Introduction

1An experimental play

King John is a play that constantly surprises--and occasionally frustrates--expectation. It offers the audience scenes of high emotion and of dramatic debate, but it is not easy to categorize the overall effect or appeal. Its isolation in period from the other history plays means that critics look in vain for the prophetic sweep of those plays comfortably located within the larger narratives explored in the two tetralogies. If the play is approached as a tragedy, the protagonist, King John, is likely to disappoint, as he shares the stage with several other significant characters and fades into weakness as the action progresses; in addition, his death is never shown to be clearly or directly the result of his own actions. Nor is the play in any sense a comedy, though the Bastard has his moments of witty commentary. Partly because of this uncertainty of expectation, King John has been characterized as a "transitional" play, fitting neatly between the two tetralogies (Vaughn). The concept of two tetralogies is deeply engrained in critical studies of the histories, despite the remarkable lack of evidence that Shakespeare thought of his historical dramas in this way. As I discuss in my Textual Introduction, the three plays on Henry VI, followed by Richard III, might have some claim to have been conceived as a sequence since they share so many characters, and some structural characteristics, but even the Henry VI plays seem not to have been composed in chronological order, and the title page of the first version of Henry VI, Part Three suggests that it is the second part of a two-part play--a much more common authorial strategy. Similarly, the two parts of Henry IV and Henry V work well as a sequence of three, with the first two explicitly linked. Richard II, however, is a clear outlier, with its deeply poetic language, its focus on one central character--despite the structural importance of Bolingbroke--and its carefully focused, single plot. If King John is to be seen as a transition it is at least as likely that it was written between Richard II and Henry IV, Part One. Like Richard II it is composed entirely in verse; like Henry IV, Part One, it features a fictional character as one of the major sources of entertainment and commentary on the historical plot.

2There is nonetheless some insight in the approach that sees King John as a transitional play. The term suggests experiment, as the author moves from one mode of writing to a different one; if at times King John challenges and frustrates our expectations, it is in part because it is experimental. Whatever its exact date of composition, the mid-1590s was a period when Shakespeare seems to have been constantly exploring a remarkable range of genres and sources for the plays he was writing: Love's Labor's Lost (comedy of manners and words with a non-comic ending), Romeo and Juliet (domestic tragedy with a comic structure), Richard II (history, with an elevated, almost epic style), and A Midsummer Night's Dream (multi-layered comedy like nothing before or since). There are, of course, many similarities within this group of plays: all seem at times drunken with language; three are preoccupied with young love, two explore metatheater in plays-within-plays. The scene in King John where the Citizens look on the battles of the antagonists comes close to the same kind of metatheatrical structure. The Bastard wittily points this out:

By heaven, these scroyles of Angiers flout you, kings,

And stand securely on their battlements,

As in a theater, whence they gape and point

At your industrious scenes and acts of death.

(TLN 687-90)

But the differences between these plays are even more remarkable, whether we look at genre or structure.

3Shakespearean criticism has been profoundly influenced by the choices his fellow actors, Heminges and Condell, made as they organized the bundle of plays they were preparing for publication by genre, choosing comedies, histories, and tragedies. We are now acutely aware that the their three genres were a compromise. The late arrival of Troilus and Cressida, for example, forced the printer to sandwich the play between the histories and tragedies. This is not a bad place for it, we might think, but the inclusion of Cymbeline among the tragedies is a clear sign that the pattern they saw was somewhat blurry. So too is the cross-categorization of Richard II from the quarto's Tragedie of King Richard the Second to a history in the Folio, and Lear from the quarto's True Chronicle Historie of the life and death of King Lear and his three Daughters to the Folio's tragedy. More recent critical approaches have refined the threefold pattern of the Folio to include convenient categories for at least two of its anomalies, as Troilus and Cressida is slotted into the group of "problem plays" and Cymbeline into the group of late "romances."

4But what all these decisions, from Heminge and Condell onward, tend to do is to smooth over the extraordinary angularity and variety of the work that Shakespeare has left us. Even within traditional genres no two plays look alike: in the tragedies, for example, we move from the tight construction of Macbeth with its central anti-hero to the sprawling dual plot of King Lear (in both versions); and no theory of dual authorship in the surviving version of Macbeth or of extensive revision in King Lear will paper over the differences. If we choose to create a subcategory for Roman tragedies, we are similarly left with the chasm between the restrained language and compact structure of Julius Caesar and the sprawling riches of Antony and Cleopatra, with its episodic structure and dense imagery. There are, of course, overarching changes in Shakespeare's craft between early and late plays, but at the granular level as we look at groups of plays we are left with variety rather than regularity and consistency; with experimentation as much as with anything we might label "genre," or "development."

5Thus experiment in Shakespeare tends to be the norm rather than the exception. As late as the final group of four romances, Shakespeare seems always to be creating and exploiting new and unexpected dramatic structures; even so consummate a work of art as The Winter's Tale has some instructive similarities with King John: both plays seem rather loose in construction, with unanswered questions about the details of the plot, a shift in mood and mode around the middle of the play, and an unanticipated ending--the revival of the statue of Hermione in The Winter's Tale, and the sudden, hitherto unannounced appearance of the legitimate heir to the throne, Prince Henry, in King John. Other similarly divided, experimental, fascinating, and loosely constructed plays come to mind: Measure for Measure, and the collaborative Pericles, for example. Their recent critical and performance histories suggest that these plays, like King John, are the more interesting for being untidy and unpredictable.

6It may seem counter-intuitive to suggest that a play in which Shakespeare so wholeheartedly adopted the framework of the earlier play, The Troublesome Reign of King John (TRKJ), should be categorized as experimental. The closeness to the earlier play in construction (though not at all in language) has tended to embarrass critics concerned to see Shakespeare as always the most original of playwrights. But a comparison between TRKJ and King John that looks beyond plot reveals that Shakespeare's play is exploratory, and engages in a kind of meta-debate with its source. Even in its adaptation of the structure of the earlier play, some of the moments that are sometimes seen as ways in which Shakespeare is less careful than the author of The Troublesome Reign may be re-thought as experiments in the kind of dramatic shorthand that appears in later plays. Shakespeare's characters in his later plays tend to reveal their inner lives through language more than through their response to explicit external motivation; the jealousy of Leontes is a well-explored example where Shakespeare provides none of the careful explanations that appear in his source, Pandosto. In a similar fashion, in Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare never makes obvious the reason for Antony's crucial choice to fight Caesar by sea; his source, Plutarch, didactically blames Cleopatra, but Shakespeare's play leaves the audience to connect the dots as Antony simply blusters in justification of the decision (Ant TLN 1892ff).

7A similar shorthand is at work in King John on a number of occasions where The Troublesome Reign is more explicit. In Shakespeare, the warrant for Arthur's death becomes, without explanation, an order for Hubert to put out the child's eyes; in TRKJ the change is made explicit where the warrant is ![]() read out, making it clear that John has mitigated the sentence of death to blinding. There is a similar blurring of motivation in the way the two plays record the death of King John. In TRKJ, it is closely linked to his actions in ordering the plundering of the monasteries, as a monk, supported by his abbot, openly schemes against him in an extended scene; in King John Hubert breaks the news to the Bastard that the king has been poisoned by a monk, but hazards no motivation for it, and the monks never appear on stage. Kenneth Muir (78-85), Ernst Honigmann (lvii ff.), A. R. Braunmuller (4 ff.) and Charles Forker (79 ff. and throughout his commentary) discuss other occasions where TRKJ makes explicit what King John leaves implied, or refers to in passing: most notably the spectacle in the actual appearance of the five moons (TLN 1906; compare TRKJ TLN 1749), John's second coronation (TRKJ TLN 1701), the greater stage presence of the prophet Peter, and the dramatization of the double (for)swearing of the French lords (TRKJ TLN 2474, 2540).

read out, making it clear that John has mitigated the sentence of death to blinding. There is a similar blurring of motivation in the way the two plays record the death of King John. In TRKJ, it is closely linked to his actions in ordering the plundering of the monasteries, as a monk, supported by his abbot, openly schemes against him in an extended scene; in King John Hubert breaks the news to the Bastard that the king has been poisoned by a monk, but hazards no motivation for it, and the monks never appear on stage. Kenneth Muir (78-85), Ernst Honigmann (lvii ff.), A. R. Braunmuller (4 ff.) and Charles Forker (79 ff. and throughout his commentary) discuss other occasions where TRKJ makes explicit what King John leaves implied, or refers to in passing: most notably the spectacle in the actual appearance of the five moons (TLN 1906; compare TRKJ TLN 1749), John's second coronation (TRKJ TLN 1701), the greater stage presence of the prophet Peter, and the dramatization of the double (for)swearing of the French lords (TRKJ TLN 2474, 2540).

8There is a similar economy of dramatic expression in the way Shakespeare simplified what is at times overdetermined motivation of character in The Troublesome Reign. In TRKJ the Bastard is given multiple reasons for his hatred of Austria--he is responding both to the fact that Austria killed the Bastard's newly acknowledged father, Richard Coeur-de-lion, and to the prompting of Blanche, who is clearly attracted to him:

Blanch Well may the world speak of his knightly valor,

That wins this hide to wear a Ladies favor.

Bastard Ill may I thrive, and nothing brook with me,

If shortly I present it not to thee.

(TRKJ TLN 594-7)

Some trace of this moment may survive in Blanche's comment in King John--

BLANCHE

O, well did he become that lion's robe

That did disrobe the lion of that robe.

(TLN 441-2)

--but Shakespeare's Bastard focuses on a single motivation, that Austria killed his father, ignoring her interruption.

9The Troublesome Reign reign radically compresses history in order to create coherent drama from the scattered and episodic historical events the chronicles record; Shakespeare further condenses the plot, paradoxically making the play more like what we now understand of the contingent nature of the historical record in all its ambiguity. As the comparison between King John and later plays like Antony and Cleopatra or The Winter's Tale makes clear, Shakespeare learned to trust his actors and his audience to fill the spaces between the words, both in plot and character, in the process forging a suggestive and creative ambiguity that has made his plays available for reinterpretation in contexts far removed from his own. If the structure of King John, so closely linked to The Troublesome Reign, nonetheless reveals signs of Shakespeare's experimentation, two features of the play more strikingly illustrate his exploration of dramatic effect: the emphasis on scenes of intense emotion, and on debates that explore issues both on political and personal levels.

10Emotion

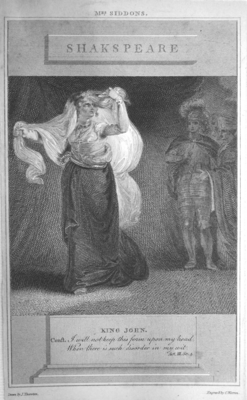

Nineteenth-century interest in the play was in significant measure driven by the way the role of Constance provided a splendid opportunity for the major actresses of the day to showcase their skills and evoke sympathy from the audience. Theater reviews discussed the relative merits of the interpretations by Mrs. Siddons, Helen Faucit, and others. A modern audience may be more impatient with Constance's outbursts, but her evocation of grief at Arthur's fate remains enormously powerful:

PANDULPH

You hold too heinous a respect of grief.

CONSTANCE

He talks to me that never had a son.

KING PHILIP

You are as fond of grief as of your child.

CONSTANCE

Grief fills the room up of my absent child:

Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me,

Puts on his pretty looks, repeats his words,

Remembers me of all his gracious parts,

Stuffs out his vacant garments with his form.

Then have I reason to be fond of grief?

(TLN 1475-83)

11The speech is sufficiently moving that earlier critics speculated that it was written by Shakespeare in response to the loss of his son, Hamnet, in 1596, though the play is generally dated somewhat earlier. In passages like this, Shakespeare comes close to the precept spoken (then immediately broken) by Berowne in Love's Labor's Lost: "Honest plain words best pierce the ear of grief" (LLL TLN 2711). More important than conjectures about Shakespeare's motivation in writing these speeches for Constance, however, is the way that they form part of a wider pattern in the play, where characters are given ample space to express strong emotion. Critics in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries tended to be rather embarrassed by the scenes of conflict between Constance and Eleanor, where the women take center stage in passionate verbal battles, perhaps because their naked emotion seemed to obscure the masculine business of political negotiation.

12Even the cameo parts of Lady Faulconbridge and Blanche stress strong emotion. Lady Faulconbridge begins in anger as she chides her son on attacking her honor, and ends in shame as she admits her adulterous relationship with Coeur-de-Lion. Blanche, whose early speeches project, on the whole, a conventionally obedient daughter, becomes for a moment the center of the rapidly centrifugal forces driving the English and French forces apart as she and Constance take center stage in a kind of competitive kneeling battle before Lewis (TLN 1232-49). Moments later, when King Philip of France releases the hand of King John and breaks off the brief alliance between the kings is broken, Blanche graphically represents and articulates the collateral damage of war:

The Sun's o'ercast with blood. Fair day adieu.

Which is the side that I must go withal?

I am with both; each army hath a hand,

And in their rage, I having hold of both,

They whirl asunder and dismember me.

(TLN 1260-4)

13The powerful emotion evoked by this visceral image of dismemberment becomes even stronger in the powerful scene where Hubert threatens to carry out King John's order to put Arthur's eyes out. In TRKJ, Arthur--who is clearly older than in Shakespeare's version--argues with Hubert on the level of ideas: that Hubert's soul will be lost by committing such a grievous sin, and that a subject is not bound to carry out a sinful order from his king. Shakespeare's Arthur plays on Hubert's feelings, emphasizing his love for his keeper: "When your head did but ache, / I knit my handkerchief about your brows." The effect is heightened by a moment of childish pride as he boasts that a princess embroidered the handkerchief--"The best I had, a princess wrought it me" (TLN 1617-19). The scene as a whole is a tour-de-force of dramatic pathos as Arthur pleads, often with precociously adult figures of speech, for his freedom from binding and blinding (see my discussion of Arthur's character, below).

14Emotion in the earlier scenes in the play is the province of the female characters, and to a large extent is generated by an articulate awareness of their own powerlessness. Arthur's predicament is a further extension of this dramatic mode after the three women have disappeared from the action. His later death offers the men in the play an opportunity to express a more masculine emotion, compassion, from positions of relative power. To my ears, however, the earls Salisbury and Pembroke indulge in self-serving hyperbole in order to justify their betrayal of the English cause:

SALISBURY

This is the very top,

The height, the crest, or crest unto the crest

Of murder's arms. This is the bloodiest shame,

The wildest savagery, the vilest stroke

That ever wall-eyed wrath, or staring rage

Presented to the tears of soft remorse.

PEMBROKE

All murders past do stand excused in this.

And this, so sole and so unmatchable,

Shall give a holiness, a purity,

To the yet unbegotten sin of times.

(TLN 2044-55)

The Bastard's less emotional, more measured and careful response

It is a damnèd, and a bloody work,

The graceless action of a heavy hand--

If that it be the work of any hand.

(TLN 2056-8)

is brushed aside as the lords prepare to meet with the forces of the Dauphin. Later in the scene, however, the Bastard reveals a deeper emotion than the lords, as he confesses that he no longer possesses his earlier confident assumption that he could understand and control the world around him:

I am amazed methinks, and lose my way

Among the thorns and dangers of this world.

15As Hubert lifts the lifeless body of the young Arthur, the Bastard meditates on the corruption of the state that has led to this moment, revealing an unexpected belief in the genuineness of the claim that Arthur had to the crown:

How easy dost thou take all England up!

From forth this morsel of dead royalty

The life, the right, and truth of all this realm

Is fled to heaven . . .

And in a graphic image he describes the savage scavenging for scraps of power unleashed by the dogs of war:

England now is left

To tug and scamble, and to part by th'teeth

The unowed interest of proud-swelling state.

Now for the bare-picked bone of majesty

Doth dogged war bristle his angry crest

And snarleth in the gentle eyes of peace.

(TLN 2145-55)

At this moment, both emotion and the analysis of power--the subject of many debates in the play--meet.

16In contrast to the Bastard's keen awareness of the moral issues he faces, King John becomes less concerned with major issues. His final moments are subdued and focus on his personal suffering. The preparation for his last entry on stage treads a fine line between pathos and comedy as Pembroke describes an ailing king, singing in his delirium. John's death is seemingly arbitrary, since Shakespeare makes no direct connection between the King's earlier order to sack the monasteries and the offstage actions of the monk who poisons him. John's final speeches make no mention of the wider debates and issues the play explores. He expresses little regret, and his lament as king is only that his political power is useless in combatting his fever:

. . . none of you will bid the winter come

To thrust his icy fingers in my maw,

Nor let my kingdom's rivers take their course

Through my burned bosom.

(TLN 2644-7)

17As in Constance's laments and Arthur's pleadings, Shakespeare concentrates on the emotional appeal of John's suffering and his sense of his own insignificance:

There is so hot a summer in my bosom

That all my bowels crumble up to dust.

I am a scribbled form drawn with a pen

Upon a parchment, and against this fire

Do I shrink up.

(TLN 2637-41)

The image of King John shrinking to a charred ember is apposite. His end gives little sense of the broader sweep of tragedy of the kind Shakespeare creates in Richard II, where Richard's death comes after an intense meditation on the nature of power, time, and pride, and he is given a moment of fierce triumph as he dies fighting. John's death is one of almost childish pathos, as he lies, aware of his own lack of power, and seemingly uncaring about the future. Nonetheless, John's death, in the hands of a good actor, can move an audience deeply; a reviewer of Beerbohm Tree's production in 1899 commented that "the stark backward loll of the corpse sent a tremour through the house." The arbitrary nature of King John's death recalls an older kind of tragedy, the simple turning of Fortune's wheel as the king becomes a "module of confounded royalty" (TLN 2668). Prince Henry picks up the image in this de casibus tradition:

Even so must I run on, and even so stop.

What surety of the world, what hope, what stay,

When this was now a king, and now is clay?

(TLN 2677-9)

18Since Henry is able only to respond "with tears" (TLN 2720), it is left to the Bastard to make a final emotional appeal to unity and patriotism. The final lines of the play, with their combination of emotion and patriotism, neatly sum up the appeal of the play to nineteenth-century directors and audiences. Eugene Waith suggests that twentieth century critical approaches have obscured the strengths that earlier productions found:

In the case of King John it may be that the tendency to look first for a pattern of ideas has kept us from understanding the power that critics once found in scene after scene. Perhaps if we are willing to alter somewhat the expectation we have cultivated, we too can feel that power (211).

19Waith's caution is salutary in reminding us of the sheer stageworthiness of many scenes in King John that dramatize the strong emotions of the characters. But it is also true substantial sections of the play, especially in the earlier scenes, are taken up with patterns of ideas: extended onstage debates on the value of legitimacy, on the uses of political power, and on the consequences of making and breaking oaths and loyalties. It is also true that the two earlier plays on King John (Bale's Kynge Johann [[ Invalid view ]] and TRKJ [[ Invalid view ]]) were explicitly plays of ideas, where the debates centered on the abuse of religion and the struggle that King John had against the church.

20Debates

After almost a century of sporadic interest in the play, the late twentieth century and early twenty-first have brought more critical attention to the play's overt exploration of politics. Andrew Rawnsley in the program notes to the Royal Shakespeare Company production of King John, 2012, comments on parallels between the play and contemporary current and past Prime Ministers of Great Britain:

21Here is a man without a popular mandate trying to impose himself on a riven kingdom at a time of austerity. This may remind us somewhat of David Cameron. Here is a man who lives resentfully in the shadow of a charismatic, crusading predecessor who spent much of his time on foreign adventures. This may remind us quite a lot of Gordon Brown. . . . The occupational hazards of power in 13th century England are not so very different to those now. Modern leaders must contend with formidable forces shaking the throne. Today's barons are international financial markets, media moguls, multinational corporations and other vested interests.

22Where there is politics there is argument. Ernst Honigmann observed that "In a sense, [King] John develops into one continuous debate, broken up into separate issues" (lxv).The opening scene of King John begins with a debate fierce enough to be called a confrontation when Chatillon attacks John's legitimacy as king of England. The scene ends with a genial echo of the same issue as Philip Faulconbridge accepts his illegitimacy as the bastard son of Richard Coeur-de-lion. In the dispute between Philip and his younger--but true-born--brother, the decision that King John reaches is somewhat unexpected; in the eyes of the law the question of legitimacy is irrelevant in deciding issues concerning property. All that matters is whether the child was born before or after the mother was married. Thus the Bastard freely chooses to give up his rightful inheritance and to follow the King and Queen Eleanor:

A foot of honor better than I was,

But many a many foot of land the worse.

(TLN 191-2)

23The importance of legitimacy in claims to the throne was very much in the air at the time King John was written. Walter Cohen (1016) and Ernst Honigmann (xxix) discuss the resonance within the play with the fact that Queen Elizabeth had been declared both illegitimate and legitimate by acts of Parliament. But in comparison with TRKJ it is striking that Shakespeare chooses not to focus the debate on the legal validity of John's claim to the throne; historically, and in TRKJ, John had a justifiable claim to the throne through his older brother's will, but in Shakespeare's play Eleanor makes very clear that John is a usurper:

KING JOHN

Our strong possession and our right for us.

QUEEN ELEANOR

[Aside to John] Your strong possession much more than your right,

(TLN 45-7)

24As a result, once again the debate is less on the question of legitimacy--since in Shakespeare's configuration of John's claim he has none--than on the value accorded legitimacy in the political maneuverings he faces. Shakespeare creates this debate in sharp distinction from his sources: in making King John a kind of proto-Henry VIII in his defiance of the pope, TRKJ does not suggest that King John is a usurper; and as long ago as 1874, Richard Simpson observed the degree to which Shakespeare reshaped the historical record to suit his exploration of King John as power-seeker:

The grounds of the doubt [about King John's fitness to rule] are not, as in the Chronicles, the general villainy of the King, his cruelty, debauchery effeminacy, falsehood, extravagance, exactions, and general insufficiency, but two points which do not seem to have weighed a scruple in the minds of John's barons -- the defect of his title as against the son of his elder brother, and his supposed murder of that son. The historical quarrel against John as a tyrant is changed into a mythical one against him as a usurper, aggravated by his murder of the right heir.

Richard Simpson (207).

25Shakespeare makes clear that John's claim to England rests on possession--on power--alone, and in the process he moves the debate from the conventionally ordered world of TRKJ to what we might see as a more modern, shifting world of politics and power. Ideologically, the play is closer to the uncertainties that lie behind the struggles in the three plays on Henry IV/V than either TRKJ or even perhaps to Shakespeare's own Richard II.

26In the second act of the play the two kings dispute rival claims before the city of Angiers, with the Citizen acting as a kind of adjudicator. King John flatly bases his claim on possession ("Doth not the crown of England, prove the king?" [TLN 580]), while King Philip takes the high road of principle, arguing the moral imperative of primogeniture. His righteous rhetoric, however, is proven to be hollow as soon as he sees a way of profiting more easily from the political solution offered by the Citizen. It is after this betrayal of principle that the Bastard realizes the naivety of his earlier cocky belief in his understanding of the world of the court, in his justly-famed soliloquy on political self-interest and the eclipse of honor and chivalry. He has just watched as Lewis invoked idealistic Petrarchan language in flattering Blanche, at the same time agreeing to a hastily-arranged marriage of great profitability; and he has just witnessed King John trade most of his provinces in France for peace. In the same spirit, King Philip, "Whom zeal and charity brought to the field / As God's own soldier" (TLN 885-6), rapidly made friends with his erstwhile enemy. Having failed in his earlier attempt to become involved directly in the action by persuading the kings to act as temporary allies on the field in order to bend their "sharpest deeds of malice" (TLN 694) on Angiers together, the Bastard resumes his role as chorus as he watches King Philip yield to

. . . that same purpose-changer, that sly devil,

That broker, that still breaks the pate of faith,

That daily break-vow, he that wins of all,

Of kings, of beggars, old men, young men, maids--

Who having no external thing to lose

But the word "maid"--cheats the poor maid of that;

That smooth-faced gentleman, tickling Commodity.

(TLN 889-94)

27Commodity, "the bias of the world" (TLN 895), is usually glossed as "political expediency" (see OED 2.b), but it is clear that it also includes the more modern concept of commerce (OED 2.c, d), especially since the Bastard concludes his soliloquy with the cynical determination to seek his own selfish profit: "Gain be my lord, for I will worship thee" (TLN 919). Some commentators have found this vaunt inconsistent, since the Bastard does not in fact pursue self-interest later in the play and ultimately yields his power to the rightful heir to the throne, but, as I shall explore later in my discussion of the Bastard as a character, this is to ignore the overall process of learning that the Bastard undertakes in the play. Instead, largely through the Bastard, the debate concerning the value of legitimacy in power politics is broadened to explore wider questions of the complexity of determining genuinely moral action in a world of conflicting loyalties. The Bastard internalizes the debate, as he begins by choosing honor over land, is then disillusioned by the craven bargaining of the two kings, and later follows unquestioningly John's command to raid the monasteries--a command that is not shown to be driven by any kind of principle, even for an audience that would have been predominantly anti-Catholic:

KING JOHN

[To the Bastard] Cousin, away for England, haste before,

And ere our coming see thou shake the bags

Of hoarding abbots; imprisoned angels

Set at liberty. The fat ribs of peace

Must by the hungry now be fed upon.

Use our commission in his utmost force.

BASTARD

Bell, book, and candle shall not drive me back

When gold and silver becks me to come on.

(TLN 1305-11)

28At this point the Bastard has moved from the position of choric commentator to an active agent in the grubby affairs of state he earlier mocked. It is not until he is confronted with Arthur's body that he returns to his role as commentator, in the passage (quoted above) where he describes graphically the destructive effects of the "dogged war" foisted on peace by "proud-swelling state" (TLN 2147-55). The Bastard's rather eager response to John's commission to raid the monasteries may be motivated in part by the fact that he has so recently watched the legate, Pandulph, join the ranks of those who use power in the service of Commodity. In a muted echo of the strident anti-Catholicism of TRKJ, King John has specifically accused the Pope of seeking to "tithe or toll in [his] dominions" (TLN 1081), making clear his belief that the quarrel over Stephen Langton's appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury is more about money--commodity--than spiritual matters.

29John's defiance at this moment in King John is the one place where some of the virulent anti-Catholic rhetoric of The Troublesome Reign surfaces. In the meta-debate between the two plays, it is clear that Shakespeare substantially tones down anti-Catholic satire. Shakespeare's play preserves intact something of the re-imagining of King John as a proto-protestant martyr that is suggested in the Homily Against Disobedience and Wilful Rebellion and in Foxe's Book of Martyrs; at the same time, the subtle and menacing character he creates in Pandulph is profoundly unflattering to the Catholic church and its focus on politics and material gain. Pandulph's presence in the play is limited to his political manipulation of those he interacts with; there is no reference to his spiritual office, other than the means it gives him to force obedience through the threat of excommunication. In the recent discussion about the nature of Shakespeare's religious beliefs, John Cox provides a cogent summary: "It is simpler . . . to assume that the writing in the plays and poems is consistent with the layered faith that was characteristic of the mainstream of Elizabethan religious life than to assume that the playwright was formed by one extreme, which he then gave up" (555). King John provides strong support for this position.

30Pandulph's political use of religion introduces a related debate, on the value of oaths. Although King Philip has made a solemn oath of alliance with King John, apparently cemented by marriage, Pandulph argues that his prior, general oath to uphold the Church takes precedence. The language Shakespeare gives Pandulph is intricate and legalistic, and the audience (including the Bastard) will be very much aware of the irony that lies behind his argument: he is using Philip as a means to force John to surrender power, and profit, from the English church. Philip's prior oath is being used as a lever in the service of commodity. The staging of the scene, where it is made clear that the kings are holding hands as a symbol of their alliance, gives a strong visual signal, especially at the time when Philip lets go John's hand:

PANDULPH

I will denounce a curse upon his head.

KING PHILIP

Thou shalt not need. England, I will fall from thee.

(TLN 1252-3)

31In staging the scene, it is less obvious when the kings should initially take hands. Philip's earlier appeal to Pandulph makes clear that already the two kings are visually, as well as figuratively, demonstrating their alliance. The visual image is reminiscent of a bridal pair--like Lewis and Blanche--taking hands as they leave the altar after sharing their vows, a parallel that Philip makes explicit:

This royal hand and mine are newly knit,

And the conjunction of our inward souls

Married in league, coupled, and linked together

With all religious strength of sacred vows.

. . . . .

And shall these hands, so lately purged of blood,

So newly joined in love, so strong in both,

Unyoke this seizure and this kind regreet?

Play fast and loose with faith?

. . . [shall we] on the marriage bed

Of smiling peace to march a bloody host,

And make a riot on the gentle brow

Of true sincerity?

(TLN 1158-79)

32Philip does his best to dodge the issue when he tries to separate the symbol from its underlying meaning: "I may disjoin my hand, but not my faith" (TLN 1193), but Pandulph is too seasoned a casuist to be deflected, and his response to Philip is both relentlessly logical and threatening as he forces him to renounce his vow to John.

33Oaths trump oaths, vows supersede vows. Constance justifiably claims that King Philip has "beguiled" her with a "counterfeit / Resembling majesty" (TLN 1025-6). When King John suborns Hubert to kill Arthur, Hubert at first swears to do John's bidding by putting out the eyes of the young prince, but later recants and also breaks his vow--though this time the audience will be relieved rather than disappointed:

Well, see to live. I will not touch thine eye

For all the treasure that thine uncle owes.

Yet am I sworn, and I did purpose, boy,

With this same very iron to burn them out.

(TLN 1701-4)

34And there is a series of interconnected and broken vows by the English and French lords: the English break their vows of allegiance to John to join the French forces; Lewis, in a remarkable display of ingenious duplicity, vows first to support them, then to slaughter them after the battle. In the words of the repentant Melun,

Thus hath he sworn,

And I with him, and many more with me,

Upon the Altar at Saint Edmondsbury,

Even on that altar, where we swore to you

Dear amity and everlasting love.

(TLN 2478-82)

Finally, the English lords, thus warned, break their oaths to Lewis in order to "untread the steps of damnèd flight" (TLN 2513) and return to King John.

35The trajectories of the debates on the significance of legitimacy and oaths seems to converge on a pessimistic assessment that these virtues are for sale, and will be used as a convenient cover to justify actions after the event. In his passionate defense of his actions to Lewis, Salisbury explicitly justifies the disloyalty of the lords to King John by claiming that only by doing wrong can one heal the disease within the land:

such is the infection of the time

That, for the health and physic of our right,

We cannot deal but with the very hand

Of stern injustice, and confusèd wrong.

(TLN 2271-4)

36Much the same can be said of the lessons Lewis earlier learns from Pandulph, who educates him in the art of rationalization as he shows how to claim the English throne in the name of virtue. Telling Lewis that he is "youthful," "green," and "fresh in this old world" (TLN 1510, 1531), Pandulph "speak[s] with a prophetic spirit" (TLN 1511), foreseeing the fears of King John and the superstitions of his subjects. Much of what he foretells is perceptive and turns out to be accurate; what he does not anticipate, however, is that Lewis will learn so rapidly to marshal argument in favor of breaking faith with the Church in the interest of his own gain, refusing to call off his successful invasion of England (TLN 2342-8). Pandulph is confident in his power:

. . . even the breath of what I mean to speak

Shall blow each dust, each straw, each little rub

Out of the path which shall directly lead

Thy foot to England's throne.

(TLN 1512-15)

But it is soon shown by Lewis to be limited and temporary, easily overcome by others wielding the same image, and a real army of men as well:

Your breath first kindled the dead coal of wars

Between this chastised kingdom and myself,

And brought in matter that should feed this fire,

And now 'tis far too huge to be blown out

With that same weak wind which enkindled it.

(TLN 2337-41)

37Lewis's defiance creates an interestingly ambivalent moment for the audience; there is some satisfaction as Pandulph finds his own machiavellian arguments turned against him--even the Bastard applauds his defiance ("By all the blood that ever fury breathed, / The youth says well" [TLN 2381-2])--but at the same time Lewis has become a profound threat to the English cause, especially since the audience will be aware that the Bastard presents King John in a far more positive light than he deserves. Lewis clearly sees through the Bastard's bravado, and increasingly gains the power to overwhelm the English forces; as a result, John's capitulation to the Church is both weak and ineffective. In this instance, Pandulph's strategy is thwarted by further strategy, and any claim the Church may have to moral standards is shown to be insincere.

38There do appear to be some less morally ambiguous moments in the play when political manipulation is circumvented by actions that are driven by conscience. Hubert chooses not to blind Arthur, and Melun confesses the treachery of the French to the English lords. In each case, however, these actions, seemingly providing a moral frame of reference for the wider debate about the validity of oaths sworn to a questionable cause, are also found ultimately to be fruitless: Arthur dies anyway, and, while the English lords do indeed "Unthread the rude eye of rebellion" (TLN 2472), their actions are not shown to be the crucial event that decides the fate of the war between the French and English; the messenger that brings Lewis the news that the English lords have "fall'n off" (TLN 2537) adds in his next breath news of a further decisive disaster, that the vital "supply"(TLN 2438) Lewis needed is wrecked on Goodwin Sands in the Channel.

39In each case, happenstance rather than any moral choice is the trigger for the plot. Shakespeare underlines the effects of sheer misfortune in the similarly bad weather that the Bastard suffers, losing "half his power" (TLN 2597) in the Lincolnshire Washes (tidal flats). According to Holinshed, and in TRKJ, it is King John who loses his train--his followers and his baggage, including the crown. The overall effect of these accidents is to reduce the level of human agency in deciding the outcomes of the various debates and political manipulations we have witnessed through the play. It is something of a paradox that a play so intensely political suggests in the end that human attempts to manipulate events--however skillful--are ultimately without effect. As I have earlier suggested, in some measure King John remains firmly within the de casibus tradition where Fortune is the ultimate arbiter of human events; but the play's emphasis both on the ineffectiveness of political manipulation and of morally-driven action (notably Hubert's refusal to blind Arthur) suggests a world where human action takes place in a moral vacuum. Phyllis Rackin remarks that in this play "every source of authority fails and legitimacy is reduced to a legal fiction" (Stages 184), and Judith Weil describes King John as a "decentered and indeterminate play" (46). There is perhaps something of a foretaste of the end of King Lear, where sheer chance means that Cordelia is killed just before help arrives.

40Given that the English army is rescued by the weather rather than by its army, it is surprising that the play has so often been read as something of an exercise in patriotism. No doubt the Bastard's final rousing words have much to do with this response, and the English do, after all survive the invasion, but the method of their success may have been of little comfort to an original audience, still very much aware of the dangers of Spanish ambitions to subdue the English as enemies of the Catholic church. There have been many attempts to find specific topical references in the play, mostly in an attempt to date it in quite widely varying years (see the Textual Introduction); whatever the specific year of composition or original production of the play, the threat lingered throughout the period, as hostilities were periodically renewed; it is perhaps notable that bad weather played a major part in the English success in the Armada of 1588.

41The emphasis on chance in the resolution of King John's plot has been one of reasons why the play has been criticized as poorly constructed; the more detailed scenes at the conclusion of TRKJ rely less on coincidence, offer much more explanation, and provide a more clearly triumphant conclusion. Shakespeare's suppression of any mention of the heir apparent, Prince Henry, until just before the end of the penultimate scene is a further means by which the plot emphasizes the fragility and tenuousness of the English position. When he does appear, Prince Henry is given surprisingly passive, meditative language, in sharp contrast to the Bastard's continuing push to action. Henry speaks of himself as the "cygnet" to his father's "pale faint swan" (TLN 2627), and wishes that his tears could relieve his father's fever--to which the fretful king replies unkindly, "The salt in them is hot" (TLN 2654). On his father's death, Henry speaks piously of the omnipresence of death in the passage quoted above, "Even so must I run on, and even so stop" (TLN 2777), and his final words stress the pathos of the moment rather than the imperatives of the future:

I have a kind soul that would give thanks,

And knows not how to do it but with tears.

(TLN 2719-20)

42The dramatic focus falls again on emotion rather than on the issues that have been so extensively debated earlier in the play. Dramatically, the choice a director makes in casting Henry is important, especially in the apparent age of the actor. The Henry Shakespeare found in the chronicles was only nine years old, significantly younger than the historical Arthur, who was fourteen. Shakespeare has made his Arthur quite clearly younger than fourteen, but Henry's age is not readily determined from his characterization; some directors have cast the same actor in the parts of Arthur and Henry, a doubling that hints that the future of the kingdom is no more secure than it would have been if Arthur had succeeded to the crown. The costume designs for Herbert Beerbohm Tree's extravagant production of 1899 suggest that Arthur and Henry, played by different actors, were cast in such a way that they appeared to be about the same age.

In any case, Henry's passive language interestingly undercuts, or underplays, the importance of his legitimacy--which is certainly greater than his father's, or than the claim that Lewis made through Blanche, daughter of John's elder sister (see the family tree).

43One potential point of tension in the final scene that Shakespeare seems not to focus on is the surrender of the Bastard to the authority of the young king. Royal blood does, after all, beat in the Bastard's veins, and Shakespeare has created for him a character that is dynamic and willing to take on authority. In his meeting with Hubert in the previous scene, there is a passage that has been interpreted as signaling a crucial renunciation by the Bastard of any claim on the throne he might have:

Withhold thine indignation, mighty heaven,

And tempt us not to bear above our power!

(TLN 2695-6)

44His use of the plural in, "tempt us," however, suggests that he is not thinking of himself alone, and may be planning a more cautious strategy than has hitherto been his style (it would require an odd linguistic paradox for him to use the royal plural while forswearing ambition to royalty). Instead, the Bastard leads the way in acknowledging the new king, and continues the cheerleading now made largely unnecessary by the retreat of the French army, with his final rallying cry:

This England never did, nor never shall

Lie at the proud foot of a conqueror

But when it first did help to wound itself.

(TLN 2723-5)

45It has to be said that this is a somewhat conditional statement. England will do well when, and if, it stops internecine warfare. Both Shakespeare and his audience would have been aware of the destructive effect of continuous war, as his earlier plays on Henry VI and Richard III amply demonstrated--as also Richard II, if it was written before King John. Even the Bastard's final declaration, taken so often in earlier centuries as unabashed patriotism, ends, as does the play, with a conditional clause that contains a warning within its triumphal imagery:

Now these her princes are come home again,

Come the three corners of the world in arms

And we shall shock them: naught shall make us rue,

If England to itself, do rest but true.

(TLN 2726-9)

46Shakespeare condensed and made ambiguous the straightforward storytelling of TRKJ, and in the process created a kind of meta-debate between the worlds of the two plays. The collective effect of Shakespeare's changes to TRKJ is that he creates greater ambiguity, and gives external events greater influence on the result of the struggles between the human agents. TRKJ, like Richard II, presents debates at some length about divine right and the responsibility of the subject to leave justice to god. In contrast, the debates in King John are more worldly, as they examine ethical issues of legitimacy and the breaking of oaths, but in the end the plot shows virtuous action to be of disconcertingly little account. Shakespeare intensifies both the political scheming by almost all characters, and at the same time highlights the deeply ironic ineffectiveness of all the scheming. If the result of this pessimism is that the play leaves uncomfortable questions unanswered, it is because there is no easy resolution. In the meta-debate between TRKJ and King John, Shakespeare dismisses the cheerful conventionality of the earlier play, and creates something of a problem play (in the Ibsenian sense) with "commodity," political expedience, and self-interest the focus both of the debates between characters and the motivations that drive them.

47A "distributed" structure

We have seen that King John has scenes of great power as characters evince strong emotion, and stages debates that destabilize more conventional attitudes to power and the limited effectiveness of human agency. Nonetheless, it remains an uneven play. In genre, while it fits well enough within the general category of "history," it is rather like Falstaff's unkind description of the Hostess: "neither fish nor flesh, a man knows not where to have her" (TLN 2135). In 1819, William Oxberry concisely summarized a concern about the play's structure that has often been echoed since:

King John, though certainly not the best, is amongst the best, of Shakespeare's Tragic Dramas. . . The great defect is, that the interest does not sufficiently centre in any one individual of the play, and the death of King John, the ultimate object, is not obviously connected with the minor incidents. (William Oxberry 62)

48Whatever the precise sequence in which Shakespeare wrote King John, Richard II, and Henry IV, Part One, the structures of the three plays are strikingly different. Richard II gives the lion's share of attention, and speeches, to Richard, as befits its original title in the quarto, the "Tragedy of King Richard the Second"(102 speeches, with Bolingbrook getting 67). It is also possible to see in the play a classical structure for tragedy, with Richard suffering from hubris, and more than enough hamartia (dependence on flattery, excessive contemplation and poeticizing) to cause his fall. In contrast, Henry IV, Part One distributes stage time on a wide variety of characters, a characteristic found more frequently in the comedies. In Richard II, Richard falls while Bolingbrook rises, but Bolingbrook is given far fewer lines, so distracts less attention from Richard. In contrast, there are three major figures in Henry IV, Part One--Hal, Hotspur, and Falstaff, each of whom is given a significant presence. Hotspur's fate is tragic, and his thread in the plot closely follows the traditional tragic arc, including his (at times attractive) hubris and consequent fall; Falstaff rises, ironically achieving a kind of victory at the end of the play; Hal rises somewhat in his father's eyes, but generally remains on an even keel, moving from commentator in the early scenes to an active agent in events later in the play. His refusal to take advantage of his defeat of Hotspur at the end means that he remains something of an absent prince, and clearly has a further journey to travel. One way of interpreting the plot of Henry IV, Part One is to see in it the psychomachia of the morality plays, with Prince Hal as the Everyman figure tempted by Hotspur as "Ill-weaved Ambition" (TLN 3053) and Falstaff as Vanity (see TLN 3071).

49The overall structure of King John is more like that of Henry IV, Part One than of Richard II. It also picks up from the morality plays (no doubt via its predecessor, TRKJ) the unifying device of debate, and it follows more a "distributed" model where several characters have roles of some significance, with King John, the Bastard, and Constance having most lines. Like Henry IV also it exploits the stage-worthiness of a historically fictional character (the Bastard, Falstaff) who hogs stage time to the delight of the audience. Constance disappears half way through, leaving King John and the Bastard with similar stage presence. William Watkiss Lloyd (1856) was the first to comment on the parallel rise and fall of the remaining two characters: "when the heart and health of John decline together [the Bastard] rises at once in consistency, dignity and force" (see selection 20); later critics have also discussed what is often described as the chiastic (x-shaped) relationship between King John and the Bastard (Bonjour 270, Braunmuller 72, for example). Shakespeare uses a similar structure in Richard II, where Richard's fall and Bolingbroke's rise are explicitly figured in Richard's image:

Here, cousin,

Seize the crown. Here, Cousin.

On this side my hand, on that side thine.

Now is this golden crown like a deep well,

That owes two buckets, filling one another,

The emptier ever dancing in the air,

The other down, unseen, and full of water.

That bucket down and full of tears am I,

Drinking my griefs whilst you mount up on high.

(R2 TLN 2102-11)

50The Bastard's rise to a large extent is forced by John's increasing weakness, both physical and mental, which begins from the moment he appears to gain ascendency after the second battle. It is potentially a neat structure, but history rather gets in the way. The final scene shows John dying with a whimper far removed from Richard II's dynamic end, and a Bastard who is triumphant (thanks in significant measure to the sudden withdrawal of the Dauphin's forces), but who voluntarily cedes his ascendency to the young and previously absent Prince Henry. If the final scene dramatizes the contingency and unpredictability of human actions, it does so at the cost of some structural effectiveness. King John is fascinating in its experimentation, and frustrating in the awkwardness of its ending, where it almost seems as if it is being forced against its will to conform to its historical origins. Yet the play succeeds on stage despite its structural uncertainties; it depends more on a fascination with its portrayal of political double-dealing, and on the emotional appeal of its central scenes, driven in large measure by the strength and variety of its characters.

51Character

While King John--principally via The Troublesome Reign--inherits some of its structural characteristics from the morality plays, its characters are no more capable of being reduced to abstractions than those of plays like Henry IV, similarly indebted. Shakespeare's characterization leaves room for the actor to develop roles of richness and complexity. It is no accident that early critical approaches to King John focused on character as portrayed on stage, with particular emphasis on the parts of Constance and the Bastard (see the essay on the critical reception of King John, and the extracts from early critics of the play). Character criticism has recently been the subject of some thoughtful reappraisals. As Anthony Dawson points out in his discussion of Timon, the word refers to two separate concepts:

It's easy enough to identify Hamlet or Macbeth as characters, but figures such as Timon are harder to place. On one level, of course, Timon is a "character" in a play, an "actor's name" as the list appended at the end of the 1623 folio text has it. But if we mean a person,one who projects a feeling of depth and inscrutability . . . , does Timon fit? (197)

52Character refers both to the stage presence, one of the dramatis personae required by the dramatist, and to a critical concept that leads to discussion about the character's motivation for the actions the dramatist requires. The two functions merge, of course, since the stage presence will be brought to "life" by an actor, and in the process will acquire resonance from the actor's own training and skill. Earlier traditions of acting tended to focus on scenes and speeches in a fashion that we might think more operatic than realistic, though each age (including Shakespeare's own, if Hamlet's speech to the actors is taken as an index of the time) thought of itself as creating action that was less formal, more lifelike than earlier styles. In search of authenticity, modern actors try to find a consistent psychological thread within a character, creating a kind of adopted interiority that they can use to find the most effective inflection and emotive impact of a scene or passage. Character criticism seeks to find a similar kind of interiority by bringing textual evidence to support conclusions about the character that contribute to the overall structure, meaning, and genre of the play. We are accustomed to speaking somewhat dismissively of earlier character criticism as naïvely treating literary constructs as though they were real people, but actors continue to interpret their parts through reference to their own experiences in life, and audiences continue to react to the stage constructs with an expectation that they will be moved by responses that they can recognize as identifiably human.

53I have already pointed out that speeches given to characters within King John are more evenly divided than in the tragedies. Of necessity, the less significant roles are relatively one-dimensional, though even such small parts as the prophet Peter of Pomfret provide moments of interest. The three lords who attend King John (four are listed--Essex, Salisbury, Pembroke, and Bigot--but no more than three ever appear on stage at one time) are not clearly differentiated, though Salisbury has more of a stage presence, and has the opportunity to declaim two significant passages. He offers some rather conventional hyperbole on the discovery of Arthur's body, and speaks at length of his grief as he deserts King John to support the French. There is ample opportunity for the actor to suggest either deep emotion or hypocrisy masquerading as emotion on each occasion. A similarly one- or two-note character is Lady Faulconbridge, whose reasonable indignation at the treatment afforded her reputation by her son Robert modulates to the voice of confession as she is pressed by Philip/Richard/the Bastard for the truth of his fatherhood. King Philip of France is complex enough to be sympathetic to Constance both before and after his betrayal of her, but there are few signs of any interiority to provide motivation other than the Bastard's diagnosis: a simple pursuit of "commodity."

54One relatively minor character, Hubert, does have a surprising number of speeches (52), coming third in the play after King John (95) and the Bastard (89). That he has less impact on the play than Constance (36) or even perhaps Arthur (23) may be explained by his role. He is the loyal servant of King John, who is forced to do a deed he abhors, and ultimately gives in to his better nature in shielding Arthur. A decent man, he shares with the audience his struggle in asides:

55If I talk to him, with his innocent prate

He will awake my mercy, which lies dead.

(TLN 1598-9)

His words do take possession of my bosom.

(TLN 1605)

56And we have reason to believe him, more than any character on stage, when he swears he has had nothing to do with Arthur's death. If his part in the play attracts less attention than the number of his speeches might suggest, it is because in the pivotal scene with Arthur, and in the earlier intense interchange with King John (discussed below), he acts as the straight man, responding to the urgings of other figures rather than developing his own stage presence. Hubert is a consistent, generally sympathetic character, but he does not excite a great deal of interest.

57Camille Slights has recently agued that one of the ways of testing a character is through the sense of interiority that comes with conscience--a term contemporary with Shakespeare's theater, as our more recent vocabulary of psychology is not. In all, Shakespeare uses the word "conscience" six times in King John, and only Richard III (13), Henry V (13), Cymbeline (9), and Hamlet (8) use it more often. It is striking that two history plays, written soon before and after King John, use the term with even greater frequency. Richard III brings an almost morality-play structure to the subject of conscience, in its portrayal of a protagonist apparently devoid of any. Two Executioners, carrying out their commission to murder Richard's brother, the Duke of Clarence, debate the effect and importance of conscience:

1 EXECUTIONER

How dost thou feel thyself now?

2 EXECUTIONER

Faith, some certain dregs of conscience are yet within me.

1 EXECUTIONER

Remember our reward when the deed is done.

2 EXECUTIONER

Zounds, he dies! I had forgot the reward.

1 EXECUTIONER

Where is thy conscience now?

2 EXECUTIONER

In the Duke of Gloucester's purse.

1 EXECUTIONER

So when he opens his purse to give us our reward, thy conscience flies out.

2 EXECUTIONER

Let it go, there's few or none will entertain it.

(R3 TLN 957-64)

58As he is tested further by the First Executioner, the Second Executioner resolves not to allow conscience to influence him, in a comic anticipation of Hamlet's more famous dictum that "conscience does make cowards of us all" (Ham TLN 1737):

1 EXECUTIONER

How if [conscience] come to thee again?

2 EXECUTIONER

I'll not meddle with it, it is a dangerous thing. It makes a man a coward: a man cannot steal but it accuses him; he cannot swear but it checks him; he cannot lie with his neighbor's wife but it detects him. It is a blushing shamefaced spirit that mutinies in a man's bosom: it fills one full of obstacles. It made me once restore a purse of gold that I found. It beggars any man that keeps it: it is turned out of all towns and cities for a dangerous thing, and every man that means to live well endeavors to trust to himself, and to live without it.

(R3 TLN 965-79)

59That Shakespeare is specifically thinking of the morality plays is strongly suggested by the First Executioner's response that, like a good angel, conscience "is even now at my elbow persuading me not to kill the Duke" (R3 TLN 979-80). At the end of the play, in the extended scene where ghosts come to visit Richard and Richmond, the ghosts fulfill Queen Margaret's earlier curse that "The worm of conscience still begnaw thy soul" (R3 TLN 691)--only to have Richard echo the Executioner's (and Hamlet's) judgment: "soft, I did but dream. / O coward Conscience, how dost thou afflict me?" (R3 TLN 3641-2). Especially interesting in relation to King John are several usages in the context of rights of succession: whether King Henry's right of succession to the throne of France can be made legitimately. Henry sums up the debate in his question: "May I with right and conscience make this claim?" (H5 TLN 243). In King John it is Queen Eleanor who uses the term early in the play in a similar debate about the legitimacy of a claim to the throne, as she comments on her son's confident response to Chatillon's embassy:

KING JOHN

Our strong possession and our right for us.

QUEEN ELEANOR

[Aside to John] Your strong possession much more than your right,

Or else it must go wrong with you and me;

So much my conscience whispers in your ear,

Which none but heaven, and you, and I, shall hear.

(TLN 45-9)

60Though at this point Eleanor might seem to be standing at King John's elbow in order to function as John's conscience, it is more likely that she is prompting him for political reasons, since her later influence on him is exclusively directed towards practical ends.

61King John

With the help of his mother's prompting, King John begins the play as a forceful and decisive leader when he responds crisply to the messenger from King Philip of France, Chatillon:

Here have we war for war and blood for blood,

Controlment for controlment. So answer France.

(TLN 24-5)

62And he arrives in France with an army of "fiery voluntaries" (TLN 361) hot on Chatillon's heels. But after the first indecisive battle before Angiers he becomes a follower rather than a leader, quick to follow the Bastard's ingenious but reckless advice to join forces against the town, then to follow the no less ingenious solution provided by the Citizen of Angiers--forging an alliance with France through marriage--by cheerfully bargaining away most of the provinces he came to France to protect. In this decision he is also following the advice of his mother, the formidable Queen Eleanor. He becomes fiercely independent again, as he defies the legate of the Pope, and challenges the French in the second, successful battle.

63At this point, rather like Richard III before him, he finds that success leads to a deep sense of insecurity. His actions from this point on seem to be neither leading nor following. They become those of a temporizing politician, trying one stratagem after another as they cumulatively fail: he suborns Hubert to murder Arthur (though this order becomes one limited to blinding the child); he has himself re-crowned, for reasons Shakespeare leaves unexplained; he attempts to pacify his nobles, both before and after he learns from Hubert that Arthur (supposedly) still lives; he abruptly gives up his opposition to the Pope, yielding his crown to Pandulph in a desperate attempt to retain his kingdom; threatened by the assault led by French forces led by Lewis, he hands the "ordering" (TLN 2246) of the kingdom to the Bastard as he dwindles into illness and death.

64King John's tendency to vacillate, together with an ending that provides no obvious connection between his death and his earlier actions, gives less sense of him as a tragic figure than an actor (or critic) might like, for there is little in the text that is likely to inspire sympathy. He is not given the vigor of dying fighting (Richard III, Macbeth--even Richard II dies with some valor); nor is he permitted any great self-awareness or generosity of spirit at the end.

65Actors have variously responded to this challenge. Commenting on a well-received production (1953) starring Michael Hordern as King John and Richard Burton as the Bastard, Edwin Birch astutely summed up the difficulties the role presents an actor:

King John is the politician, a chameleonic apostle of expedience. He can assume the wrath of injured majesty, become the patriot king leading his nobles against an insolent enemy; he will sell his niece to the Dauphin with a good conscience in profitable compromise; he can mock the Pope, oust his prelates, pillage the churches and scorn the horrors of excommunication; just as easily he will surrender his crown to papal authority and kiss a cardinal's ring--when the end is the security of his throne.

The review also highlighted the difficulty of making the role resonate with the audience:

[King John is] unscrupulous, treacherous, bloody-handed, the evil worshipper of Power. Yet, with only slight aid from the text, Michael Hordern makes him partially sympathetic, likeable enough for us to believe in the Bastard's faithful love for him.

(Truth, November 6, 1953)

66In his spectacular production of 1899, Herbert Beerbohm Tree added stage business at a number of places to provide extra color to the character, or actively to read against the text. In King John's interchange with Arthur after his capture, Tree emphasized the character's ruthlessness as he swung a sword to snap off on-stage flowers that Arthur had just been picking (see the discussion of this production in the performance history). More radically, Tree also made King John more consistent in his rejection of Pandulph. The prompt book details the scene. At the opening, the corruption of the Church is made eminently clear:

Two knights enter . . . and [cross] to coffer below Pandulph--and empty bags of money in them. Enter John with crown in both hands and cowl on--He kneels to Pand. throwing back cowl with toss of head. He gives Pand. crown. Pand. takes him, makes sign of cross and puts crown on John's head.

Then, when Pandulph exits, John reveals, non-textually, his real response:

Pand[ulph]. [crosse]s John in front. John makes threatening gesture behind his back. Pand[ulph]. turns to bless him. John bows head meekly.

67The performances of actors like Hordern make clear, however, the possibility of creating a consistent character from the role Shakespeare created, even if it is difficult to find enough in the part to lift it to tragedy. Unlike those other kings who scheme and use violence to attain their ends--notably Richard III and Macbeth--there are few hints of the King John's interior life. He is given no soliloquy, and the closest he comes to a confessional mode is when he hears the news of Queen Eleanor's death from a messenger: "What? Mother dead?" (TLN 1846). This brief phrase offers one of the moments when an actor can elicit some sympathy, especially given the powerful part Eleanor played in the earlier political negotiations; it is nonetheless true that John's next thought is on the practical implications of her death in weakening his position yet further: "How wildly then walks my estate in France!" (TLN 1847).

68If there is a moment in the play where King John may show signs of conscience it is in the centrally brutal act when he persuades Hubert to murder Arthur. He hesitates and hints his desire in a justly celebrated exchange. He clearly finds it difficult to bring himself to announce his real intent, never quite saying what he wants, and leaving it to Hubert to join the dots.

KING JOHN

Death.

HUBERT

My lord?

KING JOHN

A grave.

HUBERT

He shall not live.

KING JOHN

Enough.

I could be merry now. Hubert, I love thee.

(TLN 1366-72)

69Three scenes later, as King John confronts the restive nobles, conscience becomes a major concern of all characters on stage. Salisbury watches the king and Hubert confer, and presciently remarks in images that combine internal battle with disease:

The color of the King doth come and go

Between his purpose and his conscience,

Like heralds 'twixt two dreadful battles set.

His passion is so ripe it needs must break.

(TLN 1795-8)

70After his nobles stalk off the stage in indignation, when the king realizes that Arthur's (supposed) death has had the effect of weakening his position, he does seem to have stirrings of conscience:

O, when the last account 'twixt heaven and earth

Is to be made, then shall this hand and seal

Witness against us to damnation.

(TLN 1941-3)

He specifically speaks of conscience twice in the scene, first cravenly accusing Hubert of tempting him--blaming his "abhorred aspect" (TLN 1949) for his lapse--then grudgingly admitting his own complicity in a passage that draws the familiar parallel between the king's physical body and the body politic:

Nay, in the body of this fleshly land,

This kingdom, this confine of blood and breath,

Hostility and civil tumult reigns

Between my conscience and my cousin's death.

(TLN 1970-4)

The parallel suggests that John's concern is political rather than moral: it is the "civil tumult" that matters.

71There is no clear moment in the king's final scene where he seems either to accept responsibility for his failures, or to express regret for his excesses. In stressing the heat of his fever, he does speak in terms that might suggest awareness of the wrongs he has committed and the punishment he dreads:

Within me is a hell, and there the poison

Is, as a fiend, confined to tyrannize

On unreprievable condemnèd blood.

(TLN 2655-7)

But the emphasis in the scene is on the pathos of his final moments rather than on any sense of self-discovery. He dies in the middle of a speech in which the Bastard summarizes what turns out to be inaccurate and dated news. King John's death is muted, as his young heir apparent and the Bastard take center stage.

72I have earlier suggested that the structure of King John is chiastic: as John falters and fades, the Bastard rises and gains in confidence. The tipping point for King John comes as Fortune's wheel turns abruptly at the moment he is at his greatest success, with his victory in battle and the capture of Arthur. His immediate response is to feel that his triumph is insecure, as he plots Arthur's death in the passage quoted above. King John fades rapidly after the scene where he is confronted by his nobles, and gives the "ordering of this present time" (TLN 2246) to the Bastard.

73The Bastard

Shakespeare took the non-historical character of the Bastard from a hint in Holinshed, which had earlier been developed into a fuller though rather humorless character in TRKJ. It is one of the many surprises in the play that Shakespeare contructs a bastard as a positive character; Michael Neill has shown how consistently the figure of the bastard was associated with disruption, deceit, and lechery in the drama of the period ("'In Everything Illegitimate'"; see also Alison Findlay). But though the Bastard's origin is quickly revealed to be the result of the persistent lechery of Richard Coeur-de-lion, the play highlights the Bastard's royal descent rather than his adulterous origins. The Bastard's role has always been seen to be eminently stage-worthy, even in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when his manners and language at times required some careful cutting. Shakespeare gives him two major soliloquies, a series of irreverent asides in the presence of kings, an active and successful part in the military actions of the play, and finally something close to the leadership of the entire kingdom--before he willingly yields to the young Prince Henry.

74So varied are the roles the Bastard plays that some critics have found him to be inconsistent as a character, shaped more to provide necessary movement in the plot than to create the sense of a coherent personality. The Bastard's journey from the opening scenes to the last speech of the play certainly involves considerable change; Michael Manheim writes of the "Four Voices of the Bastard," distinguishing four stages in the Bastard's self-fashioning and "political coming-of-age" (127). It is fair to say that if King John has any claim to unity of vision, it will have to be the Bastard who provides it, as his is the only voice (however much it changes) that is heard consistently through the play.

75The Bastard creates a fine stage presence when he first appears. He differentiates himself both from his rather stuffy and formal brother, and from the world of the court. His language is jovial and colloquial. King John immediately finds him "a good blunt man," and even a "mad-cap" (TLN 79, 92). His initial impulse is to take his chances (TLN 159), and to seek honor rather than to hold on to his inheritance. In his first soliloquy, he comments ironically on the world he imagines he will be joining, satirizing the courtly life he has heard of, but at the same time giving a clear signal that he means to join it wholeheartedly; the soliloquy is both a comment from the point of view of an outsider and an indication that he plans to become an active agent within the world he had hitherto been excluded from. He plans to change not only in dress and manners--"Exterior form, outward accoutrement"--but to transform his way of thinking and feeling, and "from the inward motion--to deliver / Sweet, sweet, sweet poison for the age's tooth" (TLN 220-3). Flattery's "sweet poison" is most clearly what he is thinking of at this point, though the trifold repetition of "sweet" is hyperbolic enough to suggest that he is deeply aware of the insincerity behind it. Most interestingly, the Bastard claims that he will nonetheless avoid deceiving others:

. . . though I will not practice to deceive,

Yet to avoid deceit I mean to learn . . .

(TLN 224-5)

76It is this last aim, to learn, that in many ways provides the key to the Bastard's importance in the overall structure of the play. If he is felt to have multiple voices, and to change as the play progresses, it is principally because he chooses to learn and consequently to fashion himself to suit the times and circumstances. Many of Shakespeare's characters remain splendidly or defiantly unchanged in their mutable worlds--Falstaff, Coriolanus, Richard III, and so on. But others consistently change by learning more about themselves and the world around them. In the tragedies, Lear changes radically from an autocratic, self-obsessed tyrant to a self-aware man, one who has painfully learned the need for humility as he kneels to his daughter to ask forgiveness; Hamlet, surely even more multifaceted than the Bastard, mutates several times in the play as he takes on roles from grieving son to tormentor of Polonius, Ophelia, and his mother, to unrepentant murderer, to (offstage) pirate-challenger, and finally to one who has learned resignation and the need to let events resolve the issues he faces. Some of the tragic impact of both Lear and Hamlet comes from our awareness that the learning curve of their protagonists comes too late.