Shakespeare in Poland: The Inter-War Period (1919-1939)

Shakespeare in Poland -- page 7

6. The inter-war Period (1919-1939): scholarly and theatrical interpretations

When in 1919 Poland was at last granted independence, the country faced many political and economic problems, yet Shakespeare's plays were frequently staged in theatres. The opening of the Polski Theatre in Warsaw (1913) undoubtedly greatly contributed to Shakespeare's popularity on Polish stages. Its new technical machinery (e. g. a revolving stage) made possible the premiers of the plays (The Tempest and The Comedy of Errors) that had never been produced in Poland.

In 1924 Leon Schiller (1887-1954) began his professional career as a director. His presentations of The Winter's Tale (1924), As You Like It (1925), Julius Caesar (1928), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1934), Coriolanus (1936), and The Tempest (1947) broke away from the descriptive realism present in theatrical aesthetics and introduced the convention of the theatre of imagination, his version of "the monumental theatre." As Krystyna Duniec indicates, Schiller's interpretations of Shakespeare's plays reflect his specific approach to Shakespeare's texts. The artist was of the opinion that one should

reject everything, everything superfluous, and when necessary complete the text, translate in a form worthy of the epoch, modernise the rhyme and the action dynamics, and what is more important one should remove any traces of all kinds of historicising, archeologising [present] in the dialogue, setting, plot and costumes. (qtd. Duniec, 1998: 8)

Following his fascination with Shakespeare's plays, the director intended to create theatre that was to break the national Romantic tradition and constitute good entertainment. The archive materials show that Schiller was inspired by Vsevold Meyerhold's biomechanics, Emile Dalcroze's eurythmics, commedia dell'arte, circus and sport. His productions always evoked heated critical discussions. He was criticised for his emphasis on the openings and endings, profusion of visual and acoustic effects, diffused action, excess of group scene, and his general disrespect for Shakespeare's originals, though no one doubted that his stagings were of a great artistic value, and they for ever "intertwined Schiller's name with the name of the Bard" in the history of Polish theatre (Duniec, 1998: 184).

The period also produced many outstanding Shakespeare players. Roman Żelazowski (1854-1930) achieved especially great acclaim as Macbeth and Shylock. Józef Rybicki was one of the most lyrical Romeos and Hamlets. Kazimierz Kamieński (1865-1928) and Karol Adwentowicz (1871-1958) were praised for their modernist interpretations of Shakespeare's characters while Wojciech Brydziński (1874-1966), Kazimierz Junosza-Stępowski (1882-1943), and Aleksander Węgierko (1893-1941) experimented with psychoanalytic renderings of their roles. Stefan Jaracz (1883-1943) distinguished himself as Shylock whom he presented as "an insane miser, but not an enemy of humankind lying in ambush" (qtd. Got, 1965: 91).

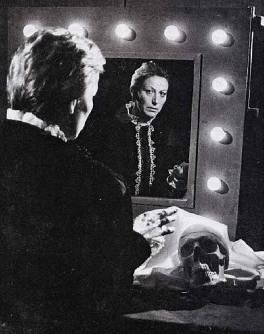

Stanisława Wysocka (1877-1941) was generally regarded as the most eminent female performer of that period. Her interpretation of Lady Macbeth--filled with inflexible austerity--was complimented by both critics and audience. She was also the first Polish female actor who played Hamlet. Like many other outstanding male players at that time, Wysocka portrayed the Danish prince as a strong person, consistent and seldom wavering in his actions (Komorowski, 2002: 190-192). Only in 1989 Teresa Budzisz-Krzyzanowska successfully ventured to follow Wysocka's example. Andrzej Wajda, the director, called this staging Hamlet IV because it was his fourth production of the play. The action was presented in two locations: in the dressing room and on the theatrical stage. Budzisz-Krzyzanowska played both Hamlet and the actor who was to play that part.

Stanislawa Wysocka as Lady Macbeth, Poznan 1929. |

Teresa Budzisz-Krzyzanowska as Hamlet, TV Theatre, 1992. |

|

Click on the images to see larger versions. |

|

Urszula Bielous noted that it was very difficult to pinpoint when the performer was becoming the character in the play. In Budzisz-Krzyzanowska's interpretation Hamlet was a reflexive and calm individual--despite all his pain and aggression--as if in her performance, the actor were writing an essay on human nature. In other words, Budzisz-Krzyzanowska was not a woman dressed up as a man, but an incarnation of Hamlet's predicament, which is not gender specific (1989: 10).

It was also the time of Shakespeare's full-fledged entrance into the Polish critical and scholarly studies. One of the most eminent monographs written at that period was Leon Pininski's Shakespeare, wrazenia, I szkice z tworczosci poety (Shakespeare, Impressions Sketches on the Poet's Works). This two-volume work gave thorough summaries of Shakespeare's plots, their sources, and an interpretation of the characters (1924). In 1914 Professor Wladyslaw Tarnawski published his monograph O polskich przekładach dramatów Szekspira (On the Polish translations of Shakespeare's plays), the work that is still regarded as a classic. In 1927 Professor Roman Dyboski wrote William Shakespeare, one of the first comprehensive studies on Shakespeare's life and work. His monograph revealed not only an extensive command of Elizabethan history, literature, and theatre but also an impressive knowledge of the European appropriation of Shakespeare, which Dyboski located in the current critical tends. There were also some attempts to trace Shakespeare's presence in Polish literature and culture. Stanisław Windakiewicz devoted his monograph to Shakespeare's influence upon Słowacki's dramatic craft (1910) while Shakespeare's tragedies served Marian Szyjkowski as a structural and thematic norm used for his evaluation of Polish playwrights (1923).

New editions of Shakespeare's plays were usually accompanied with extended introductions written by eminent Polish academics. Andrzej Tretiak wrote them for The Tempest, Hamlet, King Lear, and Othello (1923-1927). Tarnawski prefaced and edited Antony and Cleopatra, Romeo and Juliet, and Julius Caesar (1924-1926). A truly colossal enterprise was accomplished by Dyboski, who in 1911-1913 wrote a general introduction and short prologues to all Shakespeare's plays published in a twelve-volume edition of their Polish translations.

Though not of a scholarly character Tarnawski's appreciation of Shakespeare's art was probably one of the most significant studies, since it popularised the playwright among the general Polish reading public. The author's enthusiasm emanated from the pages of his little book, Szekspir: książka dla dzieci i młodzieży (Shakespeare: a Book for Children and Teenagers). Tarnawski's fascination was not surprising, since, as he confessed, he found in Shakespeare the courage to survive the continuous shelling in the World War I trenches. At that time Shakespeare helped him find the answers to the most painful existential questions, to struggle on, despite the atrocity of human fate (1931: 5).