- Edition: King John

Introduction

- Introduction

- Texts of this edition

- Contextual materials

-

- Chronicon Anglicanum

-

- Introduction to Holinshed on King John

-

- Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland 1587

-

- Actors' Interpretations of King John

-

- King John: A Burlesque

-

- The Book of Martyrs, Selection (Old Spelling)

-

- The Book of Martyrs, Modern

-

- An Homily Against Disobedience and Willful Rebellion (1571)

-

- Kynge Johann

-

- Regnans in Excelsis: The Bull of Pope Pius V against Elizabeth

-

- Facsimiles

10Emotion

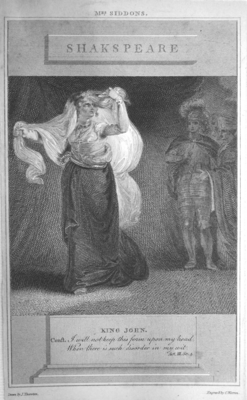

Nineteenth-century interest in the play was in significant measure driven by the way the role of Constance provided a splendid opportunity for the major actresses of the day to showcase their skills and evoke sympathy from the audience. Theater reviews discussed the relative merits of the interpretations by Mrs. Siddons, Helen Faucit, and others. A modern audience may be more impatient with Constance's outbursts, but her evocation of grief at Arthur's fate remains enormously powerful:

PANDULPH

You hold too heinous a respect of grief.

CONSTANCE

He talks to me that never had a son.

KING PHILIP

You are as fond of grief as of your child.

CONSTANCE

Grief fills the room up of my absent child:

Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me,

Puts on his pretty looks, repeats his words,

Remembers me of all his gracious parts,

Stuffs out his vacant garments with his form.

Then have I reason to be fond of grief?

(TLN 1475-83)

11The speech is sufficiently moving that earlier critics speculated that it was written by Shakespeare in response to the loss of his son, Hamnet, in 1596, though the play is generally dated somewhat earlier. In passages like this, Shakespeare comes close to the precept spoken (then immediately broken) by Berowne in Love's Labor's Lost: "Honest plain words best pierce the ear of grief" (LLL TLN 2711). More important than conjectures about Shakespeare's motivation in writing these speeches for Constance, however, is the way that they form part of a wider pattern in the play, where characters are given ample space to express strong emotion. Critics in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries tended to be rather embarrassed by the scenes of conflict between Constance and Eleanor, where the women take center stage in passionate verbal battles, perhaps because their naked emotion seemed to obscure the masculine business of political negotiation.

12Even the cameo parts of Lady Faulconbridge and Blanche stress strong emotion. Lady Faulconbridge begins in anger as she chides her son on attacking her honor, and ends in shame as she admits her adulterous relationship with Coeur-de-Lion. Blanche, whose early speeches project, on the whole, a conventionally obedient daughter, becomes for a moment the center of the rapidly centrifugal forces driving the English and French forces apart as she and Constance take center stage in a kind of competitive kneeling battle before Lewis (TLN 1232-49). Moments later, when King Philip of France releases the hand of King John and breaks off the brief alliance between the kings is broken, Blanche graphically represents and articulates the collateral damage of war:

The Sun's o'ercast with blood. Fair day adieu.

Which is the side that I must go withal?

I am with both; each army hath a hand,

And in their rage, I having hold of both,

They whirl asunder and dismember me.

(TLN 1260-4)

13The powerful emotion evoked by this visceral image of dismemberment becomes even stronger in the powerful scene where Hubert threatens to carry out King John's order to put Arthur's eyes out. In TRKJ, Arthur--who is clearly older than in Shakespeare's version--argues with Hubert on the level of ideas: that Hubert's soul will be lost by committing such a grievous sin, and that a subject is not bound to carry out a sinful order from his king. Shakespeare's Arthur plays on Hubert's feelings, emphasizing his love for his keeper: "When your head did but ache, / I knit my handkerchief about your brows." The effect is heightened by a moment of childish pride as he boasts that a princess embroidered the handkerchief--"The best I had, a princess wrought it me" (TLN 1617-19). The scene as a whole is a tour-de-force of dramatic pathos as Arthur pleads, often with precociously adult figures of speech, for his freedom from binding and blinding (see my discussion of Arthur's character, below).

14Emotion in the earlier scenes in the play is the province of the female characters, and to a large extent is generated by an articulate awareness of their own powerlessness. Arthur's predicament is a further extension of this dramatic mode after the three women have disappeared from the action. His later death offers the men in the play an opportunity to express a more masculine emotion, compassion, from positions of relative power. To my ears, however, the earls Salisbury and Pembroke indulge in self-serving hyperbole in order to justify their betrayal of the English cause:

SALISBURY

This is the very top,

The height, the crest, or crest unto the crest

Of murder's arms. This is the bloodiest shame,

The wildest savagery, the vilest stroke

That ever wall-eyed wrath, or staring rage

Presented to the tears of soft remorse.

PEMBROKE

All murders past do stand excused in this.

And this, so sole and so unmatchable,

Shall give a holiness, a purity,

To the yet unbegotten sin of times.

(TLN 2044-55)

The Bastard's less emotional, more measured and careful response

It is a damnèd, and a bloody work,

The graceless action of a heavy hand--

If that it be the work of any hand.

(TLN 2056-8)

is brushed aside as the lords prepare to meet with the forces of the Dauphin. Later in the scene, however, the Bastard reveals a deeper emotion than the lords, as he confesses that he no longer possesses his earlier confident assumption that he could understand and control the world around him:

I am amazed methinks, and lose my way

Among the thorns and dangers of this world.

15As Hubert lifts the lifeless body of the young Arthur, the Bastard meditates on the corruption of the state that has led to this moment, revealing an unexpected belief in the genuineness of the claim that Arthur had to the crown:

How easy dost thou take all England up!

From forth this morsel of dead royalty

The life, the right, and truth of all this realm

Is fled to heaven . . .

And in a graphic image he describes the savage scavenging for scraps of power unleashed by the dogs of war:

England now is left

To tug and scamble, and to part by th'teeth

The unowed interest of proud-swelling state.

Now for the bare-picked bone of majesty

Doth dogged war bristle his angry crest

And snarleth in the gentle eyes of peace.

(TLN 2145-55)

At this moment, both emotion and the analysis of power--the subject of many debates in the play--meet.

16In contrast to the Bastard's keen awareness of the moral issues he faces, King John becomes less concerned with major issues. His final moments are subdued and focus on his personal suffering. The preparation for his last entry on stage treads a fine line between pathos and comedy as Pembroke describes an ailing king, singing in his delirium. John's death is seemingly arbitrary, since Shakespeare makes no direct connection between the King's earlier order to sack the monasteries and the offstage actions of the monk who poisons him. John's final speeches make no mention of the wider debates and issues the play explores. He expresses little regret, and his lament as king is only that his political power is useless in combatting his fever:

. . . none of you will bid the winter come

To thrust his icy fingers in my maw,

Nor let my kingdom's rivers take their course

Through my burned bosom.

(TLN 2644-7)

17As in Constance's laments and Arthur's pleadings, Shakespeare concentrates on the emotional appeal of John's suffering and his sense of his own insignificance:

There is so hot a summer in my bosom

That all my bowels crumble up to dust.

I am a scribbled form drawn with a pen

Upon a parchment, and against this fire

Do I shrink up.

(TLN 2637-41)

The image of King John shrinking to a charred ember is apposite. His end gives little sense of the broader sweep of tragedy of the kind Shakespeare creates in Richard II, where Richard's death comes after an intense meditation on the nature of power, time, and pride, and he is given a moment of fierce triumph as he dies fighting. John's death is one of almost childish pathos, as he lies, aware of his own lack of power, and seemingly uncaring about the future. Nonetheless, John's death, in the hands of a good actor, can move an audience deeply; a reviewer of Beerbohm Tree's production in 1899 commented that "the stark backward loll of the corpse sent a tremour through the house." The arbitrary nature of King John's death recalls an older kind of tragedy, the simple turning of Fortune's wheel as the king becomes a "module of confounded royalty" (TLN 2668). Prince Henry picks up the image in this de casibus tradition:

Even so must I run on, and even so stop.

What surety of the world, what hope, what stay,

When this was now a king, and now is clay?

(TLN 2677-9)

18Since Henry is able only to respond "with tears" (TLN 2720), it is left to the Bastard to make a final emotional appeal to unity and patriotism. The final lines of the play, with their combination of emotion and patriotism, neatly sum up the appeal of the play to nineteenth-century directors and audiences. Eugene Waith suggests that twentieth century critical approaches have obscured the strengths that earlier productions found:

In the case of King John it may be that the tendency to look first for a pattern of ideas has kept us from understanding the power that critics once found in scene after scene. Perhaps if we are willing to alter somewhat the expectation we have cultivated, we too can feel that power (211).

19Waith's caution is salutary in reminding us of the sheer stageworthiness of many scenes in King John that dramatize the strong emotions of the characters. But it is also true substantial sections of the play, especially in the earlier scenes, are taken up with patterns of ideas: extended onstage debates on the value of legitimacy, on the uses of political power, and on the consequences of making and breaking oaths and loyalties. It is also true that the two earlier plays on King John (Bale's Kynge Johann [[ Invalid view ]] and TRKJ [[ Invalid view ]]) were explicitly plays of ideas, where the debates centered on the abuse of religion and the struggle that King John had against the church.