- Edition: King John

Performance History

- Introduction

- Texts of this edition

- Contextual materials

-

- Chronicon Anglicanum

-

- Introduction to Holinshed on King John

-

- Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland 1587

-

- Actors' Interpretations of King John

-

- King John: A Burlesque

-

- The Book of Martyrs, Selection (Old Spelling)

-

- The Book of Martyrs, Modern

-

- An Homily Against Disobedience and Willful Rebellion (1571)

-

- Kynge Johann

-

- Regnans in Excelsis: The Bull of Pope Pius V against Elizabeth

-

- Facsimiles

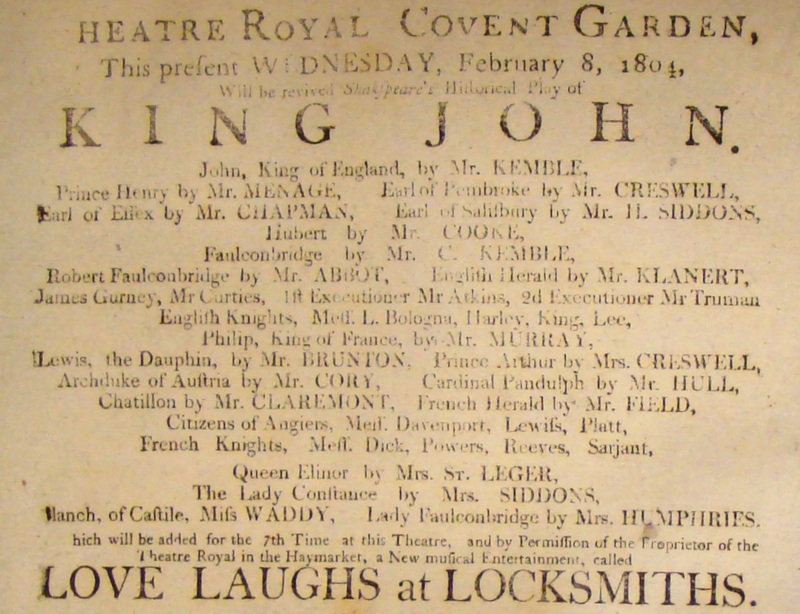

14The Restoration and early nineteenth century

King John held the stage with some regularity through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The first Restoration production had Dennis Delane in the title role at Covent Garden in 1737; it went through several performances that year (Schneider). Delane acted with his more illustrious contemporary David Garrick, and in 1745 they performed together, with Delane taking the part of the Bastard to Garrick's king (see the selection of comments by Thomas Davies from the Memoirs of the Life of David Garrick, and Pedicord). These performances provided the stage for a kind of duel between rival versions of the history, as they went head-to-head with a radical adaptation of the play by Colley Cibber, who had earlier created a stage success with his rewriting of Richard III in a form that held the stage for over a century. But when Cibber announced that he was rewriting King John, he was met with mockery (Cousin 4).

15The controversy signaled an important shift in the public perception of Shakespeare's work. Restoration audiences were accustomed to versions of Shakespeare rewritten for their tastes--Nahum Tate's King Lear is the best known, but there were many other adaptations, penned by D'Avenant, Dryden, Shadwell, Cibber and others. Cibber is most often remembered as the "hero" of later versions of Pope's Dunciad. Cibber was a staunch protestant: finding King John insufficiently anti-Catholic, he rewrote it with added anti-Catholic vituperation. In his dedication to the Earl of Chesterfield, he explains his reasons:

16In all the historical Plays of Shakespear there is scarce any Fact, that might better have employed his Genius, than the flaming Contest between his insolent Holiness and King John. This is so remarkable a Passage in our Histories, that it seems surprising our Shakespear should have taken no more Fire at it. . . . It was this Coldness then, my Lord, that first incited me to inspirit his King John with a Resentment that justly might become an English Monarch, and to paint the intoxicated Tyranny of Rome in its proper Colours. . . . I have endeavour'd to make it more like a Play than what I found it in Shakespear. . . (Sigs. A3, A4)

17His Prologue, "Spoke by the Author," damns Shakespeare's play with faint praise, as he develops an elaborate extended metaphor in justifying his revision:

18The hardy Wretch, that gives the Stage a Play,

Sails in a Cockboat, on a tumbling Sea!

Shakespear, whose Works no Play-wright could excel,

Has launch'd us Fleets of Plays, and built them well:

Strength, Beauty, Greatness were his constant Care;

And all his Tragedies were Men of War! . . .

Yet Fame, nor Favour ever deign'd to say,

King John was station'd as a first rate Play;

Though strong and sound the Hulk, yet ev'ry Part

Reach'd not the Merit of his usual Art!

19Cibber may not have won the day with his adaptation, but Shakespeare's play was not universally admired. The final comment at the end of Garrick's acting edition, derived from the prompt-book, puts Shakespeare just a short distance ahead of Papal Tyranny:

20Much the greater part of this Tragedy is unworthy its author; a rumble-jumble of martial incidents, improbably and confusedly introduced; the character of Constance intire, four scenes and several speeches of Faulconbridges, are truly Shakespearean. Colley Cibber altered this piece, but, as we think, for the worse; it is more regular, but more phlegmatic, than the original. (64)

21Perhaps because of this "phlegmatic" nature, Papal Tyranny was not a success, while King John continued to hold the stage for the remainder of the eighteenth century and much of the nineteenth. In 1745, during the controversy over Papal Tyranny, David Garrick performed John; ten years later he had decided to take on the part of the Bastard, perhaps because the character is more sympathetic, or provides more opportunity for an actor; in 1760 he played the Bastard to Richard Brinsley Sheridan's King. The Introduction to the acting edition of this production is frank about the play's apparent unevenness of invention:

22King John most certainly deserves to live on the stage, but they must be a very good set of performers who can sustain it; several scenes are highly interesting, others extremely prolix and flat. (3; sig. B2)

23Despite this distinctly qualified approval, the play held the stage for a century after Garrick. The next major production (1783), by John Philip Kemble, set the form of the play for a century; his response to the perceived prolixity of the play was to institute substantial cuts, a practice that was followed by later companies.

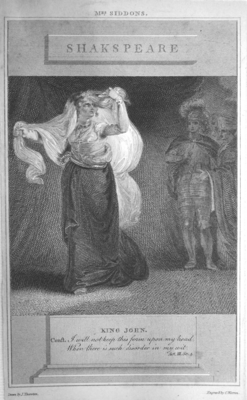

Kemble performed the play many times; William Hazlitt's review of a performance (View of the London Stage) was at best lukewarm, but he saw it after the redoubtable Mrs. Siddons had made the part of Constance her own for a generation. Mrs. Siddons played Constance in a style that evinced considerable praise:

24 [Mrs. Siddons] was ere long regarded as so consummate in the part of Constance, that it was not unusual for spectators to leave the house when her part in the tragedy of King Johnwas over, as if they could no longer enjoy Shakespeare himself when she ceased to be his interpreter. (Thomas Campbell, Life of Mrs. Siddons [London 1834], qtd. in Candido, 83)

See also the fuller discussions of Mrs. Siddons as Constance from Campbell's Life and George Fletcher on King John.

25Geraldine Cousin perceptively points out the value of King John to the star actor, given the general paucity of major female roles in Shakespeare. The general taste of the period was for a more operatic drama with fine scenes and speeches; what are today often seen as difficulties for an actor were relished in the nineteenth century.

26 From 1800, Kemble was joined by his younger brother Charles, who played the Bastard.

27The strong cast included Mrs. Siddons, still playing Constance.

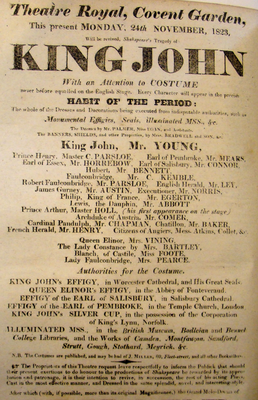

28King John as authentic history

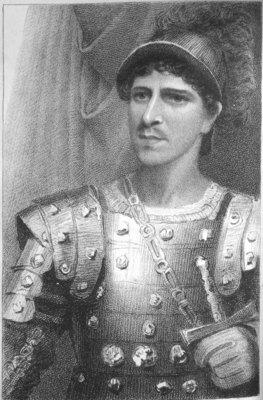

Charles Kemble continued to play the part when he teamed first with Charles Mayne Young, then with William Charles Macready. In 1823, with Young as King John, he performed Faulconbridge in a production that broke new ground in its use of stage sets and costumes.

29Charles Kemble had asked the "dramatist and antiquary" James Planché to assist him in preparing a production of the play that would have both sets and costumes authentic to the period of John's reign (Cousin 28-32). As the playbill for the production boasts, Planché spent many hours finding examples of dress from John's time; the playbill for the performance boasts that the production is presented "With an Attention to COSTUME never before equaled on the English Stage. Every character will appear in the precise HABIT OF THE PERIOD." The playbill goes on to list as Planché's sources: funeral effigies in Worcester Cathedral and various churches, an engraved silver cup, illuminated manuscripts, and recently published works on earlier habits of clothing and dress. For almost a century after this production, minutely accurate costumes and settings became the general rule for Shakespeare productions.

30 Macready's King John is exceptionally well documented. His prompt book and stage sets are preserved in the Folger Shakespeare Library, and have been published by Charles Shattuck (1962) in a collection that also includes the costume designs for the production and a carefully researched Introduction. Macready's prompt book was used by Charles Kean; Shattuck reproduces Kean's version of the play, since it "shows accurately enough the manner of Macready's staging of the play in 1842, and at the same time shows how Kean first staged it in 1846" (7). The emphasis in the production was on spectacle, not only with the elaborate and authentic costumes, but with carefully grouped staging, and choreographed movements on stage, especially in the various battles, which involved enough "extras" to make them appropriately impressive. Macready used extensive musical cues: frequent trumpets and drums especially in the battle scenes, wind instruments for martial music, and organ for the ecclesiastical moment later in the play when John yields up his crown (5.1). Macready's interpretation was noted for the strong transition he created mid-way through the play, at the point of King John's greatest triumph after winning the battle against the French and capturing Arthur. Macready signaled the change in John from victory to anxiety as he realizes he must somehow deal with the continuing threat of Arthur. Instead of a triumphant entry after the battle, the prompt book, in an entry that gives some idea of the extent of the additional characters Macready introduced in the interest of spectacle, makes clear the exhaustion of those who have won the battle, and sets the mood for the gloomy scene where John persuades Hubert to undertake the task of killing Arthur:

31[Enter] Essex, Norfolk, Fitzwalter -- and party. Enter R[ight] U[pper] C[enter] and go slowly -- as tho' fatigued -- to L[eft] D[ownstage], then Pembroke -- followed by Oxford, Arundel, and 2 English Knights, who go down, R, in same manner, -- 4 Esquires precede K John, who is speaking to the Queen Mother as they both enter -- after them Hubert, with Arthur, -- and lastly the Bastard. (Shattuck 239)

See also the reviews of Macready's performance recorded by Cowden Clark and others.

32Charles Kean, son of the more famous Edmund Kean who had played the part of King John in 1818, performed the play some years later; a review of this performance in the London Illustrated News (1852) provides some insight into the appeal both of the play and of the central character; the troubling character of King John was understood as a moral allegory, a portrait of the inevitable corruption that came with barbaric times:

33The tragedy of "King John," with its magnificent appointments, still continues to prove attractive. The character of the hero, notwithstanding his crimes, commands sympathy, for the mind habitually recognizes in him the majesty of England and of the age in which he lived, rather than the mere individual. He is a grand impersonation of the state. . . .To us this picture of regal sin and suffering has a deep meaning, and moves the reflective soul to intense emotion. . . .[More . . .]

34The illustration that accompanies the review does not show John, but the great moment of pathos in the play when little Arthur pleads with his jailer Hubert to spare his eyes:

Perhaps the character of the Prince [Arthur] was never more beautifully interpreted than my Miss Kate Terry, whose exquisite acting at Windsor Castle in the part much pleased her Majesty.

35With a splendidly Victorian moral sense, the reviewer concludes, "Such dramas are calculated to make the spectator brave and good" (London Illustrated News, April 17 1852).

See the review of Kean's performance as King John by Frederick Hawkins in his Life of Edmund Kean.

36A nineteenth-century footnote: delicacy and schoolboys

In the interests of making the reader good, if not brave, the Reverend John Valpy, Headmaster of Reading College anticipated the thorough sanitation of Shakespeare's texts by Dr. Bowdler by almost two decades. In 1803 he created an acting version of King John that smoothed many corners and made the play palatable to the parents of the boys at his school. Valpy carefully omitted references to the Bastard's origins (and in fact left out the whole first act). As he made the language more acceptable, he managed to destroy the verse:

| Shakespeare | Valpy |

| I will instruct my sorrows to be proud, | I will instruct my sorrows to be proud, |

| For grief is proud and makes his owner stoop. | For grief is proud and dignifies the mourner, |

| To me and to the state of my great grief, | To me, and to my venerable grief, |

| Let kings assemble . . . | Let kings assemble . . . |

(Quoted in Odell, 71)

37We may be grateful that this adaptation remained a footnote in the stage history of King John.

38 King John refracted through burlesque

To a modern reader, the adaptation by Valpy seems unintentionally parodic in its solemn desire to make the play respectable. It is a measure of the popularity of King John that it was given a deliberately burlesque treatment. Written by Gilbert Abbott A'Beckett, and published in 1837, King John(With the Benefit of the Act): A Burlesque provides, no doubt unwittingly, some revealing insights into audience reception of Shakespeare's original. Burlesque gains much of its humor by deflating and parodying high culture; it will seize on moments that are in one way or another memorable for the viewers who have seen the original, and who will therefore appreciate a distorted reflection of it. Through this somewhat warped mirror we can reconstruct some sense of the nineteenth century reception of King John, and even see some remnants of the nineteenth-century staging. There are fewer verbal echoes than we might expect, though there are several that quote -- and deflate -- moments of high drama. The kings greet each other before Angiers:

39 K. John. (L.C.) Peace be to France, at least, that is to say

If France, will let us have it, our own way.

Phil. (R.C.) Peace be to England, that is if t'will bow,

To our authority without a row.

(A'Beckett TLN 123-6; compare Jn 2.1 TLN 381-87)

40 In moments like these, we can imagine that the actors would not only echo the wording of Shakespeare, but exaggerate the mannerisms of actors like Macready, who had performed the part as recently as November 1836. The printed text of the burlesque includes details about the pseudo-medieval costumes the actors wore, and has as its frontispiece an illustration of the absurd costume for King John, "Breast plate, with spike in the centre, and spikes on his knees and elbows -- helmet, with a weather-cock, and N. E. S. W. on it." Richard Schoch remarks that the costume "sneeringly alludes to the vogue for historically accurate stage dress," and suggests that the weather-cock variously "expresses the provisional and mutable nature of theatrical performance," and stands for "Naughty English Wrongful Sovereign" -- though this acronym rearranges the letters as they are cited in the text of the work. More probable is the rather obvious symbolism for a king who in the public mind, in Shakespeare's original, and in the reductio ad absurdum of the burlesque, is seen to change his allegiance as the political wind -- "commodity" -- blows.

41King John's part is a starring role in the burlesque (he has six of the nine songs in the play), so it is not surprising that he has many moments that illuminate the original part. Audiences must have enjoyed his instant knighting of the Bastard:

42 K. John. I like you, sir -- your valour to requite,

I'll make of you upon the spot a Knight

(A'Beckett TLN 66-67),

43and even in the nineteenth century they may well have relished his defiance of the pope, reduced of course to a joke:

44 (Enter Cardinal Pandulph, L)

Pandulph. King John, I've got a message from the pope.

K. John. None of his usual nonsense, sir, I hope. . . .

Go tell the pope, the king does as he pleases,

And at his holy threats he only sneezes.

(A'Beckett TLN 239-44)

45More interesting is the fact that the burlesque retains the news of Eleanor's death and provides John with an exaggerated response to it, perhaps suggesting a strong stage tradition for this moment.

46Many moments in Shakespeare's original will be unfriendly to the comic world of burlesque, so it is no surprise that Arthur's scene with Hubert and his subsequent death are wholly omitted. But the burlesque provides a full treatment of the temptation of Hubert, parodying John's flattery and his habit of repeating Hubert's name:

47But Hubert, Hubert, Hubert, throw your eye

On that young lad, that now is standing by . . .

(A'Beckett TLN 301-02)

48And the moment where Hubert brings news of the mysterious appearance of five moons and reports the unhealthy speculations of the common people receive full treatment, complete with comic compound rhyme:

49 Hub. To night, my lord, they say twelve moons were seen,

Three pink, three orange, half-a-dozen green,

And in addition to this crowd of moons,

There have been five and twenty fire-balloons.

K. John. Oons! -- moons! -- balloons!

Hub. The people in the street,

Shake their heads frightfully, whene'er they meet;

And he that speaks, doth grip the hearer's button,

While what he says the other chap doth glut on.

(A'Beckett TLN 352-60)

50Some of this, no doubt, comes from a cheerful sense that the audience is superior to what will now be seen as superstitions rather than threatening portents, but it is certainly possible that many in Shakespeare's audience would have had a similar, if less patronizing reaction. The movement from the naïve stage spectacle of The Troublesome Reign to Hubert's report of the moons makes available to Shakespeare's audience an ambivalence that has become a certainty ripe for comic treatment by mid nineteenth century.

51The Bastard in Shakespeare already has some speeches where he is close to parodying the more serious-minded characters, and predictably gets some very good moments in the burlesque. His "wild counsel" is well received, and his aggressive taunting of Austria needs only a minor change in vocabulary to become unthreateningly comic:

52[Constance] That hide is quite enough to make one grin,

Thou perfect Neddy in a Lion's skin.

Aus. Oh, that a man such language would begin.

Faul. (From behind John's chair) Thou thorough Neddy in a Lion's skin.

Aus. You daren't say that again, I bet a pin.

Faul. (advancing.) You thorough Neddy in a Lion's skin.

K. John. We like not this, such fools I never saw,

You both seem Neddys by your length of jaw.

(A'Beckett TLN 230-37)

53Women on stage in the nineteenth century had become major public figures, and demanded dramatic roles to display their talents; In King John, the grief of Constance was something of a yardstick for measuring the rival talents of Mrs. Kemble, Mrs. Siddons or Helen Faucit. The burlesque includes a solo for Madam Sala, who played Constance, and she has some fine opportunities for emoting over Arthur's ill fortune, culminating in her determination to sit and demand that the kings attend her. To the Herald who has summoned her, she declaims, in phrases that clearly recall Shakespeare's originals:

54 Const. But thou shalt go without me -- do you see,

If the Kings want me, they must come to me.

. . . . .

Here I and sorrow sit, (Throwing herself on the ground) let Kings come bow,

This is my throne, I'm ready for a row.

(A'Beckett TLN 196-203)

55The earlier clash between the two women, Constance and Eleanor is reduced to a single line each, followed by a sardonic comment from Austria. Though the interchange between the women was routinely cut severely in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it is clear that enough of it survived to invite parody:

56[Philip] You do usurp the crown that should be his.

Elin. (L.) Whom do you call usurper, plain Phiz?

Const. (R.) I'll answer that your son's the man he means.

Aus. (R. corner.) There'll be a rumpus with the rival Queens.

(A'Beckett TLN 129-32)

57In at least two places, the burlesque may point to staging practices of the nineteenth century productions it is parodying. The text makes clear that, in the burlesque at least, the kings physically held hands before breaking apart under duress from Pandulph; and in the scene where John struggles to communicate his desire for Arthur's death to Hubert, he is to be imagined using non-verbal cues to support his hints:

58 Hub. Great king, you know I always lov'd you well,

Then why not in a word your wishes tell? --

Why roll your troubled eye about its socket?

(A'Beckett TLN 294-96)

59If Shakespeare's King John has a somewhat equivocal conclusion (see the General Introduction), the farce of A'Beckett's ending leaves no room for subtlety or nuance:

60 Enter all the Characters for the Finale, R[ight]. & L[eft].

Fate comes, we needs must take it, and not pick it,

Bring me the bucket, for I'm going to kick it.

Slow Music -- The King dies.

(A'Beckett TLN 466-72)

61And for the finale, to the music of La Somnambula (hot off the press from its first performance in Milan, 1831), John rises to join the performance, reassuring the audience that he'd not "the slightest idea of dying" (A'Beckett TLN 478).