- Edition: Henry V

General Introduction

- Introduction

- Texts of this edition

- Contextual materials

- Facsimiles

1"Small time": the subject of the play

The fullest of the two earliest versions of Shakespeare's Henry V gives the play a title that might seem to misrepresent its subject matter. Upon opening their expensive new book in 1623, buyers of the large, folio collection of the late William Shakespeare's plays were promised The Life of Henry the Fift. As with Shakespeare's other "life" titles -- Julius Caesar, Henry VIII, King John, etc. -- what they went on to read, however, was not a full "life" in the modern biographical sense, or even the greatest-hits version of the life that we might expect in a dramatization. Those who, decades earlier, had bought the shorter, first-published version of the play, the inexpensively-printed quarto of 1600, met with a more specific title that both accurately reflects the play's subject matter and identifies the selling points of the play and its printed script: The Cronicle History of Henry the fift, With his battell fought at Agin Court in France. Togither with Auntient Pistoll. But the Quarto version's title is also misleading: the battle of Agincourt is not an addendum, but the play's main event; every scene leads up to or follows directly from the climax of England's most one-sided and famous victory.

2Shakespeare's earlier English history plays could conflate decades of history into two hours of stage time. The two-part Henry IV, for example, covers the title king's entire reign, from 1400 to 1413. The three parts of Henry VIdepict half a century of events, from 1421 to 1471, and Richard III makes the years from 1478 to 1485 seem like a few hectic weeks. Admittedly, King Henry V's reign and life were short; he died in 1422 at the age of thirty-five. "Small time," says the play's epilogue, "but in that small most greatly lived / This star of England" (TLN 3372-73). But even so, Shakespeare's Henry V takes a strikingly narrow focus both chronologically and thematically, depicting a total of some eight months in the year 1415 and a day in 1420, a small time indeed. Guided by a Chorus, an early-modern version of the device from Greek drama who serves to mediate between the audience and the events depicted in the play, we follow the build-up to King Henry's war to claim the French throne, the first wave of that war (the 1415 invasion of Picardy culminating with Agincourt), and the aftermath of the war with the 1420 Treaty of Troyes, including Henry's betrothal to the French princess Catherine. The scenes present little by way of plot, and even the war itself, depicted in acts three and four, is peculiarly fragmented and short on scenes of actual battle. The "Alarums and Excursions" that characterize other Shakespearean representations of war -- offstage noises and players as soldiers running across the stage or engaging in small skirmishes that represent the larger conflicts -- are almost absent. The only combat we see, Pistol's capturing of the French soldier Le Fer at Agincourt, immediately gives way to Le Fer's surrender and comic haggling over his ransom.

3Despite its subject matter (and despite the Quarto's title), Henry V is not a "Chronicle History" in the sense that it strictly follows the chronicle sources -- it is rather, as Alexander Leggatt puts it, an "anatomy," in whose episodic quality lies its purpose: "[w]e are not so much following an action as looking all round a subject, often in a discontinuous way. This includes not only characters and events but attitudes towards them, even ways of dramatizing them" (Leggatt 114). The play, that is, consists of a set of arguments about kingship, about politics, about power, and about English identity, all converging on the character of Henry and the multiple views of him that the play produces. Henry Vemerges as less a history of England than an exploration of the role of the individual in history. It is in this way of a piece with the other plays in Shakespeare's "second tetralogy" of English history plays: Richard II, 1 Henry IV, and 2 Henry IV. His earlier sequence of four history plays, to which Henry Vis the last of what Hollywood would call the "prequels," depicted the consequences of Henry V's early death and the unhappy reign of his son Henry VI, "Whose state so many had the managing / That they lost France and made his England bleed, / Which," as Henry V's epilogue reminds us, "oft our stage hath shown" (TLN 3378-80). The earlier tetralogy has the feel of medieval dramatic genres, the morality play and the mystery cycle. The primary agent in the plays is divine providence, and their master plot is one of human defiance of God and divine retribution, carried out through a series of curses and counter-curses that redound upon the cursers' heads. The earlier plays partake in allegory and typology, with symbolic characters such as 3 Henry VI's nameless "Father who hath killed his son" and "Son who hath killed his father" (TLN 1189-90), and miraculous events (drawn from the chronicle sources) like the ominous appearance of three suns in the sky in 3 Henry VI (TLN 677-93) or the bleeding of a long-dead corpse in Richard III (TLN 232-33). Richard of Gloucester even embodies the likable villainy of the medieval vice figure with whom he explicitly identifies (R3 TLN 1662). The more mature second tetralogy abandons this medieval framework in favor of a more human scale. Bookended by plays that depict the defining dramatic moments of their title kings' lives -- Richard II and Henry V -- the two parts of Henry IV, despite their title, are less about King Henry IV and the troubles that attended his reign than they are about the journey Prince Hal takes to the kingship, and the way he overcomes the legacy of his father's crime in deposing Richard II.

4The Chorus's declaration to the audience that "'tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings" (TLN 29) is more than a plea for imagination to patch the holes in dramatic representation. More than the life of Henry, the play is about perspectives on Henry, about the way he is clothed and constructed by the thoughts of his subjects and his audiences. It operates on a strategy of parallax: that is, a change in or distortion of perception resulting from seeing from these different perspectives; the play's different viewpoints effectively produce different Henrys. Defining the king, or rather triangulating these parallactical and often conflicting definitions of him, is the play's main business, and its major movements are structured by a logic of viewing, rather than doing.

5We can see the first movement of the play, from the Prologue to 2.1, as the mustering of perspectives. Indeed, these scenes present a barrage of them. Not a scene goes by without someone knowingly asserting some aspect of Henry's character, but in almost every case, that assertion is made in ambivalent contexts, or qualified almost as soon as it is uttered. The pattern is foreshadowed by the Chorus's portrait of "the warlike Harry," an image subtly called into question by the curious phrase "like himself" (TLN 6). What does it mean to be like oneself? Similarity is, by definition, not equality, so the apparently tautological simile emphasizes the instability of selfhood; if Henry can be like himself, then he can as easily be unlike himself, and being collapses troublingly into seeming. The bishops in 1.1 speak approvingly of the king's new character: his learning, his piety, and his diplomatic skill. But they remind us in the same breath that his reformation was miraculously sudden and that "[t]he courses of his youth promised it not" (TLN 64). Their wonder at the king's moral volte-face suggests that it is too good to be true; if indeed "miracles are ceased" (TLN 108), then there must be some more mundane explanation, and as a theologian Canterbury must recognize that the offending Adam is never truly whipped out of the mind's garden.

6The mustering of perspectives continues in the council scene of 1.2, which reinforces both of the contradictory views of Henry that the bishops offer. Henry presents very little evidence of his true character in the scene other than the apparent weighing of the "right and conscience" of his claim (TLN 243); he speaks only thirty-one of the scene's first 136 lines. But the clerics and peers fill in Henry's silence to construct him as the perfect warrior-king in the image of his ancestor Edward III. He is the heir of "these valiant dead" and their deeds, with his own "puissant arm" and "in the vary May-morn of [his] youth, / Ripe for exploits and mighty enterprises" (TLN 262-63, TLN 267-68). He is a lion of the royal blood, with the "cause, and means, and might" for the war (TLN 271-72). This English portrait of Henry is immediately contrasted with a French caricature, as the dauphin's ambassador draws an outdated picture of Henry as a man who "savor[s] too much of his youth," fitter for the dance floor and the tennis court than for the battlefield. That the English, and Shakespeare's play, embrace one of these perspectives over the other is inevitable, and the disjunction between the dauphin's view and that of the English peers fuels Henry's final, magnificent, rhetorical push into war. The parallax remains, however: both perspectives on Henry are plausible and both remain in play as the drama continues.

7The second Chorus speech reinforces the play's multiplicity of viewpoints by describing Henry with a rather ambiguous optical metaphor. On the surface, the epithet "mirror of all Christian kings" (TLN 468) seems complimentary. The primary sense is that Henry will be an exemplar for Christian kings to imitate (OEDI); indeed this sense of mirrorpredates the more common sense of "reflective surface." The play's chronicle sources repeatedly use the word in this sense to describe Henry's qualities, and Shakespeare may have derived this precise line from Edward Hall's comment about Agincourt, in which the sense of exemplaris clearly intended: "THIS battail maie be a mirror and glasse to al Christian princes to beholde and folowe" (fol. 52). But a mirror, in the more common sense (OEDII), is an imitation of reality, not the other way around; the comparison of Henry to a mirror may suggest two-dimensionality, falseness, and even, since mirror images are reversed, opposition to whatever set of values one associates with "Christian kings."

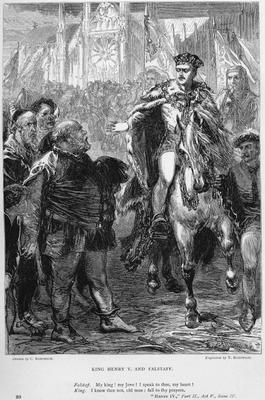

8The Chorus promises a scene set in Southampton featuring King Henry and the "youth of England . . . on fire," but that promise is immediately undercut, as the scene that follows depicts another group of characters offering a unique view of Henry, the companions of his former dissolute life. Neither young nor particularly afire with eagerness for war, Bardolph, Nym, and Pistol round out the play's first movement with another ambiguous, if not contradictory set of assertions. Bringing news of the mortal illness of Sir John Falstaff, whose company Henry abjured upon his accession in 2 Henry IV, the Hostess declares that "[t]he king hath killed his heart" (TLN 587), an assessment that meets no objection from Nym, though while he agrees that "[t]he king hath run bad humors on the knight" (TLN 619), he cannot bring himself to complain, openly at least, of Henry's rejection of Falstaff. "The king is a good king, but it must be as it may," says Nym, who then adds a comment conspicuous for its careful neutrality: Henry "passes some humors and careers" (TLN 623-24).

9The play's second movement (2.2 to 2.4) examines the immediate implications of these different perspectives on Henry, the high stakes of committing to one view of the king, and the consequences of failing to choose the right view. In 2.2 Henry teases from the traitors Cambridge, Scrope, and Grey a series of opinions about the way he, the king, is viewed: "Never was monarch better feared and loved" (TLN 654) by subjects with hearts "create of duty and of zeal" (TLN 660). The traitors' opinion is thick with dramatic irony, of course, and it is also immediately undercut: first by the revelation that at least one subject is capable of railing drunkenly against the king, and then by Henry's exposure of the traitors' plot. Seeming is not being, Henry himself points out -- the traitors, after all, seemeddutiful, grave, learned, noble, and religious (TLN 756-60) -- and the disjunction between seeming and being in these English monsters extends even to "the full-fraught man, and best" (TLN 768). The traitors' attempt to coin Henry into gold comes from their failure to view his seeming correctly, and their pleas for the mercy that he had earlier seemed to have in abundance fall upon his deaf ears. In the following scene, we hear of Falstaff's death, another fatal consequence of taking the wrong view of Henry, and in 2.4 we see such an error of perspective in action, as the Constable of France tries in vain to convince his dauphin that he is "too much mistaken in this king" (TLN 919). The constable is the only Frenchman, and perhaps the only character in the play, with a clear view of Henry's seeming and his being, an awareness that "his vanities forespent / Were but the outside of the Roman Brutus, / Covering discretion with a coat of folly" (TLN 925-27).

10The constable's moment of awareness leads into the play's third act and its third major movement, as Henry's invasion begins in earnest. The audience is imaginatively pressed into service as part of his army -- "Follow, follow! / Grapple your minds to sternage of this navy (TLN 1061-62) -- and forced into an unmediated perspective on Henry, even as his behavior becomes most difficult to interpret: is the "unto the breach" speech inspirational, or is it shocking in its reduction of men to tigers, cannons, cliffs, and so much building material with which to "close the wall up"? How are we to take Henry's brilliantly calculated good cop / bad cop routine before Harfleur, alternately threatening its most vulnerable citizens and piously solicitous for their safety? This third movement, meanwhile, extends the problem of perspective -- of judging between seeming and being -- beyond Henry: Macmorris does not know Fluellen to be as good a man as himself (TLN 1250); the French cannot justify their preconceptions of the English with their experience of fighting them (TLN 1394-1405); and Gower warns Fluellen to be on guard against the Pistols of the world, lest he be "marvelously mistook" (TLN 1527-28).

11Just before the climactic battle of Agincourt, we briefly get a fourth movement, in which Henry's own perspective on kingship threatens to emerge. "[T]he king is but a man," he opines to his soldiers, "His ceremonies laid by, in his nakedness he appears but a man" (TLN 1952-56). This sentiment, repeated in the play's only soliloquy, a disquisition on those ceremonies' feebleness and lack of substance, seems to get at the heart of the matter: Henry is aware that kingship involves skillful manipulation of the parallactical views of his subjects. This revelation of self-awareness, though, is heavily ironized by the fact that Henry is in disguise as "but a man" when he makes these observations to his soldiers, and ironized all the more by the context of the preceding Chorus speech, which describes a Henry visiting his host openly, "[t]hawing cold fear" with his "largess universal, like the sun" (TLN 1834, TLN 1832). We never see this version of Henry, but even in the Chorus's speech, his kingly qualities are compromised by the suggestion that they are mere seeming: the speech draws attention to the difference between his fearless "royal face" and his internal dread of the upcoming battle (TLN 1824-25); Henry "overbears" the "attaint" of the pallor that fear should give him, not with bravery, but "cheerful semblance" (TLN 1828-29).

12During and especially after Agincourt, the play moves into its fifth and final movement, in which the perspectives of the other characters on Henry, and the perspective of the audience, are both replaced by the inevitable perspective of history. Starting with Gower's declaration that, whatever Henry's battlefield actions, "'tis a gallant king" (TLN 2535), the end of the play hardly relents in its presentation of Henry as the epic hero of the brightest moment in England's past. Whatever his motives for the invasion of France might have seemed to be, Henry's reaction to the miraculous victory is one of modest piety. Arguably for the first time in the play, the Henry we see on stage seems consistent with the Chorus's celebratory historical view in 5.0, which rehearses the patriotic narrative of English victory for "those who have not read the story" (TLN 2851); the last perspective the play offers on Henry, that is, is the perspective of the chronicle. Likewise, the play's epilogue privileges the unified perspective of history, reminding us again that what we have been watching is not reality, but a "story" that the playwright has only roughly "pursued" (TLN 3369). But in their injunction to the audience to accept this dramatic version, the Chorus's final lines remind us of the contingency of any one perspective. The meaning of the character of Henry depends even at the last upon the audience: it is our thoughts that deck this king.