than Canadian, one reviewer remarked that "To his everlasting credit, director Peter Dews has resisted the temptation to corset the play in a facile Watergate analog. He searches for, and finds, universality rather than mere topicality" (Jay Carr, The Detroit News, 25 July, 1974). Perhaps because he was aware that his North American audience might be less schooled in Shakespeare than viewers in the UK, Dews freely modernized the language, substituting a more readily understandable vocabulary where he felt it necessary. In some cases he seems to have felt either that Shakespeare needed softening, or that his audience was far from literate, amending words and phrases that an actor can make quite clear without change: in the speech where the Citizen argues for the marriage between Blanche and Lewis, the phrase "If zealous love should go in search of virtue" becomes "If holy love . . ." (2.1, TLN 743; emphasis added).

122The last years of the twentieth century

As part of its project to film all of Shakespeare's plays, the BBC filmed King John for television in 1984. Perhaps because of a limited budget, the production avoided any attempt to use the film medium to create a sense of realism, as it used sets that were deliberately stagy, and there was no attempt to create filmic battle scenes. In keeping with the aim of the series to avoid controversial directorial intervention in the plays, it is a "fundamentally a conservative interpretation" of the play (Cousin 100). The television medium allows director David Giles to underplay the high rhetoric of many passages in the play, as his actors are able to speak lines in quiet intensity rather than the higher level required to project from the stage. This approach is allows George Costigan's Bastard to address the camera directly in closeup in his soliloquies, and accordingly he becomes more than ever the sympathetic center of the play. The women also benefit from this mode of understatement, especially a brilliant Claire Bloom as Constance, making the supposedly "mad" scenes bruisingly and movingly sane. The other women are also impressive, with Mary Morris's splendidly reptilian Eleanor and Janet Maw's surprisingly feisty Blanche. Leonard Rossiter portrays John as weak, vacillating, supercilious, and manipulative, more like a teenager than a king, by turns aggrandizing and sulky. Cousins's discussion of the stage history of King John in the Manchester University Press series on Shakespeare in Performance--mentioned frequently in this essay--reviews the BBC film and several other late twentieth century British productions in some detail.

123It is a measure of the now-marginal status of King John that on the rare occasions it was performed in this period it was relegated to smaller theaters. Deborah Warner directed it for the RSC in 1988 at the Other Place, and Robin Phillips for the Stratford Festival in the smaller Tom Patterson theatre. Like Goodbody and Barton before her, Warner saw King John as a morality play, peopled with almost parodic personalities; like them she emphasized the play's political satire:

124[T]his play . . . presents politics as a lethally stupid boy's game, showing every player outsmarting the others until even the smugly invincible Cardinal . . . delivers one fatwa too many. . . . On comes Nicholas Woodeson's John, a puny power maniac, ungraciously attired in greatcoat and pinstripe . . . blowing himself up like a bullfrog under the eye of his warlord mother.125Comes the siege of Angers, and the two armies go to it hammer and tongs with the city's spokesman sitting pretty on the walls, munching a sausage, and observing the battle like an exciting Centre Court match. (Irving Wardle, The Times, 4 May, 1988)

126Warner's production was about as far from the operatic, cinematic lushness of a Beerbohm Tree as it was possible to get: the stage was minimalist, and the text was performed virtually without cuts. The only striking feature of the set -- severely limited by the space in the Other Place -- was a large number of ladders variously arranged to suggest the acting spaces the play requires. If "commodity" added up to nothing more than a rather nasty game, perhaps the stage set was in part designed to suggest snakes and ladders, with the human power-brokers the snakes.

127While Warner's production was minimalist in its staging, it is important to realize that any modern production has access to far more sophisticated lighting and sound effects than were available in the age of spectacular productions. Changes in technology are almost transparent to the audience, with the result that we take for granted kinds of spectacle that were unavailable to an earlier director. Robin Phillips provided a brilliant example of effective use of modern technology in his 1993 production on the small, deeply thrust stage at the Tom Patterson theater in Stratford Ontario. H.J. Kirchhoff, writing in the Globe and Mail, reported that

128Phillips mikes whispered conversations and asides to produce eerily amplified reverberations which, with subtle use of lighting, gives them a sharply different flavour from more conventional dialogue. The scene in which John quietly suggests to his man Hubert . . . that he kill the captive Arthur -- "a very serpent in my way" -- is hair-raising, as is the later scene, whispered in semi-darkness, when Arthur successfully begs Hubert not to kill him. (3 June, 1993)

129Kirchhoff was sufficiently impressed by this production that he comments on the play that "it's hard to imagine why [it] is so lightly regarded and seldom performed."

130In a move increasingly common in more recent years, Phillips set the play in a not-quite-modern period. The effect is to make the play seem less a product of a now-alien culture, without introducing potentially jarring anachronisms:

131By altering the period in which it is set – no great loss considering the playwright's cavalier commitment to historical veracity – Phillips has transformed it from a tedious tale of petty kings feuding over the spoils of a tottering Britain, to a riveting dissertation on self interest and self service. By setting it in the Edwardian era, . . . he downplays its macho battling to highlight the duplicity that oozes from virtually every wretched character in the tale. (John Coulbourn, Toronto Sun 2 June, 1993)

132The twenty-first century

Coming in the last decade of the twentieth century, Phillips's production found an approach that may explain why King John has been more frequently performed in the early years of the twenty-first. Writing in the New York Times, Ben Brantley commented that "'King John' . . . has vital resonance for an age that often sees its politicians less as monsters than mediocrities, distanced from greatness by all-too-pedestrian frailties." The Edwardian setting put the play in the period when Ibsen and Shaw were using the stage as a way of exploring social issues; King John is certainly amenable to a treatment that makes it more a "problem" play of this kind than a history play dealing with far-off times. (The whole question of the play's genre is dealt with in more detail in the [[link]] General Introduction).

133In the first decade of the millennium, there has been a flurry of productions in both the UK and North America. Settings for the play varied from medieval to modern, but all, in one way or another, presented the play as a statement on current politics, and many realized the potential for darkly comic moments in the play.

134Michael Billington reviewing two separate productions in the UK emphasized the political power of the play as highlighted by both directors:

What startles one is the play's modernity: it accords with our own scepticism about power politics. But, far from being a patriotic battle-hymn, the play is, especially in the first half, a corrosively satiric study of sordid power struggles. (On Gregory Doran's 2001 production, Guardian, 8 March, 2001)This is a cynic's view of medieval English history in which virtually no man is a good as his word. . . . There's a great moment when the Bastard announces that warlike John is ready "to feast upon whole thousands of the French" and we suddenly see the frail, sickening king tottering about in his nightgown. (On 2006 Josie Rourke's 2006 version Theatre Record, 26 August, 2006)

135In a response that is almost universal in recent years, again reviewers were struck by the play's relevance to current events: