Shakespeare in India (6)

Shakespeare in India -- page 6

Shakespeare on the Indian stage after Independence

Three Witches: Kannada Macbeth, directed K.V. Akshara, 1987.

Girish Karnad, the eminent contemporary Kannada playwright, remarked in an interview: 'Whenever I am asked "Who is the playwright who has influenced you the most?" I say, "Shakespeare".' [10] Karnad's play Tughlaq, featuring a medieval Delhi sultan, is steeped in Shakespeare's History Plays. Virtually all leading Indian theatrepersons since Independence have been well versed in Shakespeare. Yet it seems fair to say that Shakespeare is not a continuous or pervasive presence in post-Independence Indian drama. The end of the previous section suggests some reasons why this should be so. The Marathi B.V. Warerkar indicates the depth of the reaction to Shakespeare. 'He is not good for our modern Marathi theatre,' said Warerkar in 1964. 'Our modern age demands realism and Shakespeare cannot give us a realistic theatre. He retards it.' [11]

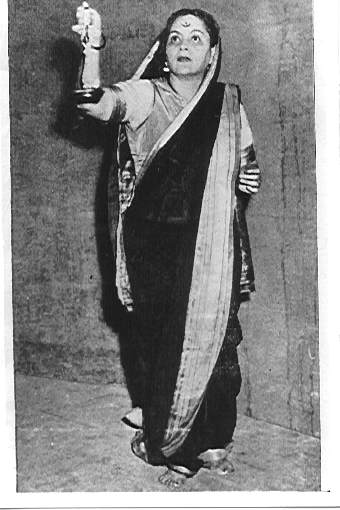

Durga Khote as Lady Macbeth in Rajmukut, a Marathi adaptation of Macbeth, 1954. |

Yet Marathi has seen the most major Shakespearean numbers since Independence: a 1950 revival of Zunzarrao (the 1890 version of Othello), V.V. Shirwadkar's adaptations of Macbeth (as Rajmukut, 'The Royal Crown', 1954, featuring the celebrated Nanasaheb Phatak and Durga Khote) and Othello (1960), Nana Joag's 3-act Hamlet (1957), Vinda Karandikar's King Lear (1974), Vijay Kenkre's Dream (1991, controversially incorporating 14 Marathi poems). One could expand the list. By contrast, the distinguished course of Bengali art theatre since the 1950s has adapted many Western plays but almost wholly eschewed Shakespeare, with the interesting exception of the Marxist actor-producer Utpal Dutt. English-language productions still have a certain presence. Amateur groups are active in most urban centres: earlier, perhaps, in Kolkata above all, but nowadays most sustainedly in the annual productions of the Shakespeare Society at St Stephen's College, Delhi. The lively English theatre in Mumbai has offered a number of Shakespeare plays over the years: among others, Alyque Padamsee's Hamlet (1964) and Othello (1990), Vikram Kapadia and Naseeruddin Shah's Julius Caesar (1992), and several plays by the Phoenix Players led by Salim Ghouse and Anita Salim. Kolkata saw a distinguished Hamlet by the Red Curtain group in 1972, and a line of productions at Jadavpur University culminating in Ananda Lal's The Merchant of Venice (1997) with its controversial female Shylock and 'Antonia'. |

Touring companies still visit regularly, chiefly from the UK under British Council auspices. But there is no sustained Shakespearean presence in the English-language theatre in India today. The situation was different 40 or 50 years ago, as evinced above all by the success of Shakespeareana. This professional company survived solely by acting Shakespeare in English, in fairly 'straight' performances across the subcontinent. In their heyday, they put on 879 performances between June 1953 and December 1956 alone. Their leader and proprietor, the expatriate Englishman Geoffrey Kendal, tells the story of the company in his lively memoirs. [12] Kendal and his family played themselves in the Ivory-Merchant film Shakespeare Wallah, based on their own lives. [External link: a group photograph of the Shakespeareana ('Shakespearewallah') troupe.]

Shakespeareana catered chiefly to school and college audiences; but it made a wider contribution by offering an early platform to Utpal Dutt, the illustrious Bengali actor, director and dramatist, and Shashi Kapoor, the eminent Mumbai film actor and scion of a celebrated cinematic family. (His father Prithviraj Kapoor had acted Shakespeare during his stint in Grant Anderson's Mumbai-based Indian National Theatre Company.)

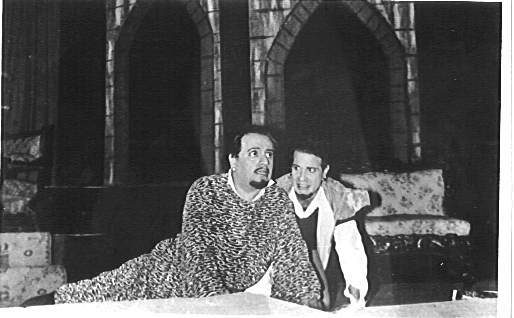

Bengali Othello, Little Theatre Group, 1958. Utpal Dutt as Othello, Shekhar Chattopadhyay as Iago.

A Marxist, Utpal Dutt also had links with the historic Indian People's Theatre Association. He wrote a scholarly if doctrinaire Bengali work on Shakespeare's social philosophy, and presented Shakespeare in the same vein through his Little Theatre Group in the 1950s and 1960s before moving on to other distinguished work. He estimates having had a hand in at least 16 Shakespeare productions. Among them are Macbeth (1954, performed at least 100 times in Bengal villages as well as Kolkata), The Merchant of Venice (1955), Julius Caesar (1957), Othello (1958), Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer-Night's Dream (both 1964). Yet the play Dutt declared himself to prefer above all was Timon, of which, in despite of his own views, he offered a surprising Christian interpretation in his book on Shakespeare.

There have been many other Bengali versions, including a spate in the Quatercentenary year, but nothing strikingly new or memorable. More creative interest has been evinced in Marathi, as described above, and in some innovative adaptations in Kannada, also cited earlier. In Malayalam, V.N. Parameswaran Pillai has offered several notable Shakespeare numbers. In Punjabi, the playwright Balwant Gargi began by following Ibsen and Strindberg. But a trip to Europe and Stratford in the 1950s converted him to the Bard, and he came back committed to a Shakespearean programme unprecedented in Punjabi drama.

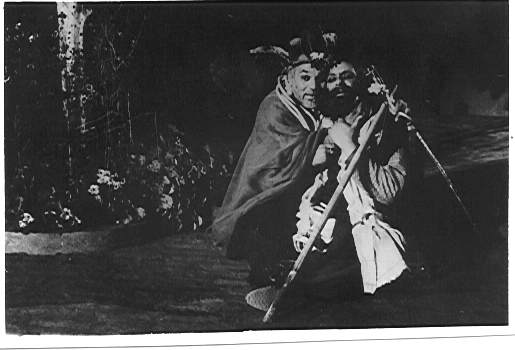

Othello and Iago: From Urdu Othello, directed by E. Alkazi, National School of Drama, Delhi, 1969.

But the most significant productions since Independence have been individual endeavours, sometimes faintly suggesting groups or trends. Delhi's National School of Drama (NSD) has a bouquet of contributions. Ebrahim Alkazi, a celebrated director of the NSD, produced a Hindi King Lear (1964) and an Urdu Othello (1969) - impressive but fairly 'straight' versions of Shakespeare's work. After professional estrangement and self-exile, he returned to produce, inter alia, a Hindi Julius Caesar (1992) for the NSD Repertory Company. The NSD also has other Shakespeare numbers to its credit, including public productions by students and even a Dream in conjunction with handicapped persons. (In a comparable social programme, inmates of a Bangalore jail acted a Kannada Julius Caesar in July 2000.)

The King and the Fool: from Maharaja Yashwant Rao, Hindi adaptation of King Lear, directed by Amal Allana. 1989

Amal Allana directed a noted Hindi Lear in Delhi in 1989. The Kolkata group Padatik produced a Hindi Raja Lear in 1988 under a German director, Fritz Bennewitz of the Weimar National Theatre. In Hindi again was Barnam Vana (Birnam Wood), a 1979 Hindi adaptation of Macbeth by a later head of the NSD, B.V. Karanth. Karanth hails from the southern state of Karnataka, and his Delhi production utilized that state's folk form of Yakshagana.

The three Witches from Barnam Vana, the 1979 Hindi version of Macbeth directed by B.V.Karanth.

Shakespeare has made more extensive entry into another south Indian dance-drama form, Kathakali. Its Delhi-based exponent Sadanam Balakrishnan produced a Kathakali Othello (1997). More curiously, the London Globe staged a Kathakali King Lear in 1999 in collaboration with Annette Leday's French Kathakali company. Also of British provenance was Hilary Westlake's adapted Shrew (1991), which used Kathakali alongside another classical Indian dance form, Bharatanatyam. Leday in her turn joined forces with the German Bremer Shakespeare Company in a Tempest (2000) where German actors represented the white colonizers in a magical island inhabited by spirits, enacted by Leday's Indian dancers.

Arjun Raina, an indefatigable Shakespearean innovator, adapted Kathakali in a 'fusion piece' combining Othello and the Dream (Delhi, 2001). Before that Royston Abel had worked Kathakali with much else into Othello - A Study in Black and White (Delhi, 1999). The play shows an Indian troupe rehearsing Othello under an Italian director and, in the process, opening up various ruptures and conflicts in contemporary Indian society. This was a trilingual production in English, Hindi and Assamese (the language of the actor playing Othello). Abel followed it up with other 'Shakespearean rehearsal' plays.

More seriously innovative was Habib Tanvir's adaptation of A Midsummer Night's Dream as Kamdeo ka Apna, Vasant Ritu ka Sapna ('The Love-God's Own, a Springtime Dream', 1993). This too is a multilingual and cross-cultural piece, planned for British players in the royal and urban roles alongside the 'mechanicals' played by rustic members of Tanvir's Naya (New) Theatre, from the central Indian tribal region (now state) of Chhattisgarh. The play incorporates the north Indian musical folk-theatre form of Nautanki. When funds dried up, the British actors were replaced by Indians from Delhi; but the play revolves round the tribal workmen, and presents a notable critique of elite culture - extending by implication to the Shakespearean original.

In 1997 came Macbeth: Stage of Blood directed by Lokendra Arambam, the radical director from the north-eastern state of Manipur. The production reflected the political turmoils of the state as well as its regional culture and ethnic practices. It was set on water: the Loktak Lake in Manipur, and later the Thames at London. Water and earth acquire traditional symbolic tones here. Birnam Wood is simulated by reed mats on boats, and Macbeth's body finally drifts out across the water - as new land emerges and the cycle of violence seems set to resume.

Tanvir's and Arambam's work provide the finest recent instances of creative Indian reworking of Shakespeare. While such productions continue, Shakespeare will retain a living presence in Indian theatre. But unlike a hundred years ago, he will not be a continuing presence in his own right, merely an occasional contributor to a theatrical agenda shaped by other themes, techniques and concerns.

Again, much of the Indian urban elite has exchanged its precious bilingualism for sole reliance on a distinctively Indian English; but this is more geared to global commerce and showbiz. At the same time, the serious Indian-language cultural enthusiast has moved on to other Western interests and grafted them more intricately into the growth of his own soil. Shakespeare struck seed in that soil two centuries ago, and will not be dislodged; but he is likely to flower less abundantly in the century ahead of us.

previous page | table of contents | next page

Notes

[10] A Tribute to Shakespeare (Theatre and Television Associates, Delhi, 1989), p.8. [Back]

[12] Geoffrey Kendal, The Shakespearewallah (Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1986). [Back]

Sukanta Chaudhuri is Professor of English at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India.