Shakespeare in Poland: Shakespeare as Inspiration

Shakespeare in Poland -- page 13

12. Shakespeare as inspiration

Hamlet is definitely one of the most popular sources of artistic inspiration in Polish literature and art. The myth of Hamlet as the symbol of the Polish intelligentsia was ridiculed and derided for political reasons many times in post-war Polish history. Konstanty Idelfons Gałczyński wrote three of his miniatures of the Theatre "Green Goose" to disgrace this Polish Romantic myth. [Note 43] The third, Hamlet and a Waitress, was a harsh commentary on a dangerous early sixties political reality. The restless Polish intelligentsia were an object of severe persecution in the name of Stalinist law and order at the time when Gałczyński's Prince was dying of "lack of decision and twisting of the bowels at the sharp bend of history" and one of the characters was writing on his coffin "Hamlet: an idiot" (Gałczynski, 1968: 56).

In spite of this repression, a "Hamlet attitude" and hamletizing can be found not only in various dramatic texts, but also in poetry, grotesque, novels, and popular essays. As he himself admitted, Witold Gombrowicz wrote his play Wedding (1953) on the basis of Hamlet. Permeated with dramatic situations and motifs taken from Shakespeare's model, his drama becomes a philosophical meditation on the crisis of value. Sławomir Mrożek's Tango, often called "The Hamlet of The Polish People's Republic" (1964), is also full of interpretative analogies to Shakespeare's original. It is a play about dictatorship, violence, Stalinism, conformism, and a sneer at intellectualising about Hamlet.

The late twentieth century witnessed the "revenge" of Fortinbras who, ignored in the first Polish presentation of the play, came back to monopolise the entire dramatic space. The Polish interest in Fortinbras is probably conditioned by its history. Limon observes that under the Communist regime in the stagings of Shakespeare's Hamlet

the scene in which Hamlet converses with a captain of the Norwegian army that is marching against Poland (4. 4.9-20), often cut from productions elsewhere, has generally been retained in Poland, where this depiction of a foreign military threat has often been crucial for political interpretations of the play. (2001: 149)

The significance of this episodic character increased in the Polish interpretation of the play to the extent that in many theatrical renderings he was either treated as a symmetrical figure to Hamlet, or in many alternative versions of the play, he became a dominant figure in the action.

In Wariacje szekspirowskie w powojennnym dramacie europejskim (Variations on Shakespeare in Post World War II European Drama), Małgorzata Sugiera demonstrates that unlike Kott the authors of the current adaptations "do not even attempt to convince their theatregoers that Hamlet is a contemporary play." Both Jerzy Zurek in his Po Hamlecie (After Hamlet, 1981), and Janusz Głowacki in his Fortinbras sie upil (Fortinbras Has Got Drunk, 1990)

doubt the contemporary adequacy of the Elizabethan dramatist's work as a philosophical universalization of history. . . . New visions of the world, new existential experiences require a new dramatic form. (Sugiera, 1997, 42-43)

Jerzy Żurek's presents Fortinbras, initially an idealist, slowly becoming influenced by Lizon, a sober realist and political pragmatist. The ending of the play, which reflects the ending of Shakespeare's original makes the audience assume the role of Horatio. Only the theatregoers know what really has happened. Denmark's future under Fortinbras's rule looks grim, since he has become another ruthless representative of the Great Mechanism of Power. The action of the play, located in Norway, runs simultaneously with the action of Shakespeare's Hamlet. It begins with the news that a specially trained secret agent has been sent to Denmark to "enact" the role of Hamlet's father, and it ends with Fortinbras's peaceful exposition over the dead bodies of Claudius, Gertrude, Laertes, and Hamlet. The mechanisms of politics become seemingly absurd in this play, though in reality the absurdity becomes a horrifying commentary on the immortality of brutal political life and institutions.

Fortinbras's character has also inspired Polish poets. In her essay "Life After Life--Hamlet Behind the Iron Curtain," Marta Wiszniowska presents her detailed analysis of "Elegy for Fortinbras" written by Zygmunt Herbert, one of the most significant Polish twentieth century poets. Written in elegant blank verse, the poem presents Fortinbras's soliloquy over Hamlet's dead body:

Though the future belongs to the living, Fortinbras accuses Hamlet of having chosen an easy way out, subsequently making unfair claims to glory and fame. . . . The speaker is sorry for himself and the attributes of power have no appeal for him . . . Fortinbras will do the dirty job, meaningless for posterity, while Hamlet's fame will never fade.

The poem, as Wiszniowska comments, "bids farewell to the heroic, romantic Hamlet, so prominent to the Polish tradition of reading the play's message." In Herbert's poem "Hamlet is a star" still "shining," but "distant, cold, and unattainable." [Note 44]

|

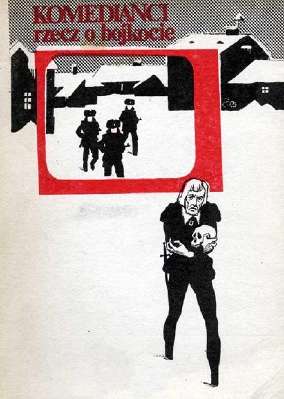

The imposition of martial law in 1981 evoked an unparalleled interest in the role of the actors in Hamlet. Since many Polish actors at that time refused to cooperate in any of the mass media, they risked poverty and political persecution. On the cover of Komedianci: Rzecz o bojkocie (Comedians: The Issue of Boycott), a compilation of stories about the Polish actors who joined the boycott, Hamlet with his skull is presented as being taken from the television studio under military guard (Roman, et al, 1990). In Janusz Kijowski's film Stan strachu (The State of Fear, 1989), the dilemma of the main character as an actor was to decide whether he was to play or not to play Hamlet in December 1981: the December of the imposition of martial law. His dilemma added a metaphorical dimension to the Polish people's situation: caught in the web of political machinations, they had then to make significant moral choices. [Note 45] |

The cover of Komedianci rzecz o bojkocie, Warsaw 1989. Click on the image to see a larger version. |

In addition to Hamlet, many other of Shakespeare's works (e.g. The Tempest, King Lear, Macbeth, and the Sonnets) have served Polish poets as an inspiration or an intertextual reference. Commenting on the long-lasting tradition, Gibinska draws attention to the latest examples present in the poetic output of Tadeusz Rozewicz, Roman Brandstaetter, Zbigniew Herbert and Wislawa Szymborska, and concludes that in the second half of the twentieth century a new quality of Shakespeare's presence in the Polish poetry emerged.

Shakespeare's texts have become an important factor in the fabric of the intellectual recognition of the difficulty of man's relation with whatever is inside or outside him. . . . Shakespeare is always the Other who cannot be appropriated into I, but may be questioned and tested, followed or negated, insulted or rewritten.

We witness at present the end of the Polish Romantic model of appropriation found in the poetic works by Mickiewicz, Slowacki, and Norwid, who "refract[ed] the Shakespearean vision into the poet's own, claiming that 'Shakespeare is me'" (Gibinska, 1999:116).

Cyprian Kamil Norwid, Shylock, drawing 1848. |

Cyprian Kamil Norwid, Hamlet, drawing 1850. |

|

Click on the images to see larger versions. |

|

With the increasing popularity of Shakespeare's works, various motifs taken from his works have appeared in Polish pictorial arts. Hamlet has most frequently served as an inspiration for Polish painters, who over centuries demonstrated their interpretation of this play in their works (cf. Cyprian Kamil Norwid, Władysław Czachurski, or Wlastimil Hofman). [Note 46] The first great painters who took up the Shakespearean themes in their works were Aleksander Gierymski (1850-1901) Władyslaw Czachorski (1850-1911), and Maurycy Gottlieb (1856-1879). Their fascination with Shakespeare started in Munich where, as students in the Academy of Fine Arts, they were encouraged to paint "A Scene from The Merchant of Venice."

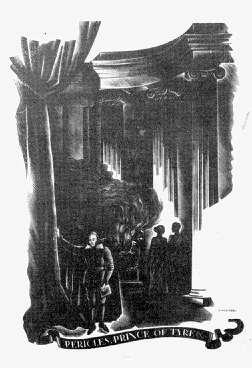

Michał Andriotti (1836-1893), an outstanding Polish draftsman and illustrator of many publications, deserves special attention here, since his art was also appreciated abroad. In 1886 he was commissioned to prepare the pictures for the edition of Romeo and Juliet by the French publishing house Firmin-Didot. A similar distinction was given to Stanisław Ostoja-Crustowski (1900-1947), an eminent graphic artist. In 1935 he won the international competition to illustrate Pericles for an edition of the play by the Limited Editions Club in New York. The value of Polish painting renditions of Shakespeare's scene does not diminish with time. In 1999 Henryk Siemiradzki's picture Antony and Cleopatra was sold at an auction in Warsaw for 260,000 zlotys (roughly 65,000 US dollars).

Elwiro Andriollo, illustration from Romeo et Juliette, Paris 1886. |

Stanislaw Ostoja-Chrostowski, illustration from Pericles, woodcut, 1940. |

|

Click on the images to see larger versions. |

|

The majority of the editions of Shakespeare's plays have also been illustrated by distinguished artists. The most famous is probably Henry Courtney Selous (1811-1890), whose woodcuts decorated the first full edition of all Shakespeare's works in Polish translation (1875-1877). [Note 47].

[Go to the page with samples of these illustrations.]

The beauty of his pictures has stirred the imagination of many Polish artists for ages. Stanislaw Witkacy was also deeply influenced by Selous's art. Some critics say that the majority of Witkacy's characters (madmen, suiciders, tyrants, ghosts, spirits, dwarfs, elfs) are, in fact, an intertextual reflection of Selous's pictures (Gerould, 1979: 533). Some actors and actresses have inspired artistic interest on the part of painters. Among them two pastels by Wyspiański belong to the Polish and international masterpieces in pictorial arts. They are the portraits of Helena Leszczyńska as Katherine in The Taming of the Shrew (1894), and Ludwik Solski as Sir Andrew Augecheek in Twelfth Night (1904).

In 2000, the Polish Association of Painters organised an open-air symposium in Kazimierz Dolny near Lublin devoted to Shakespeare's works. The artists spent two weeks in this picturesque town on the Vistula River, painting pictures on various motifs taken from his plays. The culmination of their creative meeting was a gigantic mural--a teamwork of all the participants--that shows characters from Shakespeare's dramatic and poetic works.

Notes

[43] Czesław Miłosz wrote about Gałczyński in his book Zniewolony umysł (published in English as The Captive Mind), where he presented him as "Delta." These two of Gałczyński's miniatures (respectively 1946 and 1947) can be viewed in terms of grotesque absurdity. [Back]

[44] I would like to thank here Professor Wiszniowska for sharing with me the manuscript of her work, forthcoming. [Back]

[45] The boycott of the Polish actors was actively supported by AIDA, the International Association of the Defense of Actors. Because of the efforts of its then Chair, Arianne Mnouchkine, a world famous manager and director of the "Theatre du Soleil," all French theatres donated the income from at least one of their performances to help their Polish colleagues. In the appeal for the support, the Association stressed that "for the first time in history, the artists united to boycott the governing powers in their country. Such an action was not successful in Nazi Germany, where those who refused to serve the system emigrated or lost their lives. It did not take place in Latin America, where the artists were to choose between betrayal, death, or banishment. It did not happen in France under Petain's government, nor was it successful in Spain, nor in the Soviet Union, in China, in Turkey, in Italy, or in the Czech Republic" (qtd.: Roman et al, 1990: 11-12). [Back]

[46] The information on the history of Shakespeare's presence in Polish pictorial art is taken from Ryszkiewicz and Dąbrowski (1965). [Back]

[47] Selous's pictures were reprints from Cassel's Illustrated Shakespeare, edited by Charles and Mary Cowden in 1864 (London). They were also used in the Hungarian edition of Shakespeare's plays in 1889. [Back]