Shakespeare in South Africa: The Earlier Twentieth Century

Shakespeare in South Africa -- page 3

The earlier twentieth century

The Leonard Rayne Era

Early twentieth century professional theatre was dominated by another Wheeler import, the producer and actor-manager Leonard Rayne (William Watts Cowie), nicknamed "The Guv'nor." Rayne, formerly a member of the stock company at Sadler's Wells, arrived with the "Holloway Theatre Company" in November 1895, and his first South African performance took place in the uneasy days leading up to the Jameson Raid. The Holloway Company (also well known in Australia) opened in the Standard Theatre with Othello on Boxing Day 1895, Rayne playing Roderigo to William J. Holloway's Othello and Amy Coleridge's Desdemona. Three days later Jameson and his party crossed the border into the Transvaal. Four months of political tension followed, but did nothing to dampen the enthusiasm aroused by the Holloway tour. Rayne played the name part in Richard II, Edmund in King Lear (performances in which rain, pelting on the corrugated iron roof and accompanied by the crashing thunder and lightening of a Highveld storm, sometimes made artificial sound effects superfluous), Polonius in Hamlet, Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing, Gratiano in The Merchant of Venice, Orsino in Twelfth Night and Sir Peter Teazle in The School for Scandal. The tour lasted 20 weeks after which Rayne returned to Sadler's Wells. But the vitality of South Africa had struck root in him, and despite tempting offers elsewhere, Rayne returned in late 1898 with his own company, which included Grant Fallowes - later to be his business manager - and the latter's wife, Annie Leaf, and they toured to Cape Town (where the gallery of the Opera House was packed with "Coloured" and Malay supporters - racial mixing not being considered appropriate even in the more relaxed atmosphere of Cape liberalism), Pietermaritzburg, Durban and Port Elizabeth, playing everything "from farce to Shakespeare" (Storrar 127). The repertory included Hamlet, alongside plays such as Virginius, A Message from Mars, Rip van Winkle, and Rayne's own adaptation of The Three Musketeers. Despite rumours of war, the tour was well-supported, though Johannesburg and Pretoria had initially to be omitted from the itinerary because of the political tensions. The company arrived in Johannesburg only in 1902, Rayne taking a two-year lease on the Gaiety Theatre.

In 1899 martial law had been declared on the Witwatersrand and most theatrical activity ground to a halt for the duration of the Anglo-Boer War. The Wheelers' theatrical entrepreneurship carried on regardless, and they were ready to open a new home for musical comedy, His Majesty's, in 1903. (The opening show was the Royal Australian Comic Opera Company's extravaganza Djin Djin.)

On the Johannesburg stage, the period between 1898 and 1912 shows five productions of Hamlet, four of Julius Caesar, one of The Merchant of Venice, one of A Midsummer Night's Dream, one of Richard III, one of The Taming of the Shrew, and two of The Tempest - and this list is by no means comprehensive (see Rosen). Shakespeare's increasing, if temporary, ubiquity was fostered by Rayne. The 1906 season at His Majesty's included Julius Caesar (10-11 September), and Hamlet (14-15 September). The Tempest followed shortly (29 December-16 January) in the William Haviland - Edyth Latimer season, which also included Hamlet (again) and The Merchant of Venice. This heightened emphasis on Shakespeare probably reflects the growing British economic ascendancy and a desire for cultural affirmation by the nouveau riche. Apart from the years of the Anglo-Boer War itself, the decades from the 1890s to the start of the First World War were a high point for Anglophone theatre in South Africa.

Though his theatrical tastes were eclectic and somewhat "soft-centred" - he was a theatrical entrepreneur par excellence - Rayne's special devotion to Shakespeare was again evident in the "Grand Shakespeare Festival" he mounted at His Majesty's in April 1907. Macbeth (with an orchestra and choir of 60), Hamlet, Othello, The Merchant of Venice, Julius Caesar and Richard III were presented in one week, with Rayne playing all the leads himself (Storrar 130).

The Post-war theatrical slump

A white-run post-war "Union of South Africa" was formed in 1910. Two years later, 1912, saw the formation of the South African Native Congress, forerunner of the ANC - an event at a considerable ideological remove from the habitus of colonial Shakespeare performance, despite the presence of the Shakespeare aficionado Sol Plaatje as its first Secretary General (see below). The arrival of the "talkies," also around 1910, temporarily throttled professional theatre, as happened all over the world. Post WW1 British policies of price "deflation" dragged the South African economy into trouble, because among the international prices soonest affected were gold and wool, the country's only major exports. Industrial turmoil followed. The English-speaking stage was particularly hard-hit, and the slump lasted through the years of the Great Depression to the end of the 30s. The theatres themselves began to disappear under the celluloid onslaught: the Opera House in Cape Town, Scott's Theatre in Pietermaritzburg, Malone's Theatre Royal in Durban, His Majesty's in Johannesburg (which had been the only theatre on the Reef to allow other races into the gallery - not, of course, into the main auditorium). Many of the buildings were converted into cinemas.

Shakespeare suffered along with the rest of the theatre, but there were bright spots. Henry Herbert and his wife Gladys Vanderzee arrived in the Cape in 1912 and gave a boost to classical theatre, playing in works such as She Stoops to Conquer, Macbeth, The Rivals, and A Midsummer Night's Dream. (Later, in 1921, Henry Herbert subjected Cape Town to a full-length Hamlet, which started at 6 pm and finished at midnight. According to Stopforth, "those who saw it vowed that it did not drag for a minute" (215).) 1913 saw two striking Shakespearean incursions. Matheson Lang (who also performed in India) paid a visit with a repertoire that included The Merchant of Venice and Antony and Cleopatra, while the Australian-born Oscar Asche, with his wife Lily Brayton, delivered a memorable performance of Antony and Cleopatra in the same year, on their way back from their successful Australian tour of 1912-13. The "four gigantic negroes" who played Egyptian slaves in Asche's cast caused an immediate strike by stage-hands (Stopforth 214): the mask of historical drama failed to salve racial prejudice.

Johannesburg marked Shakespeare's wartime Tercentenary in 1916 with a modest celebration sponsored by the Municipal Council, the Transvaal Chamber of Mines and the Witwatersrand Council of Education. Running from 23 April - 2 May, the festivities comprised a production of The Merchant of Venice at the Palladium Theatre, with music especially composed by David Foote, and a poetry competition (the winning entry by R.A. Nelson was entitled "For All Time and All People"), and they concluded with "free commemoration services" in the Town Hall, on the afternoon and evening of May 2, that pulled out all the jingoistic stops. The proceedings included renderings of "The Harp that once through Tara's Halls," "Men of Harlech," "Rule Britannia," "Ye Mariners of England"; some Shakespearean songs, "The Willow Song" and "I know a bank," "Blow, Blow, Thou Winter Wind"; the "Lullaby" chorus from Mendelssohn's music to A Midsummer Night's Dream, and "Land of Hope and Glory." Recitations included Henry V before Harfleur ("Cry, God for Harry! England! And St. George!" adorns the front cover of the souvenir programme) and selections from King John and Romeo and Juliet. The choral numbers were to be "supplied by children for children."

The winter of 1921 saw Sir Frank Benson, the grand old man of the English stage (he was 64), on tour in South Africa under the aegis of Leonard Rayne, giving Shakespeare (and himself!) a needed shot in the arm. J.C. Trewin writes that "someone was heard to say that Pa [Benson's company nickname] pictured himself toiling across the veldt in an ox-wagon, emerging now and then either for an 'eternity' Hamlet, or to defend his players from Zulu assegais" (235). The repertoire included Hamlet, The Merchant of Venice, Twelfth Night, The Taming of the Shrew, Richard III, Julius Caesar, and The Merry Wives of Windsor. These performances were so popular that the tour was extended and new works added, including (surprisingly) Othello and The Wandering Jew. With typical romantic gusto, Benson commented that the whole atmosphere in the country seemed to him reminiscent of Elizabethan times, and that those Afrikaans-speakers he met on tour often seemed more enthusiastic about Shakespeare than the English.

Sybil Thorndike's visit in 1929, which included remarkable performances of Macbeth, was memorable for the energy she committed to developing South African theatre for all races, including visits to schools. Special permission had to be obtained for the budding dramatist H.I.E. Dhlomo and a friend to attend a performance of hers in the City Hall (Couzens 60). "How could one help being influenced by its problems, its immense potentialities, and the tremendous beauty of the land," she wrote in her foreward to Olga Racster's book (iii). She later spoke at the second conference on Native African Drama organised by the British Drama League in 1933 (Peterson 160).

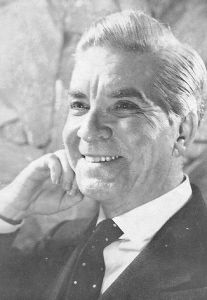

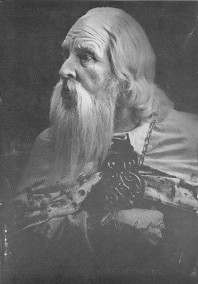

Meanwhile, Afrikaans theatre was taking off, despite the fact that the language itself was still finding its way. Gwen Ffrangçon-Davies put the matter succinctly: "The Afrikaans theatre has been forced into professionalism by the fact that there is no possibility of importing companies from overseas, and an indigenous theatre is the result" (11). The glamour of Leonard Rayne and his leading lady, Freda Godfrey - including their Shakespearean bent - were among the shaping influences on a stage-struck young man from Bloemfontein named Gerhardus Petrus Boorstlap, who became the noted actor André Huguenet. He attended every show that came to Bloemfontein, including Moscovitch's Merchant of Venice, which he saw four times (Huguenet 11). Huguenet earned his spurs in the various touring companies of the Hollander Paul De Groot (who gave him his stage name) and Hendrik Hanekom during the founding phase of Afrikaans theatre, but he was a man of wide theatrical sympathies. His younger colleague Johann Nel wrote of his "amazing capacity for hard work, his stern attention to detail, his burning desire to raise the standard of the Afrikaans drama, the artistry with which he is imbued . . ." (21). Huguenet's Hamlet, and especially his Lear, were among the roles that gave him his contemporary reputation as South Africa's foremost actor. His Lear premiered at the Port Elizabeth Opera House in 1960 in the production by Will Jamieson, to messages of support from acting friends Donald Wolfit, Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud (Attwell 59).

Gwen Ffrangçon-Davies and Marda Vanne

1940 saw the start of a war-time theatrical revival of sorts, initiated courageously by women, and heralded by the production in Pretoria by Gwen Ffrangçon-Davies and Marda Vanne of Twelfth Night, with the Afrikaans actress Lydia Lyndeque (then married to the poet Uys Krige, who was to translate Twelfth Night and King Lear into Afrikaans - see Kannemeyer 2002) playing Viola. Two other remarkable women, Margaret Inglis and Nan Munro, formed a second female-led semi-professional touring company in 1943, the Munro-Inglis company, though their purview inclined less to the classics than the Vanne/ Ffrangçon-Davies partnership. Marda Vanne (real name Margaretha "Scrappy" van Hulsteyn) was South African born. As a young girl, and in awe of Leonard Rayne, she one day wrapped herself firmly round a lamp-post outside the theatre during one of his performances and refused to let go until she had gained admission to the stage. Defying her parents, Sir Willem and Lady van Hulsteyn, she set her sights on a theatrical career. At one point she was married, briefly, to J.G. (Hans) Strijdom, later to become South Africa's fifth prime minister. In April 1940 she and Ffrangçon-Davies, who had met on the London stage, joined forces in South Africa to "perpetuate . . . the traditions of a faltering English stage [referring here to the devastation wreaked by the War], to bring something of genuine artistic interest to a culture-starved people" (quoted in Stopforth 212). Denied the West End, the two women unleashed their talents on the Union.

The success of the initial production led to the formation of a company, "The Good Companions," seventeen actors in all (not counting six support staff), who toured the Union first with Twelfth Night and Quality Street, doing one-night stands in small towns. Marda Vanne financed the venture herself. They travelled mostly by rail, and hired venues where possible from African Consolidated Theatres, whose cinemas played promotional slides in advance of the company's arrival. This alliance with cinema mogul I.W. Schlesinger was an important factor in resuscitating live theatre. Local repertory companies also helped them, and the company made a special effort to take theatre to (largely white) schoolchildren. They were a cosmopolitan group: four Afrikaners, an Irishman, a North Countryman, a Levantine, a few English-speaking South Africans, a Southern Englishman, a Welshman and two Zulus. The latter were two brothers, Zac and James Maccabeus. James had acted with André Huguenet's companies; Zac simply arrived one morning at rehearsal in Pretoria and told the company he was joining. [Note 5] Among the women was a young René Ahrenson, who was later to have a major impact on Shakespeare's fortunes in Cape Town.

The company made a small profit over the fifteen weeks, in which they played 44 towns, but more importantly the exercise had proven that round the country there was again a public for good theatre. They had their best houses in Durban, Pietermaritzburg, Grahamstown, King William's Town, and Oudtshoorn. They did well in Johannesburg, Pretoria, Robertson, Graaff-Reinet and Cradock. Support in Middleburg (Cape), Swellendam, Kroonstad and Cape Town was weaker. Shortly after the tour, Ffrangçon-Davies left to play Lady Macbeth in London opposite John Gielgud (they were life-long friends and colleagues -- see Croall 521), but she returned in 1943 and continued to work with Marde Vanne towards the ideal of a South African national theatre.

A South African National Theatre

This was a dream shared by André Huguenet and many others in theatre land. Both Ffrangçon-Davies and Huguenet wrote and lobbied tirelessly for the project, which inevitably became entangled in the drive for political dominance by resurgent Afrikaner Nationalism. The first concrete step was the consolidation of numerous amateur theatrical societies into a Federation, FATSA (die Federasie van Amateur Toneelvereenigings van Suidelike Afrika, to give its Afrikaans name), which grew out of the Krugersdorp Municipal Dramatic and Operatic Society under the leadership of P.P. "Breytie" Breytenbach. Some of the amateur theatrical societies of the day were lively, though they practiced the erratic eclecticism characteristic of such companies, and many were chary of Shakespeare for obvious reasons. Critics could be tough on amateur or semi-professional theatre. Denis Hatfield, a leading drama critic in Cape Town during this period, evidently didn't think much of Frank Hammerton's production of Othello for the Cape Town Repertory Theatre Society in December 1945: "I am unable to recall any Shakespearian production which so completely massacred the lines, murdered the poetry, and destroyed the tragedy as in this case" (Hatfield: 89). Contrast the same critic's ecstatic response to the Ffrangçon-Davies/Vanne production of The Merry Wives of Windsor at the Alhambra (another collaboration with African Consolidated Theatres) in May that same year: "Gwen Ffrançon-Davies [Mistress Page] skimmed the stage with her sails trimmed for any amount of preposterous action. What a superb actress she is! What charms, what conjurations, and what mighty magic of technique she carries in her armoury!" - and so forth (78).

The professionals wanted the material support that would allow them consistently to achieve professional standards, and also they wanted the status of official culture for their craft. Furthermore, the unfortunate practice of bringing accomplished international "leads" to tour - sometimes past their prime - and often supported by second-rate overseas companies, did little to advance the cause of indigenous South African theatre. [Note 6]"We should strive from the very outset," wrote Huguenet, "to encourage local art, our own painters, playwrights, actors, designers and technicians, and thus build a truly indigenous theatre" (1947: 93). Unfortunately their battle came at the very time that Afrikaner Nationalism was enforcing its stranglehold on political life and the fight for a national theatre became part of the struggle for the soul of the nation as conceived by white South Africans - a bitter contest fuelled by the legacy of the Anglo-Boer War and almost wholly neglectful of the African majority whose land this cultural enterprise was supposedly embracing. [Note 7]

The Board of Control met for the first time in July 1947. The Nationalists came to power the following year, and the political fog of apartheid closed in further. The inception of this misconceived bilingual English/Afrikaans "national" theatre was turbulent, with rival groups competing for national attention, important producers and actors defecting early on, complaints about bureaucratic rigidity, and a constant barrage of criticism, helpful and otherwise, in the periodical press. Major actors like Huguenet and Siegfried Mynhardt (he played a memorable Andrew Aguecheek in the 1953 National Theatre production of Twelfth Night, directed by Leonard Schach at Johannesburg's Reps Theatre) left the organization.

Notes

[5] Fresh from the experience of this tour, Lydia Lindeque wrote in her memoirs (1941):

Ek is ook bly dat ek die kans gehad het om te kan getuig van die mooi gees van camaraderie wat daar byna altyd onder toneelspelers heers, dit maak nie saak waar hulle hul bevind of wie of wat hulle is nie (8).

[I am also pleased to be able to testify to the fine spirit of camaraderie that almost always is among actors, no matter where they find themselves or who or what they are.] - trans. L.W.

"What" at the end of the sentence may refer to race, though it could also be merely a rhetorical flourish. [Back]

[6] Lydia Lindeque expressed some of the dissatisfaction she felt with imported English drama as follows:

Die teenswoordige Engelse "drama" is al baie uitgeput, ons het al genoeg gehad van hul spanning - of gril-stukke wat terselftyd nogal die pretensie het om sielkundige studies te wees - stukke wat wel 'n blasé West End-publiek 'n uur of drie lank kan verstrooi, maar hier by ons heeltemal uitheems is, met ons lewe niks te doen het nie, al speel die stuk hom ook af in'n luukse-hotel op die walle van die Vaal by vereeniging, al het al die karacters in die stuk die doodgewoonste Afrikaanse name en al duik hier en daar 'n enkele verdwaalde pittige boere-idioom tussen die "beskaafde" dialoog op . . ..

(162)

[Modern English drama has been pretty well exhausted, we have had quite enough of their thrillers and horror plays which at the same time pretentiously claim to be psychological studies, plays which might be able to distract a blasé West End public for three hours or so, but which are totally foreign to us here, have nothing to do with our life, even though the play takes place in a luxury hotel on the banks of the Vaal near Vereeniging, even if the characters have the most ordinary of Afrikaans names and even if here and there the occasional trenchant Afrikaans idiom crops up among all the "civilised" dialogue . . ..] - trans L.W.

Such feelings were not uncommon, and expressed the stirrings of nationalism, the pride of difference and the lingering trauma of the Anglo-Boer War. Scandanavian, American and German pieces seemed to her fresher and more appropriate. [Back]

[7] To help the reader gauge the bizarre racially-based amnesia that afflicted some of the better-intentioned people of the time, consider this passage from Stopforth's account of the genesis of the National Theatre, in which he summarises the views of the founding committee chaired by P.P.Breytenbach:

A National Theatre in South Africa would [be] one of the finest weapons against racialism. True art knows no race discrimination, and in a National Theatre Afrikaans actors and actresses would be cast in English plays, and English actors and actresses would be cast in Afrikaans plays when necessary. . . .. Such a National Theatre would be the pivot of a new cultural alliance between the two sections; it would knit the two races together, not only the artists, but audiences throughout the country.

(268-69)

The two "races" here are the white English-speakers and the white Afrikaans-speakers: no mention, no vague apprehension even, that others might conceivably be involved! This was no local vagary, but a deliberately inculcated perception reflecting a false view of political and social reality. [Back]