The prose of the Church

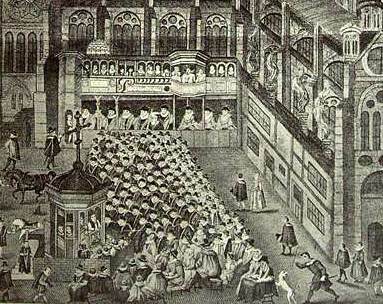

Sermons, religious meditations, the Bible, pamphlets arguing the passionate religious issues of the day: all at their best illustrate the power of Renaissance English to move the reader or listener--some of whom are pictured here listening to a preacher at Saint Paul's Cathedral.

One such preacher was John Donne in his later years. A poet and clandestine lover* in his earlier years, in 1621 (five years after Shakespeare's death) he became Dean of Saint Paul's, where his sermons were famous for their combination of deep emotion and intellectual analysis.

Read Donne's famous meditation that "no man is an island"*.

Read about another prose writer who was a major influence on T.S. Eliot.*

Donne's "Sermon Preached to the Lords upon Easter-day, at the Communion" is on line.

Footnotes

-

Donne the lover

Donne's promising career at Court was cut short by the discovery of his secret marriage to Anne More in 1601; he was actually imprisoned briefly as a result.

-

Who is an island?

Perchance he for whom this bell tolls may be so ill as that he knows not it tolls for him; and perchance I may think myself so much better than I am, as that they who are about me and see my state, may have caused it to toll for me, and I know not that. The church is catholic, universal; so are all her actions; all that she does, belongs to all. When she baptizes a child, that action concerns me, for that child is thereby connected to that Head which is my Head too, and engraffed [grafted] into that body, whereof I am a member. And when she buries a man, that action concerns me. All mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language, and every chapter must be so translated. God employs several translators; some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice; but God's hand is in every translation; and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again for that library where every book shall lie open to one another. As therefore the bell that rings to a sermon calls not upon the preacher only, but upon the congregation to come, so this bell calls us all . . .

The bell doth toll for him that thinks it doth, and though it intermit [stop] again, yet from that minute that that occasion wrought upon him, he is united to God. . . . Who bends not his ear to any bell which upon any occasion rings? But who can remove it from that bell which is passing a piece of himself out of this world? No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were Any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.From John Donne's Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions (1623). Donne was seriously ill when he wrote this piece.

-

A 17th-century T.S. Eliot?

One of the great figures of the Anglican Church in Shakespeare's time, Lancelot Andrewes was appointed Bishop of three of the great cathedrals of England: Chichester, Ely, and finally (in 1618, two years after Shakespeare's death) Winchester.

His sermons, like Donne's, combine great learning with a powerfully persuasive prose which gained much of its strength from its simplicity and directness. This passage, on the journey of the Three Wise Men before the Nativity, was used by the early twentieth century poet, T.S. Eliot as the basis for his poem "Journey of the Magi":

First, the distance of the place they came from. It was not hard by as the shepherds--but a step to Bethlehem over the fields; this was riding many a hundred miles, and cost them many a day's journey. . . . This was nothing pleasant, for through deserts, all the way waste and desolate. Nor secondly, easy either; for over the rocks and crags of both Arabias, especially Petraea, their journey lay. Yet if safe--but it was not, but exceeding dangerous, as lying through the midst of the "black tents of Kedar" (Cant 1:5), a nation of thieves and cut-throats; to pass over the hills of robbers, infamous then, and infamous to this day. No passing without great troop or convoy. Last we consider the time of their coming, the season of the year. It was no summer progress*. A cold coming they had of it at this time of the year, just the worst time of the year to take a journey, and specially a long journey in. The ways deep, the weather sharp, the days short, the sun farthest off, in solsitio brumali, "the very dead of winter."