Stage and Screen

20"A hidden play": 1945-2003

Olivier's film marks a turning point in the history of productions of Henry V. Though as I have argued it was not as simplistically patriotic as its dedication would suggest, the film was seen for the next several decades as the apogee of the tradition of the unproblematic representation of Henry and the war exemplified by Benson and Waller. By the time of the Old Vic's post-war reopening in 1950 with Glen Byam Shaw's production, the traditional portrayal seemed to Milton Shulman to be intolerably reactionary, Alec Clunes's Henry coming across as "a blend of St. George, Lancelot, the Lord Chamberlain and the boy scout who has done the most good deeds of the week" (Evening Standard, 2 February 1951). For Shulman, Shaw's production missed Shakespeare's intention, that Henry should be a Machiavel in the mold of Edmund and Iago. The production's choices are notable for nothing so much as being out of fashion. Bardolph's execution and the killing of the prisoners were cut; Henry's army were blithe heroes who enjoyed the war -- Fluellen even chuckled at "the perdition of the athversary hath been very great" -- while the French were not so much decadent as villainous, epitomized by the dauphin's drunken near-rape of a camp follower.

21A 1951 Stratford production, directed by Anthony Quayle and starring a twenty-five-year old Richard Burton was more representative than Shaw's of the future direction of Henry V production, not only because of its more ambiguous, reflective treatment of war, but by appearing as part of the first RSC production of the full cycle of Shakespeare's history plays in sequence, a more and more common phenomenonafter the critical work of Tillyard and Campbell made it standard to conceive of Shakespeare's history plays as a single long play. The earlier plays had been adjusted toward an emphasis on the glory of Henry's reign, with Falstaff -- played by Quayle himself -- as unsympathetic and unpleasant so as not to distract audience sympathies from the king. Burton, however, met with mixed reviews as King Henry, provoking complaints about his diminutive stature and a quiet voice that seemed ill-suited to bombast and declamation. But Ruth Ellis defended the casting; Burton's Henry, she argued, was suited to an audience of World War II veterans and an atmosphere in which aggressive war for profit now seemed criminal. Ellis noted approvingly that Burton's Henry was "less a vexatiously pious warmonger, more a prisoner of circumstance" (Stratford-upon-Avon Herald, 3 August 1951), and Ivor Brown agreed, arguing that the interpretation brought out the sincere, thoughtful Henry that Shakespeare intended, almost a rough draft of Hamlet (Observer, 5 August 1951). Burton's interpretation was appropriate to the time, Brown asserted, rather than a ham-handed and unnecessary "Lewis Waller of the 1950s."

22Quayle's production was revived by Michael Benthall at the Old Vic in 1955, with Burton's performance receiving better reviews as "an immensely matured study . . . without losing the mystic sense of dedication" (Audrey Williamson, qtd. in Leiter). But when Benthall toured the production in the U.S. in 1958 with Laurence Henry replacing Burton, it had lost its ambiguity, and "American critics saw only a spectacular pageant of a storybook king" (Leiter 214). The late 1950s and early 1960s, however, would see a few more experimental productions on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1956, Ontario's Stratford Festival saw a hugely influential production by Michael Langham that found a very Canadian way to connect the immediate political concerns of a Canadian audience to a 400-year old war between England and France: he cast francophone Canadian actors (including the future Stratford Festival artistic director Jean Gascon) in the French roles, and anglophones (including a young William Shatner as Gloucester) as the English. It was a star-making production for its lead, Christopher Plummer, who was praised both for his "boyish modesty" (Brooks Atkinson, qtd. in Leiter) and his ability to shift between the startlingly different rhetorical poses the king must strike.

23In 1960, London saw two rather unconventional productions of the play: one directed at the Old Vic by John Neville, an actor who had played the Chorus to Richard Burton's Henry in the same theater in 1955, and a thoroughly modernized adaptation of the play directed by Julius Gellner at the Mermaid. Neville's production pushed the 1950s tendency toward minimalist staging to its limit, using a bare stage dominated by a huge "No Smoking" sign. While this seemed promisingly imaginative to some critics -- W. A. Darlington praised the design's sparseness and lack of "romantic flim-flam" (Daily Telegraph, 1 June 1960) -- the production itself, what Robert Muller dismissively called "a typical actor's production" (Daily Mail, 1 June 1960), was not well received. The choice to dress John Stride's Chorus in a modern raincoat may have been the first instance of a modern-dress Chorus in the twentieth century, but Muller found it absurd, and complained that the acting quality was sacrificed for experimentation -- the "Once more" speech merely "spluttered" by Donald Houston's Henry. Reviewers in the Guardian and Times faulted the production for attempting an inappropriately realistic style of verse speaking that sacrificed audibility for pace. The entire cast shouted breathlessly, with the exception of a nineteen-year-old Judi Dench, who was universally praised for her smoothness and whom Darlington, one of the few critics to enjoy the production, called "a charming little creature."

24The production at the Mermaid was more radical, pressing a comparison between the 1415 campaign and the 1944 invasion of Normandy that an anonymous Observerreviewer found effective -- it "conveys a timeless sense of war as a heroic dimension of mankind, coupled with a realistic appreciation of its horror and futility" -- if unsubtle, sacrificing every consideration to "a single aim, that of breaking from convention as sharply as possible" (25 February 1960). Other reviewers were less kind; Edward Goring compared the "pointless production" to a more than usually stupid panto. Still, the audacity could not be denied, and even purists admitted its capacity to bring Shakespeare to the Shakespeare-hating masses. William Peacock's Henry opened the play wearing cricket flannels, suggesting an upper-class British attitude to war as sport. Battle scenes featured onstage field guns, searchlights, and sandbags, behind which Peacock whispered the "Once more" speech before leading his troops, trench warfare style, over the top. Catherine's language lesson took place in a salon, with the language competing with the noise of hair dryers. Gellner made frequent use of film, projecting World War II newsreels and Brechtian captions onto the sandbags. He also adapted the text freely, updating it to match the staging with such lines as "Think, when we talk of horses, that you see tanks, / Printing their steel tracks i' the receiving earth."

25In 1964, Peter Hall directed Henry V as part of the RSC's second major production of the cycle under the title The Wars of the Roses. As this title for the larger sequence indicates, the emphasis was on the continuity between the two tetralogies, and so Henry V, a play that studiously avoids explicit mention of the civil wars that follow its triumphant subject matter, was deftly pressed into service as a prologue to the titular wars, with every aspect of the production, as Bernard Levin put it, "subordinated to the grand design" of the history cycle (Daily Mail, 4 June 1964). Thus Henry's soldiers at Agincourt wore anachronistic surcoats with Lancastrian red roses, and Hall magnified the role of Cambridge, whose treason historically prefigures the York-Lancaster wars. The other two traitors were cut, and Cambridge was established as a spy for the French by his sinister presence in the 1.2 council scene, dressed in black and speaking lines originally written for other characters. Hall even composed and inserted new lines for Cambridge at his arrest to clarify his historical role and prophecy the coming civil war (see TLN 784-86 n.). The costume design stressed the passage of time more than the play's narrow focus would seem to allow, with Ian Holm's Henry beardless and youthfully-dressed in the opening scenes, bearded and mature at the end. The casting of Holm itself subtly enforced the sense of continuity, as he played the role in repertory with his performance as Richard III in the same cycle, the charismatic hero-king prefiguring the charismatic villain. Even the climactic triumph at Agincourt was presented as a temporary measure, as the Timescritic observed, as Henry's prayers of supplication before and thanksgiving after the battle were given more weight than usual to connect them to the dynastic curse against which the king struggles: "the sense of temporary deliverance from a curse also pervades the moment of victory…. Henry and his followers assess their fortunes in dumbstruck amazement and depart almost on tip-toe as if afraid the heavens may yet turn against them" (Times, 4 December 1964).

26Holm's was an understated and sincere Henry, who argued out his speeches rather than declaiming them, and the production as a whole strove toward reflection rather than bombast. Critics were divided about Holm, some complaining that his diminutive stature and affect were "drab and uninspiring" (Leicester Mercury), that his "Once more" speech was "more of a desperate plea than a rallying cry" (Wolverhampton Express and Star), that he was inappropriately introspective, "almost a Hamlet" (Liverpool Post). But others praised his interpretation's quiet sensitivity and intelligence and found its departure from the jingoistic tradition of Lewis Waller and Olivier's film refreshing. Herbert Kretzmer saw the performance's complexity as its strength: Holm's Henry was "a man who continually invites our understanding of the complex dilemma of kingship" (Daily Express). This sense of dilemma was exactly what Hall intended. As his essay in the production's program argues, the play is full of "the ironies of political government." Henry is effective, if not always moral, "both a devious politician and a man of sincerity; a hypocrite and an idealist." Trevor Nunn would later comment that the 1964 production done "in the midst of the 'make love not war' movements and the horror of the Vietnamese situation," marked a real interpretive turning point for productions of Henry V; it recognized what Nunn called the "play-within-a-play, a hidden play which amounted to a passionate cry by the dramatist against war" (qtd. in Berry 62). By 1964, ambiguity had become the play's foremost virtue: "Henry V is a great jingoistic celebration of England as a nation," Hall writes, "and also a criticism of the needs of kingship. It is a celebration of war and a criticism of war. An ambiguous document: Shakespeare always is."

27Hall's exploration of the play's ambiguity was a turning point in twentieth-century productions of Henry V, one that proved especially marked in North America, where Vietnam loomed large. When Michael Langham produced the play again at Stratford in 1966, it was, "in contrast to his 1956 staging, decidedly more realistic than romantic" (Leiter 215), and Langham referred to Vietnam in his production's program. Michael Kahn's stridently anti-war staging at New York's American National Theatre in 1969 presented war as a game, with actors fighting on a playground before the play began, and with costumes ranging from Viking to Vietnam to futuristic, suggesting the timelessness of war. Kahn's arguments went too far, according to many critics, but Peter D. Smith identified its "great value . . . that it opened the debate in one's mind" (Smith 450).

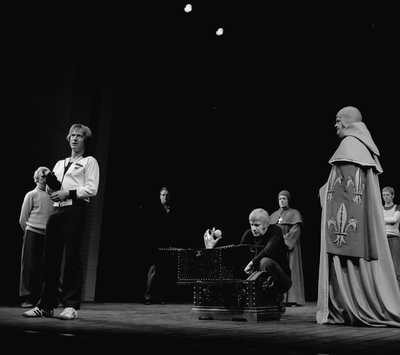

28The ambiguity in the play found expression again in Terry Hands's 1975 production for the RSC's centenary, which pushed the play's inherent links between politics and theatricality to its extremest possible expression. In the program notes, Hands argued that Hall's production, what Hands called the "Vietnam version" of the play, betrayed a misunderstanding: "I don't think the play is about war at all," he said; it is rather "about Henry V…a man who…learns to know his people." For Hands, what makes a king is his performance of kingship. Accordingly, the audience first encountered the characters as the actors playing them, warming up in rehearsal clothes before the lights went down. Emrys James's Chorus delivered the prologue simply with the house lights up, Alan Howard's Henry started the council scene in street attire, and the cast remained onstage for much of the play, cheering and jeering each other's performances. In order to highlight the progression of Henry's theatricality, as the play went on, various actors gradually, sometimes on stage, began to don costumes appropriate to their characters, but the Chorus's repeated apologies for the limitations of theatrical representation were especially effective throughout this production as a reminder that politics is theater, that our thoughts deck our kings. While some found the costuming experiment wearisome, an unsubtle joke about budgetary austerity and a plea for more Arts Council funding, it certainly made its political point; Gordon Parsons saw an indictment of Nixonian hypocrisy in Howard's "God fought for us" (Morning Star, 9 Apr. 1975). More interestingly, few critics seemed surprised by Hands's argument that Shakespeare's depiction of politics in Henry Vis subversive. Some critics continued to discuss a "usual" version of the play -- bombastic, conservative, and blatantly patriotic -- but they did so in order to dismiss such interpretations as wrong-headed. Howard, wrote the Sunday Telegraph reviewer, "was an actor playing a man playing a king: an exercise in introspection far removed from the usual recruiting poster" (Sunday Telegraph, 13 Apr. 1975). By 1975, the experimental, radical, morally ambiguous version of the play had become the new norm, the idea of a "traditional" interpretation more and more a misnomer.

29If Hall's 1964 production had been the Vietnam version of Henry V, then perhaps Adrian Noble's 1984 production at the RSC -- starring Kenneth Branagh and several other actors who would reprise their roles in Branagh's 1989 film -- could be described as the Falklands version. Though its portrayal of Henry was not entirely unsympathetic, the production emphasized more than most the difference between the ruling class's experience of war and that of the common man. When the king and nobles exited toward their ships in 2.2, for example, Henry's confidence in the divinity of his cause was reflected in the costume design: he and his men gleamed in white tabards, silvered helmets, and blinding spotlights. This was followed immediately by a somber trio of Eastcheapers wearing grubby Saint George's crosses, mourning Falstaff and somberly loading a wheelbarrow in near darkness. Noble never allowed his audience to forget the staggering human cost of war. Branagh gave sincere weight to any lines about casualties, no matter the context -- even the threats to Harfleur and the boast to the ambassador about the widows and orphans that the Dauphin's mock would produce came with an undertone of grief. The culmination of this arc was Burgundy's frequently-cut complaint about the destruction of the French garden, highlighted by a center-stage delivery by a Burgundy on crutches that built to an angry shout. The execution of Bardolph occurred onstage, during a full eighty seconds of unbearable silence broken only by the sound of rain: Branagh's Henry stared mournfully at the kneeling Bardolph, gave a silent nodded order for Exeter to garrote the thief, and waited another twenty seconds before speaking. Even after Agincourt the tone in the English camp was somber, the revelation of the victory occurring on a stage loaded with corpses of boys, Branagh's voice breaking during the quietly prayerful numbering of the dead. Fluellen's somewhat absurd speech about Henry's link to Alexander was done through tears, and its climax, "There is good men born at Monmouth," was delivered as if to convince himself, in a desperate need for Henry to be one of those good men, to justify the cost.

30Noble's production, as critic John Barber put it, struck "a welcome if anachronistic note of near pacifism" (Daily Telegraph, 29 March 1984), but it did so with subtlety, marking a "gradual progression from rhetoric to reality" (Michael Billington, Guardian, 29 March 1984). Michael Bogdanov's 1986 touring production of the history cycle, again called The Wars of the Roses, for the English Shakespeare Company (which he founded in that year with Michael Pennington, who played Henry) made a similarly subversive argument in a bolder and more strikingly irreverent way. The costume design and staging were an eclectic mix of modern and various historical periods, allowing for constant commentary on the foreign policy and xenophobic attitudes of 1980s England. Paul Brennen's Pistol, for example, was an aging hooligan in a Nazi helmet and motorcycle jacket, who led his cohort off to war carrying a banner reading "Fuck the Frogs" and chanting the football fan's standby song "'ere we go, 'ere we go, 'ere we go," jarringly juxtaposed with the patriotic hymn "Jerusalem." Class conflict was a theme throughout this production: the lords arguing for war in morning coats and cravats seemed dangerously out of touch with the realities of warfare, and during battle, the toffish Gower seemed more concerned with the insult done by the French to the king's pavilion than with their killing of the boys. After sending Pistol, Bardolph and Nym into the breach, Fluellen and his fellow officers appropriated their hiding spot to share a cocktail and a smoke. Even the "Crispinʼs day" speech was delivered calmly in an officer's barracks, conspicuously absent of common soldiers whose condition could potentially be gentled. This Henry's band of brothers was composed only of his literal blood relations and fellow peers of the realm.

31Pennington's Henry was one of the most unapologetically unsympathetic performances in the play's history, colored chiefly by quiet menace and the amoral efficiency of a cold-war diplomat. The horror of his threats to the governor of Harfleur was only increased by his calm delivery of them over a negotiating table. Henry's silence as Bardolph screamed for clemency while he was dragged offstage to be shot was rendered all the more chilling as the king shifted immediately into laughter at Montjoy's embassy. Pennington played Henry's wooing of Catherine as a tiresome bit of diplomacy to be worked through as brusquely as possible. This, and the substantial age difference between the two actors, pushed the scene in a sinister direction. Henry circled the seated princess and hovered over her, giving lines such as "I love thee cruelly" and "It shall please him, Kate" a sense of veiled threat. Pennington's "patiently, and yielding" came off as an order, and the kiss, which Catherine clearly did not return, seemed like a form of assault. The few moments of humanity that Pennington allowed to show through in Henry's more private moments ironically emphasized the sacrifice of that humanity to the office of kingship. As he sang a pious Non nobis after Agincourt, he looked longingly offstage toward the raucously celebratory lower-class football chanting in which he could no longer participate.

32Branagh's 1989 film version gave a new generation a filmic touchstone for productions of the play, considerably more conservative in style and argument than Bogdanov's production had been, but nevertheless interested in exploring the possibility of heroism in a complicated politician and warrior, while stressing the horrific and inglorious aspects of war. The iconic image from the film may be that of Henry before Harfleur, on the traditional heroic white horse, but caked in soot and bathed in the light of a burning city, striking a heroic pose when seen at a distance, but as the final close-up of the scene revealed, doing so out of desperation and with no small amount of Machiavellian theatricality. Several of the mainstream English Henry Vs in the ensuing decade followed Branagh's approach, challenging their audiences to reexamine their conception of leadership, questioning whether the idea of heroism was compatible with an anti-war outlook.

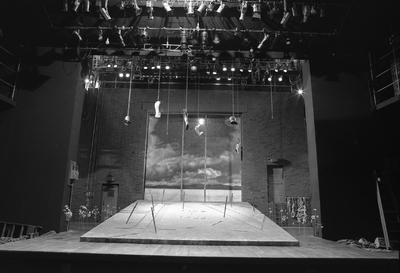

33Matthew Warchus's 1994 RSC production, for example, was an "epic of regal neurosis in the face of warfare rather than…complacent royalist propaganda" (Nicholas de Jongh, Evening Standard, 11 May 1994). Iain Glen's Henry was a dark, unknowable figure, a scheming keeper of secrets who worked not so much by winning charisma as by ruthless efficiency. Dark clouds hung over the whole production; the council scene opened with the sound of thunder as a manic Henry pored through piles of legal documents. Glen played a bookish king, proud that he had found the legal excuse to go to war through his own research, and the scene gave the impression of a back-room conspiracy to manufacture a war. Warchus emphasized the split between this private kingship and the public performance of it. Onstage audiences frequently gave rounds of applause -- at Canterbury's "such a sum," at Henry's "mock" speech -- and served both to bolster Henry's authority and to remind the viewing audience of the subject's role in constructing that authority: Glen's threats to Harfleur were underscored by his troops' rhythmic stomping, the music of his bloodthirsty rhetoric recalling a Nuremburg rally, or perhaps more charitably, a revival meeting; Benedict Nightingale called Glen's Henry "a Billy Graham of the battlefield" (Times, 11 May 1994). The production design, taking its cue from Henry's soliloquy on ceremony, emphasized the material that comprised the appearance of kingship: the idea of kingship was a main character, as the curtain call illustrated, with the actors taking their bows around a dress tree hung with Henry's costume, the finery that decks a king remaining as the last onstage image. Similarly, but more disturbingly, pieces of plate armor hung on ropes over the stage during the Agincourt sequence, reminders of the degree to which heroism comes from costume, but also grim symbols of "all those legs and arms and heads chopped off in a battle" (TLN 1983-84).

34The RSC staged Henry Vagain only three years later, with Ron Daniels directing Michael Sheen in the title role. Though Sheen received some positive responses to his portrayal of the king as a "university student suddenly whisked to royal heights" (de Jongh, Evening Standard, 12 September 1997), the production's choices -- Pistol and company as a biker gang, an eclectic mix of modern and medieval trappings, an excessively self-aware use of electronic technology -- mystified many critics. The anti-war production had become the norm, and even critics who found it too heavy-handed -- Benedict Nightingale, for instance, found Daniels to be "staging a sermon" (Times, 13 September 1997) and Alastair Macauley wrote that it was "less a play than an oratorio" (Financial Times, 15 September 1997) -- did not claim that he was misinterpreting Shakespeare's play. The production elements that most alienated critics subtly emphasized how out of their depth all the participants in the war were. The French in their shining medieval armor seemed lulled by the timeless romance of warfare, blissfully unaware of the horrors about to be visited upon them by the very modern war machine of the English, signaled by the twentieth-century uniforms worn over their chainmail. Sheen's youthful Henry, similarly, started the play lulled by a more modern rhetoric of warfare; the play opened with him watching Churchill-era newsreels, which continued running silently during the council scene, the glories of past English victories literally projected on the king's body. During the course of the play, his exuberance disappeared in the face of the realities of modern warfare; Sheen delivered the ultimatum to Harfleur sitting beside a loudspeaker, technological amplification rendering the speech at once calm and terrifyingly loud, his mechanized voice seemingly alien to his exhausted, small, very human body.

35The opening of the channel tunnel, connecting England and France by rail, occasioned a deal of public controversy between "Europhiles," who saw Britain as destined to participate in continental shared government, and isolationist "eurosceptics" who opposed the UK's entrance into the EU and adoption of the euro, and saw the tunnel as an emblem of the loss of national identity. Although Warchus's production, as its program notes remarked, opened at nearly the same time as the chunnel, it was not until 1997 that a production of Henry Vwas seen to enter into this national debate. Perhaps inevitably, given the theater's status as a lodestone for tourists and an icon of archaeological anglophilia, the debut production at Shakespeare's Globe became a focus for contemporary questions of Anglo-French relations: "Henry V," wrote critic Patrick Marmon, "was one of the original Eurosceptics" (Evening Standard, 9 June 1997). Directed by Richard Olivier, son of the most famous Henry V of all time, and starring Globe artistic director Mark Rylance as the king, the all-male Globe production determinedly struck the unfashionably patriotic notes of Shakespeare's play in the name of the same antiquarian authenticity that characterized the whole Globe project, from the reproduction of early modern tailoring practices to the hazelnut shells in the ground under the audience's feet. This production emphasized the communal experience of theater, and of English history. The role of the Chorus was shared among the company, with Rylance himself delivering the prologue before taking on the character of the king, and the program notes rather insistently encouraged audience participation. At first resistant, during the course of the run the "groundlings" entered into the spirit, whistling at the cross-dressing, enthusiastically cheering the more bombastic speeches, and booing the more-than-usually-caricatured French. Perhaps inevitably, the production came off as "lowest common demoniator slapstick," what Marmon called a "goodies and baddies crowd pleaser." The approach did not always work; Susannah Clapp found Pistol and company disappointingly flat and pantomime-like, and complained that the audience participation reduced Falstaff's death scene "to a subject for camp clucking" (Observer, 15 June 1997). Sometimes, indeed, this participation seemed not all that distant from unironically jingoistic bigotry; the audience cheering at the slaughter of the French prisoners made more than one critic uncomfortable. Given the production's overall lack of subtlety, Rylance's performance was surprisingly nuanced, "lyrical, wistful, and only reluctantly bellicose," as Clapp called it. Critics alternately praised his ability to find intimacy in a venue that called out for bombast, and decried his failure to fill the space. Rylance played against the grain, finding introspection and complexity in the midst of a larger-than-life production, as if Henry's was the only troubled mind in the playhouse, but Alastair Macauley posed the question "can introspection work at the Globe?" and found Rylance to come up wanting: "Too low in energy, he has not discovered how to make the higher flights of Shakespearian thought encompass a Globe audience" (Financial Times, 10 June 1997).

36Olivier's production opened at the Globe in the same month as another legacy Henry V director, Edward Hall (son of Peter Hall) helmed another all-male, outdoor production at the Watermill Theatre in Newbury, Berkshire. Hall was to direct the play again in a larger venue, the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, in 2000. His Henry, William Houston, played the king with an infectious energy. With an expressive face equally capable of an affable grin and a snarl, Houston was, as Nicholas de Jongh wrote approvingly, the most unpleasant Henry in memory (Financial Times, 1 September 2000), a cold bureaucrat with "a pocket calculator where his heart ought to be" (Charles Spenser, Telegraph, 4 September 2000). The production started with the entire stage draped in a huge, crude Saint George's cross flag, and continued throughout to play upon caricatures of French and English stereotypes, producing a cartoon patriotism that many critics found excessively silly: the English were football hooligans willfully mispronouncing "Har-flerr," while the French were effete aristocrats who conducted state business in a Turkish bath. Houston's Henry fairly dared his audience to like him, as if he were playing a parody of the most radical scholarly interpretations of the character. He officiously multi-tasked while delivering the traitors' sentence, and betrayed no emotion as they were executed in front of him. His order to kill the prisoners was carried out onstage over the vigorous objection of Exeter, the score dropping away to highlight the sound of the prisoners' screams as they were machine-gunned onstage. Hall's production seemed determined to undermine any notion of positive patriotism, but nevertheless critic Michael Billington found its key point to be the "English . . . truculent chauvinism that only turns into heroism in moments of crisis" (Guardian, 2 September 2000).

37If Hall's Henry V used absurdity to push the subversive elements of Shakespeare's play to their extreme, Nicholas Hytner's 2003 production at the National Theatre used insistent parallels to contemporary war toward a similar end, with grimmer, less ironic results. This was the ultimate post-9/11 production of the play, working to draw parallels, during the Anglo-American preparation for war in Iraq, between Tony Blair and George W. Bush and the play's "charismatic young leader sending his troops to war in a cause of dubious international legitimacy" (Nigel Reynolds, Daily Telegraph, 24 January 2003). An anonymous Telegraph commentator felt railroaded into this interpretation, calling it an absurd analogy that "breaks down at a hundred points" -- was Charles VI meant to be Saddam Hussein (Telegraph, 18 May 2003)? But the fact that the U.S. Defense Department suggested Henry Vas required reading for American soldiers -- a recommendation reported by the New York Timesand noted in the program -- proved that the parallel had legs. As Charles Spenser wrote, the play "might well have been written last week" (Telegraph, 15 May 2003). Hytner crowded his stage with jeeps and machine guns, and also used technology to comment on the role of television and media spin on the public reception of news. To start the second act, Penny Downie's Chorus broadcast her call to arms on the television in Mistress Quickly's pub, where the patrons flipped nervously between the war report and a snooker match. Modern war can be remembered with advantages even as it happens, and Adrian Lester played Henry as an expert in media manipulation, giving his speech before Harfleur to embedded cameramen, whom he instructed to cut the sound before threatening the city with rape and infanticide. English victories were rendered hollow by sentimentalizing video coverage, and the Non nobishymn was replaced by a jingoistic hit rap song. Lester's Henry was "chilly and severe, liable to rush in a moment from eerie restraint to cold fury" (Paul Taylor, Independent, 14 May 2003). The moments of violence on the battlefield were all driven by Henry in person, and rendered more vicious by the sudden absence of video mediation. Henry shot Bardolph and cut Le Fer's throat himself, and when his common soldiers recoiled at the order to kill their prisoners, only Fluellen, the "arch disciplinarian" (Michael Billington, Guardian, 14 May 2003), stepped forward to carry out the order. Regardless of whether they thought that the contemporary allusions worked, many critics felt that the production's agenda ironed out the play's complexities. The conservative Telegraph railed that Hytner was merely parroting the politics of previous productions and of current opinion, that "far from being daring…[he was] swimming with the tide" (Telegraph, 18 May 2003). And Michael Billington in the more liberal Guardian also wished the show had contained more of the play's contradictions. But Charles Spenser's review did identify tensions even in this most politicized of productions. The onstage killings were harrowing, he wrote:

Yet it is just as hard to forget his genuine anguish and courage on the eve of what looks like an impossible battle. Hytner and Lester have made Henry neither patriotic hero nor warmongering villain but a man caught in the moral no-man's-land of war that lies between. (Telegraph, 15 May 2003)

As we enter the play's fifth century, the most successful productions of Henry V will persist in exploring the moral no-man's-land in which Shakespeare situates this troubled hero and his war.